|

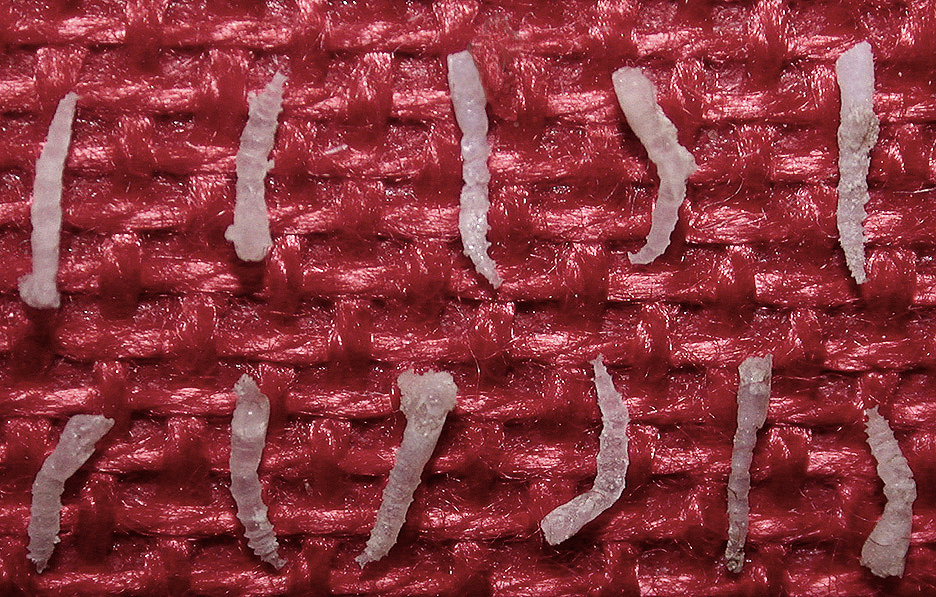

Here is a series of silicified--replaced by the mineral chalcedony (silicon dioxide)--midge pupae from the middle Miocene Barstow Formation, Mojave Desert, California. For perspective, the pupa at far right, in the upper row, is 4 millimeter long (about a sixth of an inch). Scientifically, it's called Dasyhelea australis antiqua. This particular species of midge, interestingly enough, is most closely related to the modern Dasyhelea australis australis, now living on the islands of Islas Juan Fernandez, about 400 miles west of Santiago, Chile. Adult midges of the genus Dasyhelea, by the way, while often referred to as "biting midges," do not actually suck the blood of animals. They thrive by ingesting the nectar from flowers. After dissolving the insects out of calcium carbonate (limestone) concretions with a diluted solution of formic acid, I photographed them with a Nikon CoolPix 995 digital camera in indirect lighting, with a flash unit. |