| Text: Introduction | Text: BLM Rules | Text: The Field Trip |

| Images: On-Site | Images: Fossils | Links: My Music |

| Links: My Fossils Pages | Links: USGS Papers | Email Address |

|

|

|

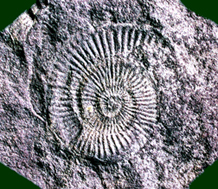

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: (1) A complete ammonite (an extinct order of cephalopod), called scientifically Psiloceras pacificum from the lower Jurassic Sunrise Formation, Ammonite Canyon, Nevada. It is from the Hettangian Stage of the early Jurassic, around 198 million years old. (2) An explorer of the Mesozoic Era searches for paleontological specimens in the lower Jurassic beds of the upper Triassic-lower Jurassic Gabbs Formation, Ammonite Canyon, Nevada; strata here were deposited during the Hettangian Stage of the Jurassic Period, approximately 199 to 196 million years ago; Many species of ammonites, along with solitary corals, brachiopods, gastropods, and pelecypods--plus, such microfossils as radiolarians, foraminifers, ostracodes (a minute bivalved crustacean), microgastropods, micropelecypods, and even the last known conodonts in the geologic record (conodont denticles of latest Triassic geologic age--that is, a minute tooth-like food gathering calcium phosphate apparatus unrelated to modern jaws)--can be found in late Triassic through early Jurassic strata exposed throughout the canyon's corridor. |

|

All Ammonite Canyon localities presently reside on BLM-administered territory (United States Bureau of Land Management)--a conservation category also commonly called Public Lands. This is a long-held, well-understood American legal status that affords unauthorized amateur paleontology enthusiasts an opportunity/privilege to collect within the confines of Ammonite Canyon reasonable amounts of common invertebrate fossils, without first securing from the BLM a customary special use permit. Without that permit, vertebrate remains encountered on Public Lands must be left where found (taking photographs of vertebrate fossils is not yet illegal, though). Unfortunately, that special land status could literally change overnight, without any degree of advance warning. The undeniable scientific fact of the matter is, Ammonite Canyon remains a world-famous fossil-producing region that hosts perhaps the most complete late Triassic through early Jurassic--approximately 205 through 195 million years ago--ammonite succession in the world; that is, paleontologically significant species of ammonoids (Triassic types) and ammonites (Jurassic and Cretaceous) are stacked directly atop one another in distinct layers--called "zones" by stratigraphers--just as they were deposited through roughly 10 million years of sedimentary accumulation. Too, the rich, inclusive Mesozoic Era cephalopod assemblage is exceptionally well exposed in a stark Great Basin Desert setting--no vegetation covers the ancient strata--permitting accessible opportunities to study in great scientific detail one of our planet's major mass extinction of plants and animals--the paleobiologically traumatic Triassic-Jurassic boundary extinction of roughly 202 to 198 million years ago. Indeed, not a few professional paleontologists consider the area worthy of a World Heritage designation. Probably that most restrictive of strictures is not likely to come to pass anytime soon--if at all, actually. On the other hand...the BLM could at any arbitrary moment decide to place Ammonite Canyon into a special conservation category called an Area Of Critical Environmental Concern (ACEC, for short). And make no mistake about it: This will most certainly happen should commercial collecting interests begin to desecrate through illegal mechanized gathering of fossil specimens the priceless stratigraphic integrity of the Mesozoic Era geologic section. Also, if ammonites and other invertebrates from Ammonite Canyon begin to appear for sale with egregious frequency via the Internet, or at various rock, gem, and fossil shows around the United States--and world for that matter--the Bureau of Land Management will then, with obvious legal precedent, have reasonable justification to close Ammonite Canyon to all but trained, professional paleontologists. This is because, according to the laws regarding fossil collecting, paleontological specimens gathered on Public Lands shall neither be sold, nor bartered (in legal argot, generally understood to mean traded); such specimens are intended solely for personal hobby use only. By the way, a noted fossil-bearing Area Of Critical Environmental Concern already administered by the BLM is the Upper Pleistocene Manix Lake Beds, Mojave Desert, California, where significant Ice Age remains of fish, mammals, birds, and mollusks occur; fossil collecting is illegal there without a special use permit, which is given solely to individuals with a minimum B.S. degree from an accredited university (or to qualified members of respected, established museums) who seek to undertake fully valid research investigations that can be verified as authentic by the petitioned authorities. The upshot here is pretty much this: Should a clear pattern of collecting abuse develop, Ammonite Canyon, because of its abundant association of marine invertebrate fossils that span the important Triassic-Jurassic Period extinction boundary--it is, indeed, one of the best exposed and most reliably fossiliferous localities on Earth in which to study the traumatic end-time Triassic mass extinction and eventual recovery of paleo-ecosystems during the succeeding Jurassic Period--will most certainly be closed to all unauthorized amateur paleontology enthusiasts. |

| Visit my verbatim transcriptions of the informative Bureau of Land Management (BLM) online brochures, Fossils On America's Public Lands and Collecting On Public Lands for rules and regulations regarding the collection of fossil specimens and other resources on Public Lands. |

|

Several years ago, during my first trip to Buffalo Canyon, Nevada--a locality that yields abundant and well-preserved Middle Miocene leaves and seeds some 15 million years old--I happened to learn of a tremendous Triassic-Jurassic Period, Mesozoic Era fossil-bearing area in the Great Basin Desert of Nevada. It's often strange how such things come about. I was camped along the dirt access path, in the heart of the fossil plant-yielding district, when a four-wheel-drive vehicle came bounding around the bend in the distance; it was approaching fast, churning up billows of dust. While camped in isolation there in Buffalo Canyon, I had not seen another human being in three days and nights, so naturally I was surprised to encounter another explorer of the sparsely populated Basin And Range outback. It came to pass that that individual maneuvering his vehicle across the terrain was a field geologist employed by a local gold exploration company. He'd been sitting "on top of a rich strike" for some five days, taking core samples and assessing the mineral potential of the find--a huge gold field in which the precious metal was disseminated through the country rock in microscopic particles. He even showed me a typical sample of the ore, an improbable-looking bluish-gray mud through which, I was soberly assured, the gold was liberally distributed. I had to take his word for it, of course, since there was obviously no distinctive luster to identify the gold content. When I told the geologist that I was seeking fossil leaves in the middle Miocene Buffalo Canyon Formation, he expressed an interest in finding a few plant specimens of his own. We then hiked over to a nearby fossiliferous outcrop and must have spent a half-hour or so picking through the diatomaceous (composed primarily of the microscopic photosythesizing single-celled algae called diatoms) siltstones and shales. While we were digging, he rather matter-of-factly asked if I had ever visited Ammonite Canyon, a "world-class ammonite collecting locality," he said, where late Triassic (roughly 205 to 200 million years old) and early Jurassic-age (about 199 to 195 million years ancient) strata yield an abundance of beautifully preserved fossils, including beaucoup, bountiful extinct cephalopods. I admitted that I hadn't heard of the place, but would certainly appreciate directions to it. Back at camp, the geologist tried his best to remember the specific route to Ammonite Canyon, but his memory failed him. The best that he could recall was that "Ammonite Canyon" was the informal name of the area he'd received on "good authority" from several folks in his profession who'd actually visited the site. My enthusiasm waned significantly. The revelation that this information concerning Ammonite Canyon was only hearsay knocked most of the wind out of my sails. Still, the phrase "world-class ammonite collecting locality" continued to bounce around in my brain, from time to time, over the next few years. Perhaps, I reasoned at last, the geologist I'd met in Buffalo Canyon had not exaggerated the claims made by his acquaintances. Maybe the line of evidence was more direct than I had originally determined it to be. After all, such geologists were trained men of science, presumably not given to imprecise observations. My reflective analysis told me that the information was probably reliable, but there was obviously one additional problem to solve: Where in the world was Ammonite Canyon? I had nightmares that this would turn into a tangled, involved search. The geologist's original description that Ammonite Canyon was but an "informal name"could conceivably lead to endlessly frustrating avenues of speculation. For example, every major mountain range invariably contains innumerable gulches, canyons, draws and washes, most of them unnamed. And, since Ammonite Canyon was admittedly a popular, unnamed geographic designation for one of these defiles in the mountains, I figured that I might have a difficult time tracking it down. And so, I began research preparations with an inspired dedication akin to attempting to locate the famous (or infamous, if you will) Lost Dutchman's Mine in Arizona--or, perhaps even formulating for possible submission my own crazy, convoluted plot for the "National Treasure" film franchise. I purchased maps. I drove to the nearest available university library to copy off reams of scientific literature pertaining to my search for Ammonite Canyon. I contacted several rock hounding clubs across the United States for geographic details. I emailed all the major university geology departments in Nevada. Zilch. Nada. No direct leads. I was genuinely dispirited. At this point I was wholly prepared to abandon the research project when the inspired idea arrived one morning after a bracing cup of coffee that perhaps I ought to try to contact the geologist who'd originally alerted me to the existence of Ammonite Canyon in the first place. That I still had in my field notebooks a reference to that individual, his name--and even the mining company he'd worked for--was in itself a minor miracle. Still, there was no guarantee of a favorable outcome. Perhaps that helpful geologist had already moved on--no longer worked for the same mining outfit. Too, I indeed recollected that when pressed for details the individual had been unable to come up with directions. It was worth a try, I decided. Off went an inquiry, mailed to the mining company. Perhaps with a little additional prodding, the geologist--or even somebody at that mining corporation--might be able to provide me with explicit directions to this mysterious Ammonite Canyon. Thus, it came to pass that I simply had to wait with at least a modicum of appropriate patience. But, when not a few weeks passed without any kind of response...well, my enthusiasm for the project began to dissipate once again--until, that is, one eventful afternoon when amidst the usual bills and unsolicited advertisements I spotted a rather inconspicuous envelope from an address I instantly recognized: that mining company I had contacted regarding the geologist who'd first mentioned to me this place called, colloquially, Ammonite Canyon. With great anticipation I ripped open that envelope to find a very welcomed letter. It seems that my original inquiry never actually made it to the geologist I'd met back in Buffalo Canyon. Somebody at the mining company had with superior initiative taken it upon himself to answer my burning question: Where in the world was Ammonite Canyon? And when I read the exact directions to Ammonite Canyon, I practically laughed out loud; turns out that, in a delicious delirium of irony, I'd already driven directly past the turnoff to it during that initial journey to--you guessed it...Buffalo Canyon. That following Spring, I loaded up my trusty vehicle with all sorts of fossil finding equipment, plus the obligatory water and supplies, and lit out for the adventure. I already knew the directions to the correct mountain range, of course; the tricky part was locating the correct dirt road that veered from asphalt to Great Basin Desert wilderness--a typical unimproved desert trail that winds its way across an alluvial fan, ever so gradually upward toward the looming presence of a fossil-rich Nevada mountain range directly ahead. Anticipation and excitation increase exponentially as one gains elevation, headed toward the mouth of the canyon in the distance. It's a mountain range packed with beaucoup geology and paleontology--an awe-inspiring spectacle consisting over over 10,000 feet of Mesozoic-age limestones, shales, and dolomites jumbled together through geologic time as if rotary-beaten. The sedimentary rocks exposed there belong to the middle through upper Triassic Luning Formation; the upper Triassic though lower Jurassic Gabbs Formation; the lower Jurassic Sunrise Formation; and the lower through early middle Jurassic Dunlap Formation. The range also contains extensive Cenozoic Era volcanic intrusives and extrusives, primarily rhyolites, rhyodacites, quartz latite welded tuffs, and tuffs of late Miocene through Pliocene geologic age, some 10 to three million years old--in addition to Cretaceous quartz monzonites and albite granites approximately 90 million years old. Many of the Miocene-Pliocene igneous rocks have been appreciably enriched in copper minerals, and there are several extensive prospects back in Ammonite Canyon that reveal colorful specimens of azurite and malachite--blue and green varieties of copper carbonate, respectively. The most fossiliferous sedimentary rocks in Ammonite Canyon belong to the upper Triassic-lower Jurassic Gabbs Formation (205 to 198 million years old) and the lower Jurassic Sunrise Formation (197 to around 193 million years ancient). In addition to the fossil ammonoids (the Triassic ceratites types) and ammonites (Jurassic-Cretaceous ammonites varieties) that occur within several limestone layers in the thick Mesozoic sequence, there are also not a few other kinds of macro and micro-invertebrate animal remains well-represented in the Ammonite Canyon exposures. These include: corals (both colonial and solitary scleractinian kinds--the type of coelenterate that replaced the tabulate and rugose corals, which went belly-up, extinct, at the close of the Paleozoic Era some 252 million years ago); brachiopods; pelecypods; and gastropods--in addition to numerous species of diminutive invertebrates (usually lumped together under the category "micro-invertebrates") such as radiolarians, foraminifers, ostracodes (a minute bivalved crustacean), microgastropods, micropelecypods, and even the last known conodonts in the geologic record (of latest Triassic geologic age--that is, a minute tooth-like food gathering calcium phosphate apparatus from an extinct lamprey-eel like organism; such conodont denticles are nevertheless unrelated to modern jaws), whose preservation is excellent considering the locally geologically disturbed nature of the sedimentary rocks in which they occur. Most of the shales of the Sunrise Formation, for example, have been altered through stressful metamorphism to a special brand of rock geologists call hornfels; hence, fossil remains tend to be rather poorly preserved there--except for one particularly fossil-rich shale zone rather low in the stratigraphic section that indeed yields plentiful casts and molds of many species of ammonites. On the other hand, the limestones, sandy limestones and sandstones of both the Gabbs and Sunrise formations have usually survived the millions of years of unkind heat and pressure, yielding many fossils in a superior state of preservation. One of the better representative fossil-bearing localities occurs not far from the prominent mouth of Ammonite Canyon. Here, the steep slopes immediately north of the dirt trail consist of abundantly fossiliferous coarsely crystalline, dark brown limestones of the upper Triassic portions of the upper Triassic-lower Jurassic Gabbs Formation. Among the commonly observed forms present are brachiopods, pelecypods, gastropods, and corals. Unfortunately, ammonites are not plentiful here, although I did manage to locate three specimens during my first visit, including one giant some six inches (15 centimeters) in diameter (Acestes gigantogaleatus, perhaps?). It came from outcrops of limestone way above the canyon floor, though, where admittedly the best collecting can be done. One doesn't need advanced mountain-climbing skills to ascend the limestone slopes, but extreme caution should be taken. The footing is, to say the least, unreasonably treacherous; wear reliable, comfortable footwear--preferably good-quality hiking boots--and take your time to spot the safest place to plant each step. The numerous excellently preserved fossils will wait for you. They've been around approximately 203 million years at this particular locality and will remain in place for a few more minutes at least, so there is certainly no need to rush to locate them, placing yourself in a precarious and potentially dangerous situation. As I learned from the geological literature I had eagerly consumed, this is a classic collecting site, well-known to the pioneering geologists and paleontologists of the 1800s. It has also been visited by hordes of both amateur fossil enthusiasts and professional paleontologists alike since at least the early 1900s. As a consequence, the fossil beds have suffered appreciable attrition, and the once unbelievably abundant ammonoid and ammonite specimens--astoundingly well-preserved in many instances--have been depleted, stored away in private collections and museum cabinets around the world. There are obviously many fabulous fossil-bearing layers throughout Ammonite Canyon, but this single site, outcropping along the main road through the canyon not far from its mouth, is certainly one of the most easily accessible and richly fossiliferous exposures known. It is hoped that visitors to this exceptional site will take but a representative sampling of paleotological material, leaving the integrity of the 203-million-year-old late Triassic faunal association intact. Immediately northeast of the first fossil locality, the road cuts through a narrows in the reddish-brown conglomerates and fanglomerates of the lower to early middle Jurassic Dunlap Formation, roughly 180 million years old. The Dunlap deposits were apparently laid down in a terrestrial paleo-environment after the lower Jurassic Sunrise Formation sea had receded, probably as alluvial outwash carried by rivers and streams from the surrounding ancestral mountains millions of years ago, a Mesozoic range that was uplifted and completely worn away before the first widespread flowering plants appeared in the geologic record some 120 million years ago. Somewhat farther up Ammonite Canyon, beyond the unfossiliferous narrows eroded in the lower middle Jurassic Dunlap Formation, the Gabbs and Sunrise formations are much better exposed. Here, marine fossils are indeed plentiful in both geologic rock units, but they tend to occur only in a few restricted zones, principally throughout a 95-foot-thick section of the Gabbs Formation, slightly above the middle--an interval of brownish-colored shaly and sandy limestone preserved in individual layers six inches to two feet thick. This is the well-known and famous "Member Three" of the Gabbs Formation, a member that yields abundant ammonoids, pelecypods, gastropods and brachiopods. One noteworthy aspect of this particular faunal association is that the fossil species recognized from it are almost identical to those that occur in similar late Triassic rocks in the Mediterranean region. Two other traceable cephalopod-rich horizons occur in the Gabbs Formation. One lies near the base of the 400-foot-thick unit, in the very oldest rocks; the other can be found just below the noted middle Member Three, in black to grayish-purple weathering limestones typically four inches to two feet thick. All three zones yield important species of ammonoids, including such key late Triassic forms as: Arcestes gigantogaleatus; Arcestes nevadanus; Chloristoceras crickmayi; Chloristoceras marshi; Chloristoceras shoshnensis; Pacites sp.; and Rhacophyllites cf debilis--plus, a curious nautiloid cephalopod called Pleuronautilus. The older of the two zones has been correlated (that is, it's the same geologic age) with a major mollusk-bearing section in the Santa Ana Mountains of southern California. At a stratigraphic point roughly 56 feet (17 meters) below the base of the overlying (and younger) lower Jurassic Sunrise Formation--within the Gabbs Formation--there is recorded in the rocks at Ammonite Canyon a traumatic event of worldwide import--the classic end-time Triassic event, a great mass extinction some 199.6 million years ago. That's when, over an unbelievably brief period of geologic time--only 10,000 years, perhaps--some 20 percent of all marine life died out, and up to half of all terrestrial animal life disappeared, as well. The numerous paleo-ecological niches then left vacant famously ushered in the dawn of "Jurassic Park"--when dinosaurs began to dominate our planet's terrestrial domains during the Jurassic and succeeding Cretaceous Periods. Stratigraphers continue to rave, proclaim with considerable convinction, that the well-exposed marine stratigraphic section developed in Ammonite Canyon remains one of the world's thickest, most complete, and reliably fossiliferous exposures of rocks dating from the day of end-time Triassic doom. In Ammonite Canyon, the geologic transition from late Triassic to early Jurassic times lies within the upper (younger) phases of the Gabbs Formation. The precise boundary between the Triassic and Jurassic Periods has been placed by Mesozoic Era specialists at the first occurrence of two key ammonite species--Psiloceras tilmanni and Psiloceras spelae. Directly above the Gabbs Formation lies the lower Jurassic Sunrise Formation, whose lowermost (oldest) brownish sandy limestones and younger shales yield a true abundance of ammonites and other invertebrate remains. Key species of cephalopods from the lower limestones include such ammonites as: Caloceras peruvianum; Chloristoceras minutum; Kammerkarites sp.; Neophylites sp.; Nevadaphylites sp.; Odoghertyceras deweveri; Pleuroacanthites mulleri; Psiloceras marcouxi; Psiloceras pacificum; Psiloceras polymorphum; and Transipsiloceras transiens. Also present in the oldest limestone zones of the Sunrise Formation are numerous nicely preserved solitary scleractinia corals not yet formally described in the scientific literature, plus several species of rynchonellid brachiopods, pecten-style pelecypods, and various gastropods. Higher in the Sunrise section--in strata approximately 193 million years old (mid Sinemurian Stage of the early Jurassic Period)--several species of ammonites occur as casts and molds through several tens of feet of pale purple-weathering shales. Almost all of the fossil-bearing layers in the Gabbs and Sunrise Formations closest to the main road have been heavily prospected over the years. I had better luck when I hiked away from the primary wash, up any of the minor gulches and gullies that intersect it. Virtually all of my early Jurassic ammonite finds, for instance, came from a single narrow nondescript dry wash, above Ammonite Canyon road, in a localized exposure of transitional Gabbs-Sunrise strata. Be advised once again, though. The ammonoids and ammonites are far from common at the surface anymore. Because the extinct cephalopods are such prized paleontological items, sought by many collectors throughout the world, don't expect to step out of your vehicle and load up on perfectly preserved specimens. This just isn't going to happen. One almost needs to acquire a "sixth sense" about where to look for ammonites--attempting to out-guess the competition, as it were. Although ammonoids and ammonites are no longer exceptionally abundant, the other "less glamorous" Mesozoic marine invertebrates remain plentiful. Brachiopods, pelecypods, solitary corals, colonial corals (found only within late Triassic strata at Ammonite Canyon), and gastropods are frequently overlooked, or ignored, by eager prospectors bent on locating the famed Ammonite Canyon coiled cephalopods, and many exquisitely preserved forms weather free for the taking from their calcium carbonate matrixes. While hiking along the gravel road through Ammonite Canyon, one will likely observe relatively common chunks of colorful blue-green copper minerals scattered about. These have been washed down from volcanics and geologically altered Mesozoic-Cenozoic rocks that outcrop farther up the canyon. As a matter of fact, several years ago a prestigious mining company decided to claim a significant portion of Ammonite Canyon for future copper exploration. Don't worry, though. At last check, they haven't closed off the canyon just yet, though visitors will have to obey all private property rights should such formal mining operations ever commence. Ammonite Canyon instantly became one of my favorite fossil localities. Here is a remote region in a rugged strata-jumbled range in Nevada, where wonderfully preserved ammonoids, ammonites, brachiopods, corals, pelecypods, and gastropods can be found in a classic Great Basin Desert setting--Mesozoic-age specimens some 205 to 195 million years old, the preserved remains of invertebrate animals that span the world-famous end-time Triassic mass extinction. Few places on Earth record such a well-exposed, accessible, and inclusively fossiliferous marine Triassic-Jurassic-age transition period. With a single step, one can actually move 100,000 years in geologic time: from the end-time latest Triassic 199.7 million years ago, to the very beginning of the succeeding Jurassic Period 199.6 million years ancient, when fully one-fifth of all marine life no longer existed and roughly half of all animals on land had vanished. |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: (1) A seeker of Mesozoic paleontology explores geological exposures in Ammonite Canyon, Nevada; he is standing at the contact between the Upper Triassic portion of the Upper Triassic-Lower Jurassic Gabbs Formation, which here yields abundant and well preserved ammonoids, colonial scleractinian corals, gastropods, and pelecypods some 205 to 203 million years old (late Norian through early Rhaetian Stage geologic age) and the late lower Jurassic Dunlap Formation of Toarcian Stage age, approximately 180 million years old. The large brownish boulders are conglomerates and fanglomerates that belong to the terrestrial late Lower Jurassic Dunlap Formation; slope-forming strata directly behind the individual are shales that accumulated in the upper Triassic section of the upper Triassic-lower Jurassic Gabbs Formation. (2) An explorer of the Mesozoic Era examines fossiliferous limestones and shales belonging to the lower Jurassic part of the upper Triassic-lower Jurassic Gabbs Formation in Ammonite Canyon, Nevada; the rocks here are roughly 198 to 196 million years old (Hettangian Stage of the Jurassic), deposited just after the great mass extinction at the close of the Triassic Period (about 200 to 199 million years ago). |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: (1) An enthusiast of Mesozoic Era paleontology examines shales and limestones along a slope weathered in the upper Triassic section of the upper Triassic-lower Jurassic Gabbs Formation, Ammonite Canyon, Nevada. Here occur many varieties of ammonoids (Triassic ceratites types), in addition to colonial scleractinian corals and several species of gastropods and pelecypods roughly 205 to 202 million years ancient, deposited in what stratigraphers call the late Norian Stage through Rhaetian Stage of the late Triassic Period. (2) Note the individual standing along the lower slopes, at roughly lower center left of photograph. He is standing on the ammonoid (Triassic ceratites types) -ammonite-bearing upper Triassic section of the upper Triassic-lower Jurassic Gabbs Formation in Ammonite Canyon, Nevada--rocks dated at around 205 to 202 million years old (late Norian Stage through early Rhaetian Stage geologic age). Dirt road at right passes through massive reddish-brown, unfossiliferous terrestrial conglomerates and fanglomerates of the late lower Jurassic Dunlap Formation, Toarcian Stage age, approximately 180 million years old. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: (1) The reverse side of the ammonite seen at the top of this web page, called scientifically Psiloceras pacificum, from the oldest limestone layers of the lower Jurassic Sunrise Formation, Ammonite Canyon, Nevada; (2) An ammonite Psiloceras polymorphum from the oldest limestone layers of the lower Jurassic Sunrise Formation, Ammonite Canyon, Nevada. The cephalopods had weathered out of sedimentary rocks that accumulated during the Hettangian Stage of the lower Jurassic Period, approximately 198 million years old. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: (1) An ammonite still resting on its limestone matrix--Psiloceras polymorphum--from the oldest limestone layers of the lower Jurassic Sunrise Formation, Ammonite Canyon, Nevada. The extinct cephalopod derives from the earliest sedimentary deposits of Hettangian Stage of the Jurassic Period, around 198 million years old; (2) An impression (mold) of an ammonite on a chunk of shale from the lower Jurassic Sunrise Formation, Ammonite Canyon, Nevada--genus is Pseudaetomoceras sp. It's from the mid Sinemurian Stage of the Jurassic Period, about 193 million years old. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: Both specimens are casts of ammonites, preserved on chunks of shale from the lower Jurassic Sunrise Formation, Ammonite Canyon, Nevada--genus is Pseudaetomoceras sp. The paleontological remains came from roughly the mid Sinemurian Stage of the Jurassic Period, approximately 193 million years ago. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: Both specimens are ammonoids--genus Arcestes sp.-- from the upper Triassic portion of the upper Triassic-lower Jurassic Gabbs Formation, Ammonite Canyon, Nevada. They were found in strata deposited during the Rhaetian Stage of the Triassic Period, approximately 202 million years ago. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger images. Left to right: (1) An ammonoid--genus Arcestes sp.--from the the Upper Triassic section of the upper Triassic-lower Jurassic Gabbs Formation, Ammonite Canyon, Nevada. Specimen was found in strata deposited during the Rhaetian Stage of the Triassic Period, approximately 202 million years ago; (2) An ammonite from the lower limestone layers of the lower Jurassic Sunrise Formation, Ammonite Canyon, Nevada--called scientifically, Psiloceras polymorphum. It is from the earliest sedimentary accumulations of Hettangian Stage of the Jurassic Period, roughly 198 million years old. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: Both specimens are ammonites--genus Nevadaphylites sp.--from the oldest limestone layers of the lower Jurassic Sunrise Formation, Ammonite Canyon, Nevada--from the earliest parts of Hettangian Stage of the Jurassic Period, roughly 198 million years ago. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: Both specimens are ammonites--Psiloceras pacificum--still resting on their limestone matrixes from the lower limestone layers of the lower Jurassic Sunrise Formation, Ammonite Canyon, Nevada. They were entombed in strata representing the earliest Hettangian Stage of the Jurassic Period, about 198 million years old. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: (1) A so-called "cannonball" ammonoid--possibly Acestes gigantogaleatus--photographed as it resided in-situ (greenish-colored corners were later photoshopped in) in the Upper Triassic portion of the upper Triassic-lower Jurassic Gabbs Formation, Ammonite Canyon, Nevada--in actual dimension, the ammonite is roughly 15 centimeters (6 inches) in diameter. Specimen came from the Rhaetian Stage of the Triassic Period, approximately 202 million years ago; (2) A pedicle view of an undescribed rhynchonellid brachiopod from the lower Jurassic Sunrise Formation, Ammonite Canyon, Nevada--it came from strata representing the earliest Hettangian Stage of the Jurassic Period, about 198 million years old. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: (1) Undescribed gastropods from the upper Triassic section of the upper Triassic-lower Jurassic Gabbs Formation, Ammonite Canyon, Nevada. They derive from the latest Rhaetian Stage of the Triassic, roughly 202 million years old; (2) An undescribed pecten, still residing on its original sandy limestone matrix, from the lower Jurassic Sunrise Formation, Ammonite Canyon, Nevada. The mollusk came from the earliest Hettangian Stage of the Jurassic Period, approximately 198 million years ago. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: Both specimens are undescribed solitary, stony Scleractinia corals from the lower Jurassic Sunrise Formation, Ammonite Canyon, Nevada. They were found in strata representing the earliest Hettangian Stage of the Jurassic Period, about 198 million years old. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: Both specimens are undescribed solitary, stony Scleractinia corals from the lower Jurassic Sunrise Formation, Ammonite Canyon, Nevada. They were found in strata representing the earliest Hettangian Stage of the Jurassic Period, about 198 million years old. |

|