| Text: The Field Trip | Images: On-Site | Images: Fossil Live Oaks |

| Images: Fossil Oaks | Images: Fossil Spruce-Fir | Links: My Music Pages |

| Links: My Fossils Pages | Links: Online USGS Papers | E-Mail Address |

|

Perhaps the richest producer of Miocene-age (23-to-5.3-million-year-old) plants in the entire state of Nevada is a geologic rock deposit known as the Middlegate Formation. Its primary and most paleontologically productive exposures lie within a rather localized geographic area of west-central Nevada, where paleobotanists have identified some 64 species of fossil plants--including such diverse types as evergreen live oak, giant sequoia/Big Tree, willow, fir, maple, and spruce. The fossil specimens, which consist of leaves, winged seeds (called samaras in technical botanical terminology), acorn cups, seed pods and branchlets, occur as pale to dark brown carbonized impressions on a cream-white to pale-brownish matrix of opaline shale--many of them exhibiting such an exceptional degree of preservation that the original delicate venation on the leaves is clearly visible. All of the remains are middle Miocene in geologic age, dated by radiometric methods at some 16 million years old. They occur in the uppermost (the youngest layers of deposition) 30 feet of the Middlegate Formation, just below the overlying Middle Miocene Monarch Mill Formation, whose basal sedimentary conglomerates have yielded to paleontologists a large vertebrate fauna, including the silicified bones of moles, rabbits, squirrels, beavers, mountain beavers, mice, weasels, martins, rhinocetotids, oreodonts, camels, llamas, and pronghorns. Such scientifically invaluable fossil vertebrate material on Public Lands is of course off limits to all collectors who do not possess a special use permit issued by the Bureau of Land Management, a permit issued solely to individuals with a minimum B.S. degree from an accredited university whose research projects can be verified as authentic by the petitioned authorities--a formal collecting status that is likely well understood (and appreciated) by most amateurs and professional paleontologists alike. At present, though, there is no such legal restriction on the hobby gathering of leaves, winged seeds, petrified wood, and other paleobotanical remains from the Middlegate Formation--but that much-welcomed legally lenient status could of course change without advance warming. The troubling circumstance is that, recently, commercial collecting interests have begun to concentrate on a select number of fossil leaf-yielding fields in Nevada--obviously those sites which happen to provide them with the greatest numbers of well-preserved specimens. Needless to report, this is patent illegal activity, since no fossil remains collected on Public Lands may be either sold or bartered (legal argot for the act of trading specimens). And while there is certainly nothing criminal about selling fossil specimens collected on private lands (with the land owner's unambiguous permission, of course), any desecration of a fossil horizon on Public Lands in an attempt to secure as many saleable remains as possible is without question an offense punishable by law. Also, such behavior is with sure consequence horribly counterproductive, since it only invites federal officials with the Bureau of Land Management and the Forest Service to close down popular fossil areas, preventing conscientious amateurs from sampling places of significant paleontological interest. The Middlegate Formation locality certainly fits that description. It's a remarkably productive fossil plant-yielding region situated in the middle of the Great Basin Desert, amid what botanists call a shadscale desert flora, or an association of low, rigid, spinescent shrubs no more than two feet high. But 16 million years ago the Middlegate Formation district was the site of a deep, cool, clear-water lake, a great body of water into which creeks and streams occasionally discharged loads of fine detritus, along with abundant plant debris from the surrounding countryside--a landscape rich with conifers, deciduous varieties and evergreen live oaks which now lie preserved along the bedding planes of fine-grained shales. The most efficient way to locate fossil plants in the Middlegate Formation is to dig into the slabby-weathering siliceous shales, exposing fresh sedimentary strata below the surface. Fortunately, most of the shales within a few inches of the surface are severely fractured; hence, little splitting of them is necessary, since they tend to separate from the outcrops in thin sheet-like plates. Watch closely for the fossil plant compressions and impressions along the bedding planes of every shale fragment you remove from the hillside exposures. The deeper you dig, though, the more thickly bedded the opaline shales become, until at last it will become necessary to begin splitting the extremely dense, concrete-like rocks. When doing this, always remember to wear safety goggles, or at least some kind of eye protection such as sunglasses. The denser, thick-bedded opaline strata crack apart only with the greatest of applied brute force, thus increasing the likelihood that sharp fragments might launch off the matrix into your eyes. Stand slabs of shale on end, then give them a sure whack with the blunt end of a geology hammer. If you're fortunate, the sedimentary layers will break apart along their original planes of deposition, revealing perfect carbonized leaf and seed impressions and compressions to their first light of day in approximately 16 million years. By far, the most common specimens found in the Middlegate Formation are leaves and acorn cups belonging to an evergreen live oak, Quercus pollardiana, which is identical to the modern canyon live oak native to the western flanks of the Sierra Nevada and the coastal ranges of central California. The 18 next most frequently encountered remains in the Middlegate shales include: interior live oak (leaves); Birchleaf mountain-mahogany (leaves); tanbark oak (leaves); common cattail (leaves); Bigleaf maple (leaves and samaras); Balsam poplar (leaves); willow (leaves); Boxelder (samaras and leaflets); Brewer spruce (samaras); Tigertail spruce (samaras); silver maple (samaras and leaves); Arizona madrone (leaves); Catalina ironwood (leaves); Giant Sequoia (branchlets); New Mexican locust (leaflets and seed pods); California Red fir (samaras and needles); small-stemmed Horsetail (stems); and Ponderosa Pine (samaras and needles). Twenty of the rarest species reported from the Middlegate Formation include: Golden Chinkapin (a brush-sized variety--leaves); Paper birch (leaves); Hairy mountain-mahogany (leaves); quaking aspen (leaves); Utah juniper (branchlets); an extinct water oak (leaves); Narrowleaf cottonwood (leaves); a second species of willow (leaves); White ash (samaras); Oregon grape (leaves); Alaskan cedar (branchlets); water lily (leaves and rootstocks); Rocky Mountain hawthorn (leaves); Rocky Mountain maple (samaras and leaves); Douglas-fir (samaras); Mountain hemlock (samaras); Golden chinkapin (tree variety--leaves); East Asian maple (samaras and leaves); and Cedrella (samaras). The Middlegate fossil flora was discovered in the Spring of 1949 by Laura Mills, an avid amateur fossil collector from Fallon who at the time was searching for petrified wood. She brought the rich fossil deposit to the attention of paleobotanist Daniel I. Axelrod, who accompanied her to the locality in the early summer of 1949. Several weeks later Axelrod made his first substantial collection of plants from the Middlegate Formation--a fantastic array of Miocene species preserved in superior detail; here was certainly one of the most productive and important fossil plant localities in all the Great Basin. Two years later, during the Spring of 1951, Axelrod made yet another visit to Middlegate, this time accompanied by his long-time field assistant Robert E. Smith, who maintained accurate records of the various plant taxa recovered from the shales. They spent an entire week in the field, eventually amassing a truly exhaustive selection of Miocene fossil plant material. In all, Axelrod and Smith gathered some 3,458 specimens from the Middlegate Formation, 2,917 of which belonged to the evergreen live oak Quercus hannibalii. Axelrod published his scientific examination of the Middlegate plant material in 1956 in a formal scientific paper. In it, he described 42 specimens of ancient plants, assigning them a transitional Miocene-Pliocene geologic age, or what was then understood to be roughly 12 to 10 million years old. Axelrod later revised the Middlegate fossil plant association in another formal paleobotanical publication. He based this new scientific analysis on supplemental collections of fossil plants supplied by Axelrod's students in paleobotany at the University of California, Davis, during the 1970s. The student collecting expeditions not only increased the total number of specimens known from the Middlegate Formation to 6,882, but also added some 22 new species of fossil plants to the ever-expanding paleobotanical record. In addition to the larger plant collections, Axelrod also had at his disposal increasingly sophisticated and accurate radiometric methods of dating volcanic rocks interbedded in a sedimentary sequence. In the late 1960s, geologist Harold Bonham of the Nevada Bureau of Mines And Geology selected fresh samples from hornblende rhyolite tuffs present near the middle of the Middlegate Formation. When Bonham ran the volcanics through a series of radiometric-age analyses, paleobotanists were shocked to learn that the fossil plants could not be transitional Miocene-Pliocene as originally determined (12 to 10 million years old, prior to the recalibration of both the Miocene and Pliocene Epochs; for example, the Pliocene now begins at about 5.3 million years ago), but rather more in the range of 18.5 million years old, or middle Miocene in geologic age. More recent radiometric determinations, though, prove that the Middlegate Formation is younger still--more in the range of 16 million years ancient. In his monographs dealing with fossil plants from Nevada, paleobotanist Daniel I. Axelrod concluded that the Middlegate Flora most closely resembles a modern sclerophyll forest, which reaches its ultimate development in the western Sierra Nevada and the coastal ranges of central California. Such a forest is dominated by evergreen dicotyledons, principally madrone, Golden chinkapin, tanbark oak and several specimens of oak; typical evergreen shrubs include buckbrush, mountain mahogany, toyon, sumac, and manzanita--all of which contribute to a classical chaparral botanic association. In addition to the evergreen species, a typical sclerophyll forest can also include such deciduous types as maple, ash, black walnut, sycamore, cottonwood, currant, rose and willow, each of which prefers the moister sites around streams and seepages. The association of sclerophyllous species found in the Middlegate Formation suggested to Axelrod that the fossil plants lived under environmental conditions quite similar to those present today in the Santa Cruz and Santa Lucia Mountains along the coast of central California. There are also obvious relationships to the modern groves of Giant Sequoia in both the northern and southern portions of the Sierra Nevada, particularly the North Grove (southeast of Auburn) in Placer County and the Tule River Grove near Belknap Creek in Tulare County. Based on the available geological evidence, the fossil plants accumulated in waters of moderate depth roughly one-half mile from the southern margin of the Miocene Lake, into which creeks and streams discharged detritus from south-facing slopes of volcanic origin during periods of intermittent storm runoff. Surrounding the basin of deposition and reaching down to lake level was a dominantly sclerophyllous forest consisting of madrone, Golden chinkapin, tanbark oak, canyon live oak, interior live oak, and water oak. Drier sites in the ancestral Middlegate Basin supported such shrubs as buckbrush, mountain-mahogany, toyon, Lyontree, and locust. The stream banks were lined with species of maple, cottonwood and willow, while higher elevations along the distant slopes supported an impoverished conifer-hardwood forest of fir, spruce, pine, Alaska-cedar, Douglas-fir, and Giant Sequoia. Associated with the conifers were such deciduous varieties as alder, maple, hawthorn, willow, and mountain ash. Summer rain indicators in the Middlegate Flora include types whose closest modern relatives live in the eastern United States, eastern Asia, and the southern Rocky Mountains--such deciduous species as birch, persimmon, hawthorn, hydrangea, Oregon grape, maple, and cottonwood. All of these varieties prove that throughout Middle Miocene times there must have been, at a minimum, some two to three inches of precipitation during each of the three summer months; this contrasts wildly with the extreme aridity of the Middlegate Formation territory today, which receives on average only 5 inches of rain per year. Yet, 16 million years ago the Middlegate Basin received approximately 35 to 40 inches of rain on an annual basis, an estimate based on the known environmental requirements of living members of the fossil flora. The middle Miocene Middlegate climate can be categorized as mild-temperate, with an average temperature reading for the month of January of 40 degrees; today temperatures there remain below freezing throughout January, averaging a chilly 30 degrees. Summertime weather conditions were also more moderate during middle Miocene times, when typically an entire month of July averaged fully 10 degrees lower than that experienced in the area today--68 degrees for the Miocene, compared with 78 in the present-day. Elevations at the site of deposition were likely much higher than today's 5,000 to 5,300 feet--more in the neighborhood of 8,000 feet. This estimate is based on rather recent sophisticated geophysical and paleobotanical studies which demonstrate that 16 million years ago the ancestral Great Basin region stood appreciably higher than it does at present; by 6.8 million years ago, elevations had collapsed through extensional geologic stresses to roughly the same as what we see today in the Great Basin. Here is certainly one of the premiere fossil localities in all of Nevada: the Middlegate Formation, a place where professional paleobotanists and amateur fossil enthusiasts alike have recovered through a period of several decades thousands upon thousands of well-preserved leaves, seeds, acorn cups, seed pods, conifer needles, and branchlets. Today, the site lies within the brutal aridity of a shadscale desert, a land of low spiny shrubs adapted to harsh alkaline soils, great extremes in temperatures, and scant rainfall--as low as 5 inches per year. It's a scene radically different from the one which existed throughout this portion of the Great Basin some 16 million years ago, when vegetation identical to that now living near the Giant Sequoia groves in the western Sierra Nevada and in the coastal ranges of central California thrived in a moist land of ample rainfall--where a great pristine lake splashed the trunks of canyon live oak and Giant Sequoia. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Here are two views of the famous Middlegate Formation fossil flora locality. At left is a photograph taken from a distance of about two miles from the Middlegate Formation, which is composed of lacustrine (lake-deposited) cream-white to pale-brownish opaline shales, within which a genuine bonanza of beautifully preserved fossil leaves, seeds, and branchlets can be found. At right is an image of the prime fossil plant-bearing site in the midst of the Middlegate Formation; here, the rounded hills composed of siliceous opaline shales produce some 64 species of ancient plants from the middle Miocene epoch, roughly 16 million years old. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right--Parked in the wash which leads to the middle Miocene Middlegate Formation fossil locality, proper. Preparing to park along right edge of wash. Low hills at right distance must be hiked over to locate best exposures of the cream to whitish fossiliferous opaline shales, a representative outcrop of which can be seen just to the right of jeep. Right--An explorer of middle Miocene times "assumes the paleobotanical position"--nose to the ground, seeking with deliberate diligence the wonderfully preserved fossil leaves, seeds, acorn cups, and branchletts in the middle Miocene Middlegate Formation, some 16 million years ancient. |

|

|

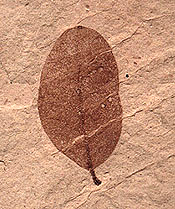

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Here are two 16-million-year-old fossil evergreen live oak leaves from the middle Miocene Middlegate Formation, a classic fossil leaf and seed locality situated in the Great Basin Deser; both specimens are complete leaves from Quercus pollardiana, a species of evergreen live oak that is identical to the living canyon live oak now native to the western foothills of the Sierra Nevada and the coastal mountain ranges of central California. The specimen at left is 45 millimeters long; leaf at right is 35mm in length. The Middlegate Formation fossil flora yields some 64 species of ancient Middle Miocene plants roughly 16 million years old. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Fossil leaves from the middle Miocene Middlegate Formation, Nevada. At left is a complete leaf specimen from the extinct water oak, Quercus simulata, 50 millimeters in length; at right is an essentially complete leaf (stem is partially obscured by opaline shale matrix) from a tanbark oak, Lithocarpus nevadensis, which is 65mm long. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Here are two fossil conifer winged seed (samaras in botanical terminology) from the middle Miocene Middlegate Formation, Nevada: Specimen at left is a seed from the Miocene species of Brewer spruce (now native to the Klamath Mountains of northwestern California), Picea sonomensis, 15mm long; at right is a seed from the Miocene variety of California Red fir, Abies laticarpus, which is 30mm in length. |

|