Click for weather forecast

| Visit a remote fossil locality near Yerington, Nevada, where some 35 species of ancient plant remains can be collected from the middle Miocene Aldrich Station Formation, approximately 13 to 12.5 million years old--including the leaves of evergreen live oak, winged seeds from spruce, and giant sequoia foliage. |

| The Field Trip | On-Site Images | Fossil Plants Images | Yerington Weather | The Fossil List | My Pages Email |

|

The Great Basin wilds of west-central Nevada are rich in productive fossil plant localities. While they are probably not as well known to amateur fossil plant hunters as the classic Paleocene through late Miocene (roughly 64 to 5.3 million years ago) leaf-bearing sites of Oregon, Idaho, Washington, Montana, Colorado and Wyoming, the Nevada fossil plant deposits continue to yield many excellently preserved paleobotanical remains. One of the more interesting and paleontologically rewarding leaf and seed-yielding areas lies near Yerington (the county seat of Lyon County) at Aldrich Hill. Here can be collected some 35 species of ancient plants from what geologists call the middle Miocene Aldrich Station Formation, a geologic rock unit dated at roughly 13 to 12.5 million years old. Among the many fossil plant remains found at Aldrich Hill are complete, carbonized leaves from an evergreen live oak, in addition to many conifer winged seeds and even giant sequoia foliage. It is indeed a special place to visit, an isolated region in the Great Basin "outback" where the Bureau of Land Management still permits the hobby collecting of fossil plant remains--a situation that could change literally overnight, by the way, should commercial collecting interests begin to raid the stratigraphic section, desecrating the integrity of the exposures and destroying in the process the great scientific value of the locality. Fortunately, Aldrich Hill remains accessible to the general public, and folks interested in collecting fossil plants there for personal use only may continue to visit, remembering of course that such specimens gathered must be neither sold nor bartered--activities which would constitute a clear violation of the rules and regulations established by the Bureau of Land Management for visitors to America's public lands. All of the fossil plants--including evergreen live oak leaves, spruce winged seeds, conifer needles, alder cones, and giant sequoia/big tree foliage--occur in the tan to reddish-brown and cream-colored diatomaceous to tuffaceous mudstones and shales of the middle Miocene Aldrich Station Formation exposed on the north side of Aldrich Hill. Excellent outcrops of the plant-bearing strata can be examined along the main wash which trends generally east-west across the northern side of Aldrich Hill. Additional productive fossiliferous exposures can also be found in the minor erosion gullies that dissect the north slope of the hill. It should also be pointed out that virtually every outcrop of diatomaceous mudstones and shales in the Aldrich Hill district yields fossil plant material in varying degrees of relative abundance, from very rare to common, although the prominent and accessible exposures along the north side of the hill have in a historical sense provided collectors with the majority of paleobotanical remains. When fossil hunting at Aldrich Hill, as at most other fossil leaf and seed-yielding localities, try to cover as much terrain as possible in search of the most productive layers. Split heaps of the shales with the blunt end of a geology hammer whenever you stop for a "look-see." Some folks prefer to use the pick end, obviously, of a geology rock hammer, though this technique actually decreases the likelihood of splitting with precision the blocky diatomaceous mudstones and shales; too, a number of collectors prefer a roofer's or brick-layer's-style hammer, with a wide narrow blade, which theoretically splits shales with great effectiveness. Such a hammer probably works well with very soft, classically fissile shales, but the tool lacks any kind of "punch," or heft, for cleaving bulkier, more compacted mudstones and shales. The upshot: the blunt end of a traditional geology hammer splits the Aldrich Station Formation diatomaceous shales and mudstones quite nicely. Remember, of course, to wear safety goggles, or some manner of eye protection while splitting the mudstones and shales. Although nowhere abundant, the fossil plant impressions in the Aldrich Station Formation are nevertheless common and even obvious at several horizons in the diatomaceous material. Watch for their pale to dark-brown, carbonized coloration on the tan to reddish-brown and cream-colored rocks. Associated with the leaves, winged seeds, and twigs are conspicuous oval specimens roughly one-half to one inch in diameter. These fossils represent the internal molds of fresh water clam shells; the actual shell substance has long since been dissolved away, as the siliceous mudstones and shales were evidently a poor medium of preservation for the tests of pelecypods. If a microscope is available, you can, in addition to finding the plants and clams, examine the remains of an especially prolific fossil type at Aldrich Hill--the diatom. This is a microscopic photosynthesizing single-celled alagae which during the geologic past, particularly in west-central Nevada in rocks of middle through late Miocene age (roughly 17 to 5 million years ago), contributed its resistant siliceous remains in vast numbers to the plethora of paleohistory in the rocks. The scientific extraction of diatoms for paleobotanical study is a dangerous operation, involving as it does the use of several powerful acids, among them hydrochloric, sulfuric and hydrofluoric--potent brews that if not handled properly can cause frightful, life-threatening burns. It is a process only an expert should attempt. Fortunately, though, you can get an adequate, general view of diatoms simply by powdering a small amount of diatomaceous matrix on a glass microscope slide and then examining the residues under moderate to high powers of magnification. Most of the diatoms from the Aldrich Hill district resemble minute boxcars and discs. Excluding the numerous species of diatoms identified from the Aldrich Station Formation, some 35 species of fossil plants have been described from the exposures at Aldrich Hill--a fossil deposit first investigated scientifically in the early 1940s by the late paleobotanist Daniel I. Axelrod during one of his geological reconnaissance investigations in Nevada. Axelrod eventually published his paleobotanical, paleoecological, and geological conclusions concerning the Adrich Hill paleoflora in a monumental paleobotanical monograph, where he additionally describes in detailed scientific fashion three more important Nevada fossil floras (Middlegate Formation, Chloropagus Formation, and Desert Peak Formation). All of the fossils from Aldrich Hill occur in the Aldrich Station Formation, as named by Axelrod in his treatise, a geologic rock unit originally considered transitional Miocene-Pliocene (about 10 million years old by the geologic time scale then in fashion--as recalibrated, the Miocene-Pliocene is now established at roughly 5.3 million years ago), but now considered middle Miocene in geologic, or approximately 13 to 12.5 million years old. The Aldrich Station paleoflora shows quite a variety in its composition. The five most commonly collected specimens are, in decreasing order of relative abundance: (1) winged seeds from three varieties of spruce--Picea sonomensis (by far the most abundant representative of the paleoflora), whose seeds appear identical to the modern Brewer Spruce (Picea breweriana) of the Klamath region of northwestern California and adjacent Oregon; an extinct spruce that Axelrod called Picea lahontense--a conifer whose seeds cannot be compared with any known living spruce, although they do show a general similarity to those produced by a few modern "larger-coned" spruces of eastern Asia, chiefly China; and a presumed extinct spruce called Picea magna, whose winged seeds resemble those produced by the living tiger-tail spruce, Picea polita, a conifer now native to the volcanic soils of Japan; (2) fragmental and occasional complete, intact leaves from an evergreen live oak called Quercus pollardiana, a species that is practically identical to the modern maul oak, also called canyon live oak, Quercus chrysolepis, presently native to the moist western slopes of the Sierra Nevada and the Coastal Ranges of California; (3) leaves from a species of cottonwood, Populus payettensis, whose fossil foliage matches leaves produced by the living Narrowleaf Cottonwood, Populus augustifolia; (4) foliage/twigs of giant sequoia, Sequoidendron chaneyi, that match very well with those produced by the living Sierra Redwood/Big Tree, Sequoiadendron giganteum, which is now restricted solely in natural habitat to a narrow, moist belt along the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada in California; and (5) leaves from a species of willow referred to as Salix payettensis--its foliage appears very similar, if not identical to leaves produced by the modern willow Salix exigua, a rather widespread variety that goes by many common names, such as Coyote Willow, sandbar willow, or even Narrowleaf willow. The nine next most-common specimens encountered are: Catalina ironwood, Mountain alder, an extinct water oak, California buckeye, black cottonwood, an extinct cottonwood, zelkova, Arizona ash, and Cedar elm. Rarer occurrences include such varieties as sugar pine, white fir, Ponderosa pine, Douglas-fir, Western Red Cedar, Western hemlock, California sycamore, serviceberry, Oregon grape, California coffeeberry, coralberry, japanese pagodatree, birch-leaf mountain mahogany, and a Horsetail. The vast majority of fossil plants recovered from the middle Miocene Aldrich Station Formation at Aldrich Hill show a demonstrable resemblance to their modern analogs still living today. For example, the humid cooler-weather conifer elements in the paleoflora (spruce, fir, pine, giant sequoia) have their closest contemporary counterparts in the Sierra Nevada and Cascade Mountains regions of western North America. As a matter of fact, there is a direct relationship postulated between the overall composition of the Aldrich Hill Miocene flora and modernday plant associations present in the giant sequoia forests of the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada in California--specifically, the spectacular Sierra Redwood groves at Calaveras Big Trees State Park and Sequoia National Park. Based on the known climatic requirements of present day plant counterparts of the fossil flora, the Aldrich Hill district some 13 to 12.5 million years ago had quite a different environment than the arid juniper-sage-Pinyon pine associations observed there today. For one thing, rainfall was approximately 25 to 30 inches per year, distributed in both winter and summer months. This is fully 15 inches more than the area receives today, with almost all of the effective precipitation now occurring during wintertime as snow and rain. Temperatures today also show much greater extremes than what can be inferred for the moderate middle Miocene days, when freezing conditions were extremely rare and summer highs normally ranged around 85 degrees. This contrasts dramatically with today's regular winter weather patterns that mimic Arctic-style extremes and summer peaks to over 100 degrees Fahrenheit. Elevations at the sites of deposition were in all likelihood slightly higher than the 6,000 to 6,700 feet we observe today in the Aldrich Hill district--probably an elevation between 7,000 and 7,500 feet for those middle Miocene times is not out of the question. In addition to telling us something of the climate of the geologic past, the Aldrich Hill fossil plant bonanza also reveals a striking gradual change in both the local paleogeography and the associated plant communities. In the earliest phases of their deposition, the fossil plants reveal that the ancestral Aldrich Hill region was a broad valley within which sprawled one or more fresh water lakes of perhaps moderate to large size; the diatoms preserved in the Aldrich Station Formation suggest that the lakes were rather cool and deep and well within the range of normal mineral content. Occasionally, though, volcanic activity from distant areas contributed layers of ash and pumice to the accumulating diatomaceous sediments. The adjacent slopes supported a thick mixed conifer forest consisting of white fir, Ponderosa pine, Brewer spruce, Douglas-fir, Western Red Cedar, Western hemlock and giant sequoia, along with a subordinate deciduous grouping of alder, poplar, cottonwood, willow, elm, zelkova, japanese pagodatree, and coralberry. Living on the more exposed slopes were evergreen live oak, serviceberry, California buckeye, cottonwood and ash. Yet, higher in the geologic section at Aldrich Hill, in rocks younger by hundreds of thousands of years, the fossil plants prove that the geography had changed significantly. In place of a widespread conifer forest with only minor areas of woodlands surrounding a great lake basin, there had developed a vast hilly woodland where only a few interfingers of forest penetrated from the higher slopes surrounding the lake basin of deposition. Replacing big tree, spruce, pine and other conifers as dominants were evergreen live oak, mock locust, California buckeye, coralberry, mountain mahogany and serviceberry--a paleoenvironment that was much more xeric in nature than that suggested by plant communities which had preceded it. Here rare forest elements were white fir, Ponderosa pine, western hemlock and giant sequoia. Also present in the forest association were such species as alder, hollygrape, Catalina ironwood, cottonwood, poplar, elm, willow and zelkova. The once thriving forest grouping of conifers and deciduous varieties appears to have survived in the upland regions, descending into the dominant evergreen live oak territory only under especially favorable conditions. Today, the sedimentary rocks at Aldrich Hill provide proof that roughly 13 to 12.5 million years ago an extensive giant sequoia forest reigned over what is presently an arid Great Basin land of sage and juniper and Pinyon pine. Along with the big trees grew such plant varieties as Brewer spruce, Ponderosa pine, white fir, Western hemlock, evergreen live oak, and an array of deciduous kinds--a scene that closely resembles the modernday humid western slopes of California's Sierra Nevada in the vicinity of Calaveras Big Trees State Park east of Angels Camp, where two groves of mighty Sierra Redwood continue to thrive in a setting of pristine grandeur. Within the diatomaceous mudstones and shales of the middle Miocene Aldrich Station Formation can be found direct evidence of that ancient Big Tree forest, the beautifully preserved carbonized impressions of plant remains covered over by the sediments in a long-vanished lake--leaves and seeds and conifer foliage which only await a patient, dedicated fossil hunter to bring to their first light of day in many millions of years. |

|

|

|

Click on the imagae for a larger picture. Left--Here is the view near Aldrich Hill, Nevada, looking essentially due north across the fossiliferous diatomaceous mudstones and shales of the 13 to 12.5-million-year-old middle Miocene Aldrich Station Formation (foreground and the hill at upper right), which yields 35 species of ancient plants. Right--Looking northeastward from the western side of Aldrich Hill. Exposures of whitish sedimentary rocks in the foreground and in the distance belong to the fossil plant-bearing middle Miocene Aldrich Station Formation. |

|

|

|

|

Click on the images for a larger pictures. Left--Collectors inspect a narrow erosion gully along the north side of Aldrich Hill, Nevada, for fossil plant remains in the middle Miocene Aldrich Station Formation; the view is roughly due west. Middle--A collector gets down to business at an outcrop of the middle Miocene Aldrich Station Formation along the north side of Aldrich Hill, Nevada. The regularly bedded, tan to reddish brown and cream-colored diatomaceous mudstones and shales here yield infrequent to rather common 13 to 12.5-million-year-old carbonized impressions of conifer winged seeds and giant sequoia foliage, in addition to evergreen live oaks and many deciduous varieties. Right--A collector searches for fossil plant remains in the middle Miocene Aldrich Station Formation in an erosion gully along the north side of Aldrich Hill, Nevada. The view is roughly due west. |

|

|

|

|

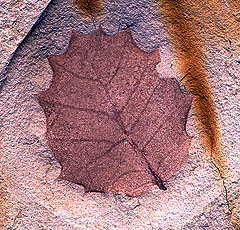

Click on the images for a larger pictures. Left--Here is a complete spinose leaf from an evergreen live oak Quercus pollardiana, collected from the middle Miocene Aldrich Station Formation at Aldrich Hill, Nevada. It is practically identical to leaves produced by the modern maul oak, also called canyon live oak, now native to the western Sierra Nevada and the Coastal Ranges of California. The specimen is 30mm long. Middle--A complete leaf from an evergreen live oak called Quercus pollardiana from the middle Miocene Aldrich Station Formation, Aldrich Hill, Nevada. This particular species of fossil oak is allied with the modern maul oak, Quercus chrysolepis, which is presently native to the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada and the Coastal Ranges of California; note the entire margin (smooth, without spinose indentations) of the fossil leaf. Modern maul oaks can produce on the same tree leaves that are entire and others that are spinose. The specimen is 35mm long. Right--Two fossil alder cones (the twig-like specimen at the bottom of the image is an unidentified plant fragment) from the middle Miocene Aldrich Station Formation, Nevada; left to right, cones are 21mm 18mm long, respectively. They came from a species of alder called Alnus smithiana, which is similar to the modern Alnus tenuifolia, or the Western American Alder--sometimes called the Mountain Alder. |

|

|

|

|

Click on the images for a larger pictures. Left--This is a leaf fragment from Lyonothamnus parvifolius, the fossil equivalent of the modern Catalina ironwood (Lyonothamnus floribundus) and channel ironwood (Lyonothamnus asplenifolius)--also called Lyon Tree, both now restricted in native habitat solely to the Channel Islands off the coast of Southern California. The specimen is roughly 25mm in actual length and was collected from the middle Miocene Aldrich Station Formation, Nevada. Middle--A twig from a giant sequoia (Big Tree, called Sequoiadendron chaneyi), measuring 26mm in length, collected from the middle Miocene Aldrich Station Formation, Aldrich Hill, Nevada. It is approximately 13 to 12.5 million years old. Right--For comparison with the specimen of fossil Big Tree foliage in middle, here is a Big Tree twig plucked from the giant sequoia (Sequoidendron giganteum) we have planted in our back lot; the specimen shown here is 65mm in actual length. Note the distinctive awl-shaped leaves, which also show up well in the fossil specimen in middle. |

|

|

|

|

| Click on the images above for larger pictures. Here are four fossil winged seeds from a spruce; all were collected from the middle Miocene Aldrich Station Formation at Aldrich Hill, Nevada. Carbonized impressions of spruce seeds are among the most common fossil plant remains found at Aldrich Hill, but they are maddeningly difficult to identify to a species level. At the upper left is a winged seed that appears to match what the late paleobotanist Daniel I. Axelrod called Picea sonomensis, whose winged seeds are similar to the modern Brewer Spruce (also called the weeping spruce), Picea breweriana, a rather rare variety whose native habitat is now restricted to the Klamath region of northwestern California and adjacent Oregon. The winged seed remains shown at upper right and lower left most closely resemble conifer seed specimens Axelrod called Picea lahontense, which is an extinct species that cannot be compared directly with any living spruce. According to Axelrod, it seems to bear a closest affinity with the larger-coned spruces of eastern Asia, chiefly China, although P. lahontense is most certainly extinct. At the lower right is a winged seed that closely resembles what Dr Axelrod called Picea magna, a variety of extinct spruce whose winged seeds show a general relationship to the living Picea polita, the tiger-tail spruce now native to the volcanic soils of Japan. The specimens at top left and right are, respectively, 12mm and 17mm long; those at bottom left and right are, respectively, 14mm and 15mm in length. |

|