|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Take virtual field trips to two classic, world-famous late Triassic (late Carnian to Norian Stage age--roughly 218 to 210 million years old) fossil localities in Nevada. First off, observe in-situ at Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park, in what geologists call the Upper Triassic Luning Formation, the remains of several huge ichthyosaurs--an extinct marine reptile that ruled Mesozoic Era seas for many millions of years--exposed in a fossil quarry, similar in scientific conservation style to the late Jurassic geologic age bone quarry at Dinosaur National Monument in Utah-Colorado; and then, drive outside the state park's boundaries to find pelecypods, gastropods, brachiopods and ammonites (Triassic Period types are also called ammonoids) in the very same rock strata that preserved the ichthyosaurs. Next, head over to Coral Reef Canyon, several miles from Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park, a place situated on America's public lands, where paleontology enthusiasts can collect many species of corals, sponges, echinoids (sea urchins), gastropods, pelecypods, belemnites (straight-shelled cephalopods related to modern squids) and ammonites (such Triassic forms are also called ammonoids) from the Upper Triassic Luning Formation. |

|

|

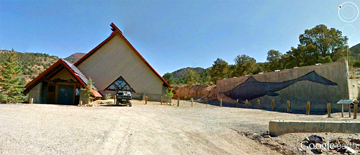

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right. (1) A number of members of the Nevada Paleontological Association gather at the Visitors' Quarry parking lot at Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park, Nye County, Nevada, in front the great bas-relief model of a 57 foot-long ichthyosaur, Shonisaurus popularis, Nevada's state fossil, to listen to Dr. Jennifer Hogler discuss her field of expertise--the ichthyosaurs of the Upper Triassic Luning Formation, Nevada; (2) Note brown and white CJ7 jeep parked along the dirt trail, at lower center, in Coral Reef Canyon, Nevada. The bold exposures here belong to the geologically oldest subunit "member one" of the Upper Triassic Luning Formation, which in Coral Reef Canyon yields prolific quantities of tangled reef-forming corals and sponges, in addition to weathered-free brachiopods, pelecypods, gastropods, echinoids (sea urchins), belemnites (straight-shelled cephalopods related to squids), ammonites (an extinct order of cephalopod; the Triassic types are also called ammonoids), and not a few ichthyosaur skeletal elements. |

|

Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park in Nye County, Nevada, contains the greatest concentration of some of the largest ichthyosaurs ever found. Although it's true that a later discovery in Canada disclosed a species that actually grew somewhat bigger than the Nevada examples--recognized for many years as the largest ever recorded--the Nye County locality nevertheless remains unique in its abundant association of huge ichthyosaurs. During late Triassic geologic times, these were enormous predatory marine reptiles that grew to 60 or more feet in length and by many estimates could have weighed in excess of 50 tons. Two-hundred and eighteen million years ago they lived in a tropical sea that covered much of present-day west-central Nevada, plus portions of Oregon, Washington, California and British Columbia, Canada, as well. The now stone skeletons at Berlin-Ichthyosaur park have been exposed by paleontologists in a quarry in Union Canyon, roughly a mile and a half southeast of the old mining camp of Berlin, now a ghost town protected in what's colloquially called a state of "arrested decay." The fossil reptile bones of the great "fish-lizards" can be observed in-place in the sedimentary rocks of the Luning Formation--an ichthyosaur graveyard, the only one of its kind in the United States. In addition to ichthyosaurs, many other kinds of aquatic life thrived in that ancient ocean some 218 million years ago. Pelecypods, gastropods, ammonites (such Triassic types are also called ammonoids), brachiopods, and conodonts (diminutive tooth-like structures, unrelated to modern jaws, derived from an extinct lamprey eel-like hemichordate; seen only in the residues of carbonates dissolved by acetic or formic acid) can also be found in the late Triassic rocks present in Union Canyon. Most of the famed fossil-bearing section is currently included in the Nevada state park system, but happily for folks infused with paleontological enthusiasm there are not a few areas outside the Berlin-Ichthyosaur park where at last field check fossils can still be collected legally, without formal prior approval from the authorities; of course, always conduct necessary due diligence--contact officials with controlling jurisdiction (AKA, BLM or Unitied States Forest Service, for example) to determine a specific locality's present status. The fossil-yielding region is easily reached. Take the well-posted turnoff to Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park just north of Gabbs along State Route 361. This junction lies 29 miles south of Highway 50 and 34 miles north of Highway 95. Go east roughly 20 miles or so, through classic Great Basin territory, to the intersection with the dirt road to Ione (which is around seven miles to the north). Bear to the right here (south) in the direction of Berlin ghost town, which lies just south of the junction. This is an interesting little ghost town, part of the Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park. Many of the old wooden buildings have been mildly renovated (such as they are, as it were), and footpaths throughout the site lead to instructive plaques whose writings detail life and activity in a typical Nevada silver mining camp of the late 1800s, through the early 1900s. The original silver ore locations at Berlin were made in 1895 by a state Senator Bell, who soon sold his property to John G. Stokes of New York. In 1898, the Nevada Company, with a notorious reputation for its aggressive acquiring of mineral rights, bought out the Stokes claims. In an attempt to consolidate its regional influence, the company quickly purchased the Pioneer and Knickerbocker mills in the vicinity of Ione, moving all of the machinery to the Berlin site. What the Nevada Company intended to do was construct a state of art, brand new thirty-stamp mill to begin a systematic and, with a fair amount of luck, profitable development of the reportedly extensive ore bodies. During the boom years roughly 250 persons lived in Berlin. They had a general store, post office, and even a stage line to other mining towns in the immediate area. Although the silver ore reserves had initially appeared worthy of exploitation, the yields turned out to be rather disappointing. In 1909, the big mill originally financed by the Nevada Company shut down. But an article that year in a newspaper at Goldfield, Nevada, asserted that there was certainly enough silver ore remaining to fuel the mill for an additional three years. Nobody seemed to believe this optimistic evaluation, though. Berlin had apparently run its course. Then, in 1911, some investors decided that it might be worthwhile to process the low grade, spent mining tailings at Berlin--the stuff left over from the original operations. A fancy new and improved 50-stamp mill was constructed (the hulk of which towers above the road to the ichthyosaur bone bed) and the mounds of tailings went through a second pulvarization. The 50-stamper operated for three years, extracting a paltry two dollars and fifty cents to the ton of material processed. During World War II, all of the equipment in the mill was systematically hauled off, stripped, its metal evidently used in the allied effort. Continue south along the dirt road through Berlin. To the west of the path spreads the awe-inspiring expanse of Ione Valley, a great sage-coated basin that hugs the base of the Shoshone Mountains. At a point approximately eight-tenths of a mile from the road back to Gabbs and State Route 361, the path turns east through pinyon pine and juniper-studded Union Canyon, which has been carved in the Upper Triassic Luning Formation, deposited here in the vicinity of Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park during the late Carnian through early to middle portions of the Norian Stages, about 218 to 210 million years old. Elsewhere in Nevada, the Luning Formation includes strata solely of early to middle Norian Stage geologic age--that is, around 216 to 210 million years old. The limestones and shales exposed throughout Union Canyon not only contain the world-famous ichthyosaur bone graveyard, but in addition a wealth of excellently preserved mollusks, including ammonites, pelecypods and gastropods. Almost immediately upon turning east to Union Canyon, you will spot to the right of the road, in the distance, the impressive A-frame construction which houses the ichthyosaur skeletal quarry. At last check, the fossils are on display here on weekends only throughout about half of the year, accessible to the public for a nominal fee, from around mid March to mid November. One would do well, though, to check with the ranger station in Berlin for specific times; in other words, don't rely completely on published time schedules provided on the internet. Paleontologically informed rangers give talks at the quarry site, where the individual skeletal remains of nine huge ichthyosaurs have been excavated and left in place--all in their original burial positions--in sedimentary rocks deposited roughly 218 million years ago during the youngest phases of what stratigraphers call the Carnian Stage of the late Triassic. A typical tour usually lasts about 40 minutes and consists of a general geological, anatomical and behavorial overview of ichthyosaurs, plus a detailed explanation of all the specific kinds of skeletal elements preserved on the quarry floor--skulls, jaws, vertebrae, flippers and ribs, among others. It's a genuinely educational, inspiring and fun tour. At the quarry parking lot you can also view a 57-foot bas-relief, life-size reconstruction of a Union Canyon ichthyosaur, Nevada's state fossil, Shonisaurus popularis--a specimen that in actual life probably weighed in excess of 40 tons. The first fossil ichthyosaur bones in Union Canyon were certainly observed by silver-gold prospectors in the 1890s. Perhaps the old-time miners really didn't fully appreciate the finds, but as the often-told story goes, folks in Berlin regularly placed them as decorations in their fireplace hearths. Some of the more ingenious individuals even used the large disc-shaped vertebrae as dinner plates; several historians, though, have dismissed out of hand this particular story, claiming that the genesis of it derives from famed professor Charles L. Camp--an ichthyosaur aficionado intimately involved in the early scientific investigations of the Union Canyon bone bonanza--who supposedly exclaimed with excitation that the creature's eyes were as large as dinner plates. Then again, nobody with definitive documentation has ever disproved the claim, either. The pioneering scientific investigation of the ichthyosaur deposit came in 1929 when a geology professor at Stanford University, Siemon W. Muller, visited Union Canyon. He studied the exposed vertebrae specimens in the late Triassic strata and determined that they belonged to an ichthyosaur. While the find was incredibly significant, Muller decided that there was no use in attempting to excavate the fossils, at that time. First off, he concluded, they were very large--way too bulky to transport safely back to civilization from such a remote region. And second, the ichthyosaur skeletons were buried far too deep in the hard sedimentary section; he could not be certain that a quarrying operation would be successful. Indeed, he speculated such digging might actually do more harm than good. In the end, Muller returned to Stanford University without really determining the full extent of the fabulous fossil occurrence. Perhaps he was convinced that he had obeyed that golden Shakespearean rule of conduct, that "discretion is the better part of valor." To Muller's credit, it must be emphasized of course that some reports disclose that when he finally returned to Stanford from his visit to Union Canyon, he tried to drum up interest in his ichthyosaur finds. Fortunately, more actively persistent individuals would not let the fossils rest in peace in those remote reaches of the Great Basin. An acquaintance of Professor Muller, Margaret Wheat--an avid amateur fossil hunter--visited Union Canyon in the summer of 1952. What she saw immediately impressed her: nicely preserved ichthyosaur bones still partially articulated; that is, the skeletal elements were essentially aligned in their natural anatomical relationships. She then contacted Dr. Charles L. Camp, a noted paleontologist and director of the University California Museum of Paleontology in Berkeley. The pair returned to the locality in 1953. It didn't take Dr. Camp long to determine the grand importance of the exposed ichthyosaur skeletons--that here was perhaps the greatest accumulation of the largest ichthyosaur specimens ever encountered. A major paleontological dig was definitely in order. The scientific excavations began in 1954 under the direction of Dr. Camp and his colleague, Samuel P. Wells. Along with a select group of paleontology and geology students, the scientists carefully removed the thick, induratated limestone overburden to expose the mineralized remains. The digging was strenuous, tedious and exacting. In all seven field seasons were required to get the job completed: from 1954 through 1957, then a second session from 1963 to 1965. When the "smoke had cleared," Dr. Camp had identified at least 37 adult ichthyosaurs from the Upper Triassic Luning Formation of Union Canyon. These included three distinct species, each of which exceeded 37 feet in length. One species, Shonisauris popularis (named Nevada's state fossil, by way), was for many years the largest ichthyosaur ever discovered (a later find in Canada exceeds by somewhat the Union Canyon critter)--the ultimate predator of the late Triassic seas, a frightening giant that grew to almost 60 feet in length and weighed 40 to 50 tons. Ichthyosaurs were exclusively marine, sea-going reptiles. They first appear in the geologic record during the middle portion of the Triassic Period, about 240 million years ago. The earliest forms grew to an average length of about three to 30 feet, the latter roughly the size and weight of a modernday killer whale. One mid-Triassic species discovered in the New Pass Range of north-central Nevada in 1868 was described scientifically by famous paleontologist Joseph Leidy as belonging to a new genus of ichthyosaur, Cymbospondylus. It had a three-foot long skull filled with sharp conical teeth, perfect adaptions for preying on a balanced diet of shellfish (ammonites, belemnites and various other cephalopods), small ichthyosaurs (such as Mixosaurus cornalianus, an undersized type that grew to only three feet), and any variety of fish around which it could clamp its vice-like jaws. Later, more advanced specimens of ichthyosaurs apparently continued these feeding patterns. In comparison with ichthyosaurs studied from the late Triassic and Jurassic Period, the tail of the early species was rather primitive; there was no bend to it, which may indicate that it possessed a limited ability to propel itself through the water. It is also interesting to note that the eye socket of the 30-foot Cymbospondylus was actually smaller than its diminutive three-foot long relative Mixosaurus cornalianus. Ichthyosaurs reached their zenith of adaptation in the late Triassic through mid-Jurassic seas. For approximately 55 million years they were the so-called biggest fish in pond, at the very top of the marine biological food chain. While the species of the Jurassic Period were much smaller than their Triassic predecessors--they grew to a maximum length of only 12 feet--the later ichthyosaurs possessed stream-lined bodies built for speed and agility. By the close of the Jurassic, though, approximately 165 million years ago, the numbers of species had been greatly reduced. Ichthyosaurs indeed survived the Jurassic Period, but could only manage to hang on half-way through the succeeding Cretaceous Period of the Mesozoic Era, eventually going extinct by 90 million years ago, roughly 25 million years prior to the demise of the dinosaur. Many reasons have been advanced to account for the ichthyosaur's disappearance. Some investigators suggest that the rise of plesiosaurs and monosaurs, reigning reptilian terrors of the Cretaceous seas, contributed to their inevitable decline. Another line of thought holds that the increase in numbers of sharks hastened their demise, that these large predatory fish began to feast on the once invincible ichthyosaur, reduced in Cretaceous times to a modest-sized creature less than 12 feet long. In the end, perhaps ichthyosaurs were just too specialized to last. During their doomed Cretaceous days they subsisted primarily upon cephalopods, such as ammonites, belemnites, nautiloids and perhaps giant squid (if true, then ichthyosaurs anticipated by many millions of years the feeding habits of modern sperm whales), as well--molluscan varieties, excepting the squid, that in a paleontologically provocative coincidence began their own sure decline to disappearance in the middle Cretaceous--just as the ichthyosaurs went extinct. It is not known for certain how the ichthyosaurs of Union Canyon came to be preserved, but investigators have developed three competing explanations of what happened here some 218 million years ago. At present, many vertebrate paleontologists believe that all of the ichthyosaurs preserved in the late Triassic Luning Formation at Union Canyon accumulated gradually as individual deaths--that is, not catastrophically as a group of animals--in rather deep, oxygen-poor waters--perhaps the result of natural deaths, or a stray kill here and there, from anoxic sea waters or poisonous algae blooms. The scientists base their conclusions primarily on how they choose to interpret the geologic meaning behind the lithology of the sedimentary rocks within which the ichthyosaurs have been preserved--a sedimentary deposit of thin-bedded argillaceous calcium carbonates called by many geologists a "shaly limestone"--a type of rock whose deposition, they say, probably occurred in deeper waters, not in relatively shallow areas of the late Triassic sea. Other geologists interpret the evidence differently, of course, and see shallow water, even a beach deposit, where different eyes would observe an abyss. A more recent avenue of speculation borders perhaps on the fanciful, if not outright fantastical. One imaginative, creative visitor to the fossil quarry at Union Canyon came away with the distinct impression that he could see a cephalopodic pattern in the way the ichthyosaur vertebrae were aligned in the rocks. That pattern reminded the visitor of the suction cups on the arms of an octopus. And that observation led, further, to the idea that perhaps the 37 to 60 foot-long Luning Formation ichthyosaurs were attacked by something even more terrifying in the Triassic--yes...a giant octopus (a Kraken of mythology, as it were), who grasped the passing ichthyosaurs with its monstrous tentacles: hauling the unlucky vertebrates back to his invertebrate's lair; consuming there the marine reptiles; and then curiously arranging the vertebrae in a quasi-self-portrait, reminiscent of its own suckers. But, the original idea proposed by Dr. Charles L. Camp remains perhaps the most compelling explanation yet offered. At that date, some 218 million years ago, present-day Union Canyon was located slightly north of the equator, near the shoreline of a warm water tropical embayment, whose original position has of course been transported by the slow, sure, inevitable laws of plate tectonics to its present place in an arid Great Basin Desert. Ichthyosaurs and other sea-going animals were able to swim in and out of this bay, returning to the open marine waters whenever they so desired. But then something treacherous happened. Rapidly falling tides stranded at least 37 fully grown ichthyosaurs on a lonely mudflat. No human eyes were there to witness the slow suffocation of these magnificent sea reptiles when they were unable to lift their massive 40 to 50 ton bodies off of the beach. Yet, it must have been a haunting sight. An ichthyosaur was perfectly adapted to a life exclusively in the ocean; it could not hope to operate once out of water. An identical phenomenon happens today when whales and porpoises are occasionally beached. When the tides returned, the ichthyosaur carcasses were aligned parallel with wave action near the shoreline. Scavengers plucked the reptilian flesh, helping to expose the bones to the elements. In time, only the skeletons of the great marine reptiles remained along the ooze-rich mudflat. Over the course of geologic time, the bones were eventually covered by thousands of feet of sandstones, shales, limy muds and limestones belonging to the Upper Triassic Luning and Gabbs Formations and the Lower Jurassic Sunrise and Dunlap Formations. Minerals brought in by percolating lime-rich water slowly replaced the organic content in the skeletons. Given enough time, perhaps millions of years, the once living, breathing ichthyosaurs finally turned to stone. The sediments that accumulated in the late Triassic through middle Jurassic seas were apparently unaffected by mountain-building processes until approximately 60 million years ago. This is when the western end of the continental plate carrying North America northward began to collide with what geologists call the Farallon Plate. Tectonic activity began on a dramatic, widespread scale. Great faults appeared across what's now west-central Nevada, thrusting the once flat-lying marine-originated muds, silts sands and carbonates thousands of feet upward. The late Triassic mudflat, with its mineralized ichthyosaur bones, became part of the Shoshone Mountains, uplifted some 7,000 feet higher than the level of the sea in which it was originally deposited. Erosion of the ichthyosaur-bearing Lining Formation began in earnest during the glacial stages of the Pleistocene Epoch two million years ago. Hundreds of feet of sedimentary rock were worn away until at last, some few thousand years ago, the ichthyosaurs came to their first light of day in 218 million years. The fossil ichthyosaurs of Union Canyon were first officially protected in 1955 when the Nevada legislature created Ichthyosaur Paleontologic State Monument; many years later, with the inclusion of Berlin ghost town, the locality became known as "Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park." In 1966, the distinctive A-frame shelter over the main fossil quarry (called the Visitors' Quarry) was erected, an excellent and attractive means of protecting the 218 million year-old remains in the rocks. And finally, in 1975, Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park became a Registered Natural Landmark--a designation reflecting a region of "exceptional value to the citizens of the United States." Many fossils have been recovered from the Upper Triassic Lining Formation of Union Canyon. At the Visitors' Quarry (also affectionally called the "Fossil House"), display cases contain beautiful specimens of ammonoids and pelecypods that date from the day of the ichthyosaur. Exceptionally fossiliferous rocks occur at the western end of Union Canyon, but those exposures lie within the park's boundaries; obviously, they are off-limits to unauthorized amateur paleontology enthusiasts. As a matter of fact, the Union Canyon Luning Formation outcrops used to reign supreme as world-famous producers of several key genera of late Triassic transitional Carnian-Norian Stage ammonites, plus three kinds of nautiloid cephalopods, as well. Unfortunately, repeated intensive professional paleontological expeditions, in addition to frequent armateur hobby collecting (prior to the area's status as a state park, of course) spanning 100-plus years has reduced surface cephalopodic occurrence to virtual nonexistence. There are still plenty of other kinds of invertebrates to observe there, one must note--pelecypods and brachiopods and gastropods, primarily (with conodonts present locally). Stratigraphers allow, though, that should paleontologists conduct additional formal, structured fossil quarrying at Union Canyon, exposing more ichthyosaur skeletons in the rocks, abundant ammonites, preserved in their original layers of zonation--one key species stacked atop another in succession--could again be studied. Among the ammonites (such Triassic ceratites varieties are also referred to as ammonoids, by the way) described from the Luning Formation of Union Canyon were such important genera as Klamathites, Mojsisovicsites, Tropites, Tropiceltites, Guembelites and Discophyllites. But do not despair. The fossiliferous Luning Formation is exposed over a rather extensive area in this part of Nevada's Great Basin terrain. While it's true that all of the principal mollusk-ichthyosaur-bearing horizons have been officially protected, representative outcroppings of fossil-yielding Luning Formation strata can still be explored outside the park's boundaries. The trick, of course, is to know precisely where those boundaries lie. And that means obtaining the most recent, up-to-date map one can find. Territory outside Berlin-Ichthyosaur Park lies within a United States National Forest, administered by the US Forest Service, where hobby collecting of reasonable amounts of common invertebrate fossil specimens has long been allowed--although that too could change without any manner of advance warning. Be sure to check with the local rangers in Berlin for the most recent fossil collecting regulations. Of course, even when investigating outside Berlin-Ichthyosaur park, all fossil vertebrate remains encountered must be left where found, unless one has secured a special use permit, a permit given solely to individuals with a minimum B.S. degree from an accredited university, whose research projects can be verified as authentic by independent investigations. Taking photographs of fossil vertebrates, when found, is not yet illegal. Ok--so now you've completed the necessary due diligence, your proverbial homework, and you're presently ready to head out into the hills surrounding Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park to fossil prospect. Where to look? One would do well to watch for the so-called "shaley limestone member" of the Upper Triassic Luning Formation, the very same stratigraphic unit that preserved the ichthyosaur bone bed, plus enormous quantities of mollusks (ammonites-pelecypods-gastropods) and to a lesser extent brachiopods back at the Visitors' Quarry. In natural outcrop, it's a thinly bedded, dark brown to black silty limestone, sometimes visible along the hillsides as poorly to decently exposed "ribs" and ledges. More often, though, junipers and pinyon pines have formed a dense "pygmy" forest atop the late Triassic rocks, which have been so brutally eroded that they resemble little more than an alluvial soil cover. But in reducing the strata to rubble, the powers of erosion have also released numerous fossil mollusks and occasional brachiopods once embedded in the limy matrix. Simply hike away from the dirt roads, into the pleasing pitch-scented perfume of the pines and junipers, and watch carefully for the perfect pelecypods (Septocardia types with both valves intact) and gastropods, primarily (a few ammonites and brachiopods can also be located)--all weathered out whole and intact, ready to be collected. And keep your eye out for rattlesnakes, too! During my last visit, I had one close encounter of the viperous variety--an angered anguiform animal buzzing its tail off at my intrusion into its domain. I did not contest his territorial demands. Although I have run into two rattlesnakes during my explorations here, rest assured that the snake population is likely no denser than anywhere else in the Great Basin. It's just that I have a special ability to locate the reptiles in the bush. For those wishing to spend a few days at Union Canyon, a clean spacious campground can be found near the fossil quarry. It is well posted and easy to locate. If a visit is made during summer, be prepared for warm temperatures, plus swarms of blood-sucking gnats. At least one of the species of insect is especially virulent, causing maddening allergic reactions that typically do not flare up until a day or so after the bite. No one brand of insect repellent seems to provide a reliable safeguard against the onslaught. Expect maximum protection for a couple of hours, at most, then you're on your own. Two-hundred and eighteen million years ago, Union Canyon was a tropical bay situated near the equator. The warm waters supported many species of ammonites, pelecypods, gastropods, brachiopods, conodonts, and ichthyosaurs. Today, the fossilized remains of these animals can be found the Upper Triassic Luning Formation deposited in that Mesozoic sea--a vast ocean that was alive with the great fish-lizards, the ichthyosaurs, who in their day were just as graceful and as efficient predators as our modernday killer whales. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: (1) A vintage 1971 photograph, taken by a relative of mine--it's a view eastward in Union Canyon, Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park (then known as Ichthyosaur Paleontologic State Monument), to the distinctive A-frame structure that houses the world-famous ichthyosaur bone bed, where nine of the great marine reptiles, each exceeding 37 feet in length (one measures almost 60 feet long), can be viewed along the floor of a paleontological quarry, similar in scientific conservation style to the late Jurassic-age quarry at Dinosaur National Monument, Utah-Colorado; (2) A vintage 1971 photograph, taken by a relative of mine, of the bas-relief model of Nevada's state fossil displayed at the Visitors' Quarry parking area, Shonisaurus popularis--all 57 feet of it, one of the largest ichthyosaurs ever discovered--the huge fish-lizard preserved in stone at Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park in Nye County, Nevada. |

|

|

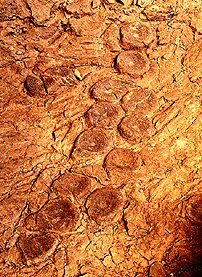

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: A Google Earth street car perspective--snapped in September, 2015--that I edited and processed through photoshop. It's a look eastward to the Visitors Quarry at Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Monument, Nye County Nevada, a view that includes: The parking lot; the western side of the A-frame structure that houses the world-famous ichthyosaur bone bed, where lie nine of the great marine reptiles--each exceeding 37 feet in length (one measures almost 60 feet long); and the famous bas-relief model of the 57 foot-long state fossil of Nevada, the ichthyosaur Shonisaurus popularis, one of the largest ichthyosaurs ever discovered.Right--Two roughly parallel rows of disc-shaped vertebrae from two huge Shonisaurus popularis ichthyosaurs, preserved in limestone of the upper Triassic Luning Formation at the Visitors Quarry, Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Monument, Nye County, Nevada. Both photographs from year 2016, courtesy an individual who goes by the cyber-name Sagebrush Steve. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: (1) Dr. Jennifer Hogler--one of the premiere ichthyosaur specialists in the world--with a model of an ichthyosaur in hand--and the fossil quarry directly behind her (the quarry is composed of a carbonate bed in the "shaly limestone member" of Luning Formation)--discusses late Triassic times in what is today Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park, Nye County, Nevada--a vast, arid Great Basin land that roughly 218 million years ago was a tropical sea situated just north of the equator; (2) Field trip attendees with the Nevada Paleontological Association get all the low-down on ichthyosaurs from one of the most knowledgeable ichthyosaur experts in the world--Dr. Jennifer Hogler--just outside the Visitors' Quarry A-frame building, Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: (1) A fossil prospector examines typical weathered exposures of the Upper Triassic Luning Formation, outside the boundaries of Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park, Nevada; here, a dense "pygmy" forest of pinyon pine and juniper grows atop brutally eroded sediments of the "shaly limestone member," the same specific rock subunit that preserved the ichthyosaurs, ammonites and other paleontological specimens back at the Visitors' Quarry; (2) A seeker of late Triassic times searches for invertebrate fossils--pelecypods, gastropods, brachiopods and ammonites (the Triassic types are also called ammonoids) weathering out of the Luning Formation--on public lands outside of Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park. |

|

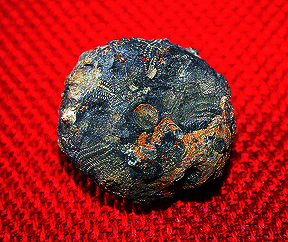

Numerous species of late Triassic-age fossils (roughly 228 to 200 million years old) have been identified from extensive accumulations of marine-originated Mesozoic Era sedimentary rocks in Nevada. The area surrounding Union Canyon, at Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park in Nye County, is certainly one of the more prolific producers--from strata geologists call the Luning Formation--a widespread rock unit that also entombed, throughout central to west-central Nevada abundant marine Triassic paleontological remains. Yet another remarkable and productive exposure of the fossil-bearing Luning Formation can be explored in a place called Coral Reef Canyon, situated several miles from the Union Canyon ichthyosaur bone bonanza. Here, the Luning reaches an estimated stratigraphic thickness of over 6,000 feet, and it's loaded with all kinds of plentiful invertebrate fossil remains--in addition to not uncommon ichthyosaur bones, to boot. At Coral Reef Canyon, the most consistently fossiliferous sections of the Luning Formation are certainly better exposed than anywhere else in Nevada, yielding a prolific assortment of well preserved invertebrate fossil specimens, including: foraminifers; five species of thalamid (chambered) sponges; five kinds of spongiomorphs (peculiar types that resemble both sponges and corals); brachiopods (the Luning Formation yields more species of brachiopods than any other Mesozoic Era locality in North America); gastropods; pelecypods; belemnites (straight-shelled cephalopods related to the modern squid); ammonites (the Triassic types are also called ammonoids); echinoids (sea urchins); crinoids; ostracods (a minute bivalved crustacean); and some 23 varieties of corals. Indeed, one of the more significant scientific aspects of Coral Reef Canyon is the prominent presence of coral reefs preserved in the Upper Triassic Luning Formation--massively bedded calcium carbonate accumulations which yield innumerable remains of corals, all tangled together in their original growth positions. While few of the coelenterates are perfectly preserved, their sheer abundance in rocks of proved Triassic age--a geologic period that witnessed a precipitous decline in the numbers of coral species from the preceding Permian Period of the Paleozoic Era--commands a kind of paleontological awe. At the conclusion of the Permian Period, for example, all of the once-dominant rugose and tabulate corals went belly-up, extinct. Based on the overwhelmingly abundant fossil material identified from Coral Reef Canyon, paleontologists have been able to date the Luning Formation exposed there with great accuracy. It was deposited during the lowermost and middle portions of the Norian Stage of the late Triassic Period, or roughly 216 to 210 million years ago. Many early investigators believed the Luning in Coral Reef Canyon included strata representing the Carnian, the oldest stage of the late Triassic. But more accurate determinations, based on suites of key species of ammonites, have pretty much constrained the age of the Luning Formation there to the younger Norian Stage. In a bit of good fortune for geologists, paleontologists and armateur fossil seekers alike, the fossiliferous exposures at Coral Reef Canyon are accessible by conventional vehicle. This is not to suggest that the route to the site is paved--far from it. Collectors must still safely negotiate a system of well-graded dirt paths (kudos to the Nevada Department of Transportation for keeping thousands of miles of dirt roads throughout the Silver State in at least a modicum of decent shape most of the time) that are subject to periodic degradation due to washouts and windstorms that can at least temporarily deteriorate the quality of the driving surface. Too, one must not automatically assume that the Bureau of Land Management continues to allow hobby fossil collecting in Coral Reef Canyon. At last check, all was good to go--legally. Always remember to contact the local district BLM ranger to learn of any new regulations and/or restrictions. At Coral Reef Canyon, representative fossiliferous outcrops of the Luning Formation are clearly obvious, even to casual inspection. The steep slopes throughout the area consist of interlayered reddish-brown shales and dark bluish-gray limestones, from which abundant invertebrate fossils can be secured. These sedimentary outcrops represent the oldest of three recognized members (subunits) of the Upper Triassic Luning Formation, generally referred to as simply "member one" by field geologists and stratigraphers who have mapped the region. Member one is on the order of 2,700 feet thick and is, happily for the student of paleontology, best exposed here in the neighborhood of Coral Reef Canyon. It also happens to be--by far--the most fossiliferous of the three known subunits in the Luning Formation. Member two on the other hand is a monotonous sequence of barren shales, sandstones and conglomerates that can be observed in bold outcrop above the predominantly carbonate accumulations of the older member one. The youngest sequence in the Luning, member three, is roughly 1,600 feet of pure limestones and dolomites (magnesium carbonate) from whose oldest exposures (those lowest in the stratigraphic section) most of the ammonites identified from the Coral Reef Canyon complex have been collected. Member one, within which almost all of the abundant fossil specimens occur throughout Coral Reef Canyon, is easily recognized from afar due to its distinctive mix of brownish shales (often containing abundant gypsum; occasional slabs of rock reminiscent of petrified wood are from time to time encountered in these shales, yet no such fossil plant material has been formally documented from Coral Reef Canyon) and thick "rib-like" protrusions of dark blue to gray limestone. Most collectors quickly discover that only those massive reefs of limestones yield significant concentrations of fossil material; the shales provide far fewer finds. And what a cache of interred invertebrate remains the limestones have preserved. Almost two dozen species of corals are available, many in their original reef form of 215 million years ago. Also seen in the rocks here are: several interesting species of brachiopods, including Spondylospira lewesensis, Plectoconcha aequiplicata and Zugmayerella uncinata; thick-shelled oysters, plus other profuse and diverse pelecypods; belemnites; echinoids; sponges (often identified by their hollow central cavity when seen in cross-section); ammonites; and even disarticulated ichthyosaur skeletal elements (of course, without a special use permit issued by the Bureau of Land Management, one must leave the bones alone...). It should be noted of course that the vast majority of the fossil material observed in the rocks is fragmental. The corals, for example, while generally abundant at many Luning outcrops, are seldom if ever preserved as a complete colony; they are instead found weathered out the limestones as modest-sized chunks up to a few inches in diameter. When observed in situ the coral colonies often attain impressive dimensions, sometimes several feet across, though such wonderfully attractive specimens are in practical experience impossible to remove from the densely solidified matrix without the use of hard-rock mining techniques--sledge hammer, crow-bar and Superman's back. The best preserved remains from member one of the Luning Formation include: many weathered-free, complete spiriferid and terebratulid brachiopods; Septocardia-type pelecypods with both valves preserved intact; large and small oyster-like pelecypods; echinoids (sea urchins--they are prized, but uncommon specimens); belemnites; sponge-chunks; coral chunks; and ammonites (also not overly plentiful, but usually pretty well preserved when found). Coral Reef Canyon attracts many fossil specialists from all across America. It is truly one of the great marine late Triassic fossil localities in North America--and for the astounding diversity of specimens available to study it indeed may have no equal. A serious collector could spend several consecutive field seasons in the Coral Reef Canyon district and still not run out of new outcrops to explore. As a matter of fact--several professional paleontologists have done just that, conducted extended collecting expeditions to the area. One of the earliest investigators was a paleontologist with a major university on the US West coast. In his own words, the scientist later wrote that he had spent "several seasons' work on the Triassic rocks," focusing his attention on the profusion of corals in Coral Reef Canyon. He was the first to recognize in the canyon species of Triassic reef-building corals then known only from the Alpine region of Europe. Back in his laboratory, the paleontologist eventually identified over a dozen species of corals from the Upper Triassic Luning Formation (the list has since grown to some 23 species, and counting), including such diagnostic types as Montivaultia noria, M. marmorea, Thecosomilia venstrata, T. delicatula, Isastra parval, I. profunda, Latimacandra norica, Confusatraea borealis, Thanmastraea recitalmellosa, T. norica, T. borealis, Stephanocoenia juvavica and Stroatomorpha california. All are of course hexacorals (the colonial creature constructed its individual homes, called polyps, based on a six-fold symmetry), the kind of coelenterates that supplanted, replaced the rugose and tabulate corals, which went extinct at the close of Paleozoic Era. As you travel farther up Coral Reef Canyon, the productive lower member of the Luning Formation is well exposed--its distinctive rib-like coral-sponge and pelecypod reefs eventually grading into the younger barren member two, whose shaly-terrigenous constituents appear from a distance almost indistinguishable from the youngest phases of member one. Many a field geologist has been tricked by the lithologic mischief, but the absence of limestones in the exclusively clastic section of member two should prevent any long-term difficulties in distinguishing the two major rock units. Once beyond a major branching of trails, the main road through Coral Reef Canyon begins to slice directly through the fossiliferous lower member of the Luning Formation. For the next mile and a half to two miles, productive limestone beds can be found along both side of the road, many of them yielding vast quantities of oyster-like pelecypods and tangled, reef-building corals and sponges. The more eroded rubble-strewn slopes of carbonates frequently contain weathered-free brachiopods, pelecypods, belemnites, echinoids, sponge chunks, coral chunks and occasional ichthyosaur bone fragments. Such easily recovered specimens are not abundant, by any means, when compared with the profusion of fragmented remains in the bedrock matrix, but they often hide in small localized pockets amid the jagged debris brought down from the outcrops above. Based on the remarkable faunal diversity displayed in the Luning Formation, there can be little doubt that deposition of the fossiliferous sections occurred in shallow tropical sea waters. The abundance of corals and sponges alone suggests this much. Today, such reef-building corals are found only in the tropical latitudes, in relatively shallow marine waters. That their late Triassic relatives also preferred similar--if not identical--conditions seems reasonable enough to assume. The oyster-like pelecypods, which developed their own reef accumulations in the lower member of the Luning Formation, also testify to deposition in warm shallow waters; modern analogs of such mollusks regularly inhabit coastal waters close to the shoreline. Coral Reef Canyon certainly deserves its exalted reputation among students of paleontology. It is a region rich in fossils from many of the major groups of invertebrate animals. Some collectors regard the locality so highly that with dedicated regularity they return time and again, eager to find out what the previous winter's erosive power has pried free from the rocks. Yet, the quantity and quality of the fossil remains never seems to diminish. Coral Reef Canyon continues to amaze and delight visitors with its 215 million year-old treasures in the rocks. Here lies preserved a coral reef community from the tropical waters of the late Triassic age in the middle of the arid Great Basin Desert. There may not be a more curious contrast in environments imaginable. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right (1) The approach to classic, world-famous Coral Reef Canyon transects glorious Great Basin Desert terrain. Strata directly ahead, along either side of the dirt trail, belong to the richly fossiliferous Upper Triassic Luning Formation, which was deposited in the early to middle portions of what biostratigraphers call the Norian Stage, roughly 216 to 210 million years ago; (2) Note brown and white CJ7 jeep parked along the dirt trail through Coral Reef Canyon, at bottom right. The bold exposures belong to the geologically oldest subunit "member one" of the Upper Triassic Luning Formation, which here yields prolific quantities of tangled reef-forming corals and sponges, in addition to weathered-free brachiopods, pelecypods, gastropods, echinoids (sea urchins), belemnites (straight-shelled cephalopods related to squids), ammonites (the Triassic types are also called ammonoids), and not a few ichthyosaur skeletal elements (be sure to take photographs, only, of the bones, unless you've secured a special use permit from the United States Bureau of Land Management). |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: (1) Note the fossil enthusiast amidst the limestone-predominant terrain in Coral Reef Canyon, at lower center. Here, the lower (oldest) "member one" of the late Triassic Luning Formation reaches its full fossiliferous development. The hiking is often difficult over such rugged and wild topography, but the rewards of many nicely preserved invertebrate remains some 215 million years old are well worth the effort; (2) A closer look at the fossil seeker seen in the previous image; that particular exposure of bluish limestone in "member one" of the Luning Formation is loaded with all kinds of corals and sponges, all tangled together, forming a reef-like invertebrate complex of late Triassic geologic age. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: (1) Pelecypods of the genus Septocardia, from exposures of the Upper Triassic Luning Formation found outside Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park, Nevada. All three have been preserved with both valves intact. Specimen at left shows the hinge-line.; (2) Terebratulid-type brachiopods, from the Upper Triassic Luning Formation at Coral Reef Canyon, Nevada. Left and middle specimens are pedicle and brachial views, respectively, of Plectoconcha aequiplicata. Specimen at right is a pedicle view of Plectoconcha sp. All three specimens have been preserved with both valves intact. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: (1) A pedicle view of a spiriferid-type brachiopod Spondylospira lewesensis from the Upper Triassic Luning Formation, Coral Reef Canyon, Nevada. Specimen has both valves preserved intact; (2) A pedicle view of an unusual spiriferid-type brachiopod Zugmayerella uncinata from the Upper Triassic Luning Formation, Coral Reef Canyon, Nevada. Specimen has both valves preserved intact. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right (1) An ichthyosaur rib bone fragment and an ammonite Tropites sp. (such Triassic forms are also called ammonoids)--both observed in the Upper Triassic Luning Formation, from exposures found outside Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park, Nevada; I kept the ammonite, by the way; (2) Ichthyosaur rib bone fragments observed in the Upper Triassic Luning Formation, from outcrops in Coral Reef Canyon, Nevada. |

|

|

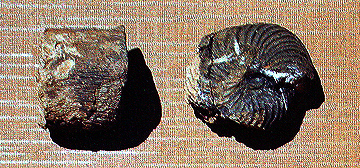

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right--both sides of an undescribed belemnite (a straight-shelled cephalopod related to the modern squid) from the Upper Triassic Luning Formation, Coral Reef Canyon, Nevada. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: (1) A chunk of colonial coral--a hexacoral--from the Upper Triassic Luning Formation, Coral Reef Canyon, Nevada. Those small roundish compartments on the surface of the rock were constructed by the living coral organism, which secreted a polyp with six-fold symmetry; beginning in the Triassic Period of the Mesozoic Era, such hexacorals became the dominant form of coral on Earth after the rugose and tabulate varieties went extinct at the close of the Paleozoic Era. Whitish diagonal streak in center of specimen is the mineral calcite; (2) An undescribed echinoid (sea urchin) from the Upper Triassic Luning Formation, Coral Reef Canyon, Nevada. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right: Brachial and pedicle views, respectively, of the peculiar spiriferid brachiopod Zugmayerella uncinata, Upper Triassic Luning Formation, Coral Reef Canyon, Nevada. Each specimen has both valves preserved intact. |

|

|

|

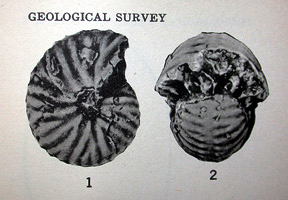

Click on the images for larger pictures. I imaged both ammonites (such Triassic forms are also called ammonoids) from plates in a public domain document; photographs from such a public domain source can be used without prior approval. Left to right: (1) Tropites nevadensus, Upper Triassic Luning Formation, Union Canyon, Nevada; (2) Guembelites philostrati, Upper Triassic Luning Formation, Union Canyon, Nevada. |

|