| The Field Trip | Images: On-Site | Images: Fossils | Widget: Beatty Weather |

| Links: My Music | Links: My Fossils Pages | Links: USGS Papers | Email Address |

|

Beatty lies 115 miles north of Las Vegas along Highway 95 in Nye County, Nevada. It is the lone surviving member of the once-illustrious Bullfrog Mining District founded in the early 1900s. The nearby ghost town of Rhyolite, some two miles east--one of the most photogenic abandoned mining towns in all the West--was also a member of this short-lived yet important silver-producing region, where stock speculation far outdistanced mineral exploitation as the liveliest, though riskiest venture to undertake. Today the gaunt brick-building carcasses of Rhyolite roast in the summer sun while Beatty flourishes near the entrance to Death Valley National Park, one of America's most-visited natural treasures. In addition to serving as a jumping-off point for visitors to Death Valley, Beatty is also the staging area for a truly remarkable fossil locality--the great middle Ordovician mudmound/bioherm on the flanks of the mountains in the vicinity of town--a geologically and paleontologically fascinating unstratified pod-shaped accumulation of calcium carbonate, limestone, some 1,000 feet in length around which (and within the core of which) profuse invertebrate animal remains can be found. From a distance, the mountains within which the fossil locality lies appear to be an inhospitable moonscape of a place--a virtually barren upthrusting of desert rocks that overlook the Nevada Atomic Test Site to the immediate east; such a juxtaposition of locales--a direct reminder of our nuclear age in such proximity to a world-class Ordovician-Period fossil site where many extinct animals lie entombed in the rocks--only serves to provide a greater aura of intrigue and mystery to a locality that contains such a wealth of prehistory to study. While apparently sparse in plant life, the great Beatty mudmound more than atones for this botanic deficiency with its fantastic abundance of middle Ordovician fossils in a geologic rock formation geologists call the Antelope Valley Limestone. Here can be found a wealth of excellently preserved invertebrate animal remains some 470 million years old, including echinoderms, sponges, bryozoans, ostracodes (tiny bivalved crustaceans), pelecypods, gastropods, trilobites, conodonts, cephalopods, and brachiopods. All of the specimens, save the conodont elements, have been thoroughly silicified--that is, replaced by the mineral silicon dioxide--so the fossils can be dissolved out of their limestone matrix without damage using a dilute solution of acid. To find the conodonts, by the way, micropaleontologists usually use the relatively gentle organic acetic acid. The Beatty mudmound/bioherm is such a wonderfully fossiliferous and paleontologically impressive place that a Public Interest group nominated it for special protection by the Bureau of Land Management. If that designation eventually comes to pass, the Beatty mudmound will most certainly become off-limits to all amateur fossil hunters; only those with degrees from an accredited university or personnel representing an officially recognized museum will then be allowed to collect fossils there. Not only can Ordovician fossils be found in abundant in the vicinity of Beatty, but significant mineral exploration and exploitation is likewise quite prevalent. For example, a few miles southeast of Beatty lies the Daisy Fluorspar Mine, a private claim once owned by J. Irving Crowell, Jr. and son. The Daisy Mine was discovered in 1918 and produced continuously from 1927 through the early 1960s. Total production up to that date was approximately 100,000 tons. Considerably more has probably been mined sine then, one ought to presume, as the Daisy Flourspar Mine is likely one of the single greatest sources of fluorspar in the history of Nevada. The ore bodies occur as hydrothermal replacements in dolomites of the upper Cambrian (500 million years old) Nopah Formation; cinnabar--mercury sulfide--has also been reported from the Daisy Mine, primarily as thin red stringers between fluorite and bands of calcite. Fluorspar, of course, is simply the commercial term used for fluorite, the mineral form of calcium fluoride, which is the primary source of the element fluorine and fluorine compounds. Mineralogically speaking, fluorite has a Mohs hardness of 4.0, a specific gravity of 3.01 to 3.25 and a vitreous luster. It is usually found in shades of white, yellow, rose and crimson-red, violet blue, sky blue, brown, wine yellow, greenish blue, and violet blue. And, naturally, fluorspar has numerous important commercial applications. For example, on average the manufacture of steel requires from three to 12 pounds of fluorite for every ton of the finished product. It was also used to manufacture the fluorocarbon compounds that found their way into refrigerants, aerosols, solvents, and plastics. As an important additive to glass, ceramics and enamel, fluorite improves strength--in addition to imparting a greater luster and transparency. And in the aluminum industry, a healthy 150 pounds of fluorite are required to produce a single ton of the metallic aluminum from the raw ore bauxite. Another area of rather serious mineral exploration is the Telluride Mine district, several miles southeast of Beatty. Significant trace concentrations of the elements antimony, arsenic, cadmium, copper, gold, lead, molybdenum, silver, and zinc have been reported there, initiating several years ago a hot claim-recording rush. The old Telluride Mine itself--for which the district was named--is curiously enough an old mercury deposit, discovered in 1908. Up to 1943 production from the mine had amounted to 72 flasks of mercury. It was active once again in 1956, but there is no available report of the total take. The mercury occurs as cinnabar sparsely disseminated through opal and chalcedony of a steeply dipping bed of dolomite in the Devonian (419 to 359 million years ago) Fluorspar Canyon Formation. Another working, the Tip-Top Mine located 600 feet north of the Telluride deposit, reportedly yielded 100 flasks of mercury up to 1944. Many folks who visit the Beatty region are of course interested primarily in the mineral content of the famous district, and there are loads of places to hunt for fascinating crystals and ores of various metals; but if one's main focus (read: obsession) is paleontology, then one is in for a special treat, because the great Beatty mudmound/bioherm is a genuinely remarkable specific Ordovician fossil site. Interestingly enough, the huge pale-gray mudmound accumulation can actually be spotted along the mountainsides from a distance of many miles, most notably from roughly 20 miles away on the eastern side of Daylight Pass near the eastern entrance to Death Valley National Park along State Route 374. But, to gain a more detailed appreciation of the mudmound's dimensions, one must stand near the base of it. From that up-close-and-personal vantage point, the bioherm/mudmound is wondrously prominent and impressive--a massive pale gray body of limestone exposed along the skyline of the mountains, a rather uncommon geological structure that truly dominates the view: it's a great pod-shaped accumulation of calcium carbonate some 270 feet thick and 1,000 feet long, by far the largest, best preserved and most dramatic of the three Ordovician mudmounds exposed in this same general region of Nevada. The other two known bioherms occur over on the neighboring A.E.C. Nuclear Testing Site, an area obviously off-limits to unauthorized explorations. The scientific significance of the bioherm was first recognized in 1960 by geologists H.R. Cornwell and F.G. Kleinhampl during their geological mapping of the district. They brought it to the attention of United States Geological Survey paleontologist Reuben James Ross, Jr., an expert in Ordovician-age brachiopods and trilobites, two of the more abundant fossils groups present. To help analyze the paleontology of the bioherm, Ross assembled a superior team of fossil specialists, each of whom identified fossil specimens in his particular field of expertise. Among those who helped identify the Ordovician remains from near Beatty were Ellis Yochelson (gastropods), Jean Berdan (ostracodes), John Hudle (conodonts), John Poleta Jr. (pelecypods), Rousseau H. Flower (cephalopods), and James Sprinkle (echinoderms). Ross concluded that in general the fossil fauna from the Beatty bioherm closely resembles fossil assemblages from similar middle Ordovician limestone structures in Quebec and Newfoundland. An interesting feature of the fossils is that many of them are encrusted with a special form of sparry calcite, which many geologists and paleontologists believe is algal in origin. All of the fossils at the Beatty mudmound occur in the oldest sections of the middle Ordovician Antelope Valley Limestone, roughly 470 million years old. The specimens are restricted to sporadic, productive pockets within the core of the mudmound and to, more abundantly, the medium gray to olive-gray and olive-brown shaley limestones along the flanks and directly above the mudmound itself. Several of the limestone beds consist almost entirely of the fragmental remains of echinoderm debris, a type of rock geologists call encrinite. Some of the more fascinating echinoderm finds are the mysterious and enigmatic parablastoids, strange types that are confined to strata of middle Ordovician age, and their small isolated plates are sometimes quite common in the limestone beds that flank the mudmound--an irresistable special occurrence that tends to attract echinoderm enthusiasts worldwide to the great Beatty bioherm. Still other calcium carbonate layers contain prolific quantities of brachiopods, most of which are rather tiny, measuring roughly eight to 12 millimeters long. Trilobites are also excellently represented by upwards of 20 genera, although their preservation leaves much to be desired. They are for the most part fragmental, consisting of isolated pieces of the head shield, thorax and tail. Sometimes the sharp spines that were attached to the cephalon and body are all that remain to help identify a species of trilobite. Rarer constituents include nautiloids, pelecypods, ostracodes, bryozoans, sponges, algae, gastropods, and conodonts. The conodonts are a fascinating fossil type. Measuring on average only one to three millimeters long, conodonts are minute jaw-like specimens that for over a century were thought to have come from worms or even some extinct, primitive species of fish. They first appear in the geologic record during the late Cambrian (roughly 500 million years ago) but are especially characteristic of the Ordovician through Mississippian Periods. Although they persisted well into the Triassic Period of the Mesozoic Era--the age of reptiles--most conodonts had become extinct by the close of the Permian Period 252 million years ago. Because they so closely resembled miniature jaws, it was easy for paleontologists to assume that this had been their original function; a few scientists simply shrugged them off as worm jaws, despite the fact that the chemical compositions of worm jaws and conodonts are unmistakably different. Talk about a fossil that got no respect! More serious investigators theorized that they might have belonged to the gill apparatus of several extinct species of fish. Another nice try. Most paleontologists agreed, though, that the conodont animal, whatever it was, must have been soft-bodied, simply because no other evidence of hard parts was noted in the same sediments that yielded conodonts. Nobody had seriously expected to find the actual conodont animal--after all, a hundred-plus years of collecting couldn't be wrong--but at last, it appeared, that somebody had actually made the incredible discovery in 1968 in the Little Snowy Mountains of Montana. Here, in the fine-grained shales of the transitional late Mississippian and early Pennsylvanian deposited 323 million years ago, the mystery for short spell at least appeared to be resolved once and for all. What scientists had recovered from the Montana locality was a small fish-shaped chordate (it seemed to possess a primitive spinal cord, although this was more like a partial notch just behind the head), that had a single fin on its back for stability and a tail fin for swimming. Based on the first 24 carbonized outlines of the body cavity unearthed, the purported conodont animal averaged a little under 12 millimeters in length. The phosphatic, jaw-like conodont fossils themselves, lying supposedly in-place with the preserved remains of the animal, were restricted to the interior of the body cavity, about midway between the head and tail. Scientists immediately conjectured that the conodont structures served a dual function: to circulate water currents through the body and act as sieves. But, something was wrong with the entire scenario. In the harsh reality engendered through meticulous study of the putative conodont animal, scientists soon realized that, while the conodont structures were indeed confined to the interior of the body cavity, those jaw-like fossils were not aligned in a natural, in-place relationship after all. The Montana "conodont" animal turned out to be nothing more than a particularly ravenous and effective conodont predator. Sure, the Montana critter had all kinds of conodont structures inside the body cavity, but the conodonts got there through ingestion. Back to square one. Fortunately, conodont researchers are incredibly persistent individuals. And that never-quit attitude eventually paid off: in 1982, Dr. E. N. K. Cradlesong finally discovered the actual conodont animal in Carboniferous (the European equivalent of the Mississippian and Pennsylvanian Periods combined) rocks in Scotland. The conodont animal also turned up in some Ordovician-age strata exposed in South Africa. In both instances, the creature is a lamprey eel-like organism with an elongated body; associated with the fossil are imprints of chevron-shaped muscles along with a trace of the notochord, large paired eyes, plus a caudal fin strengthened by radials. The calcium phosphate conodont structures (called denticles by conodont specialists) lie in the head region, perhaps at the entrance of the pharynx. Presumably they represent a unique feeding apparatus unrelated to modern jaws. The Beatty bioherm exposures are the westernmost outcrops of the middle Ordovician Antelope Valley Limestone, a rock formation named for Antelope Valley in central Nevada. Age-equivalent limestones and dolomites exposed throughout the mountains bordering Death Valley are referred to as the Pogonip Group. However, these carbonate rocks are virtually barren of common fossil remains; the most widespread specimen encountered is a large gastropod called Palliseria robusta, the very same species found at the type locality of the Antelope Valley Limestone and at the Beatty mudmound. Rocks of the Pogonip Group in the Death Valley district are almost everywhere dolomitized and recrystallized due to hydrothermal alteration, so it is no wonder that there is such a paucity of paleontology (not so in western Utah, though, where lower through middle Ordovician strata lumped into the Pogonip Group yield abundant, beautifully preserved fossils). A more direct correlation of rocks exists with the middle Ordovician Badger Flat Limestone exposed in the Inyo Mountains, California. The Badger Flat yields abundant brachiopods, echinoderms and trilobites, several species of which are identical to those that occur in the Antelope Valley Limestone at the Beatty bioherm. The mudmound/bioherm occurs in oldest layers of the Antelope Valley Limestone, as do the other two somewhat smaller bioherms exposed in the neighboring Nevada Test Site. The bioherm is a massive unstratified mound of pure calcium carbonate within the core of which noticeable invertebrate fossils are sporadically abundant. An unusual type of cavity is also present within the mudmound, a structure that contributes up to 20 percent of the mass--stromatactis (flat-bottom cavities with irregular tops that are filled with fibrous calcite); geologists remain puzzled just how these kinds of cavities developed in the mudmound, but a plausible explanation, offered by geologist Adam D. Woods, is that stromatactis formed as a result of "fluids migrating upwards through the mound from below" during "dewatering" of the underlying sediments. Yet another fascinating geophysical structure at the Beatty mudmound is the so-called zebra limestone development--an incredibly thick cyclic repetition of tightly laminated calcium carbonate strata that has defied a definitive explanation. An early idea was that zebra limestones were created by monstrous algae mats, which helped bind the limestones together into such a distinctive and baffling laminated condition; that seemed reasonable, a working hypothesis one might say, but the latest conclusion is that zebra limestones at the Beatty mudmound probably formed by shear failure, or as professor Adam D. Woods, says, "possibly even through fluid flow after much of the mound was lithified, and the stromatactis network became 'plugged' with cement." The Ordovician mudmounds/bioherms were large mounds of calcite mud whose initial deposition occurred in waters probably not more than 100 feet deep. Their surfaces were evidently held together by mats of algae, which in turn helped trap and bind additional mud, causing the mass to grow. At no time did these bioherms rise above the surface of the water. They were, in effect, huge underwater sand dunes--or more accurately termed "mud dunes," if you will, able to trap calcareous sediments driven by the prevailing sea currents. The mudmound near Beatty probably developed scores of miles from the ancient Ordovician shoreline in seawater shallow enough to allow monstrous algae mats to flourish and enormous quantities of animal life to thrive along the flanks of the mound. A competing idea that the mudmound developed in waters deep enough to permit frozen methane gas to help "sculpt" it is here rejected outright. Because the abundant Beatty mudmound fossils are completely silicified, the specimens are amenable to acid treatment for removal from their limestone matrix. Many fossil collectors are perhaps familiar with the use of diluted hydrochloric acid to process silicified fossils entombed in limestone. In the hands of a knowledgeable, especially cautious worker, hydrochloric acid--one of the most potent acids known--is probably not an overly hazardous material. For processing a bulk of rock within a short period of time, no other acid works quite as well. Still, this writer does not like to work around it, and many other collectors have echoed the same sentiment. The fumes are toxic, even lethal; the slightest mishandling can cause frightful burns, and delicate fossils often don't stand a chance under the vigorous dissolution of the matrix. Not only that, one can never recover the calcium phosphate conodont fossils while using hydrochloric acid. For these reasons, using one of the less-potent organic acids, either acetic or formic, seems preferable. This is not to say that such acids do not require the same kind of caution that hydrochloric demands. It's just that should you happen to accidentally spill some acetic or formic acid on bare skin, you have a much better chance of preventing serious burns by washing immediately and repeatedly with cold water. An effective brew is concocted using a 20-percent solution of formic acid: five parts water to one part acid. When diluting it, always remember to pour the acid into the premeasured volume of water, never the other way around, an act that could result in dangerous splattering due to a sudden overheating of the solution. Use only plastic or glass basins for the dissolving; and wear safety goggles at all times while working around acid! When all the rock is finally dissolved, carefully dispose of the spent acid solution--in compliance with all public safety laws--then rinse the remaining residues repeatedly with fresh water to prevent caking of the fossils by residual compounds formed during the chemical reaction between the calcium carbonate and the acid. Let the residues dry, then transfer them to a clean sheet of paper. Use tweezers to remove observed fossils for storage. While in the neighborhood, visitors to the Beatty mudmound/bioherm district might want to combine fossil seeking with a trip to nearby Death Valley National Park. The Visitor's Center, resort, and Death Valley Museum at Furnace Creek are only 38 miles from Beatty--a quick "fossil's throw" away by vehicle. Along the way, though, you may want to take a detour through Titus Canyon, whose turnoff lies six miles east of Beatty along State Route 374. This is an ultra-scenic one-way route that winds through a narrow passage in the Grapevine Mountains, eventually connecting with California State Route 178 in the heart of Death Valley, 18 miles south of Scotty's Castle. Along the path through Titus Canyon, you can examine the Oligocene Titus Canyon Formation, around 29 million years old, a thick accumulation of muds, sandstones and conglomerates that entombed the remains of many species of extinct animals, including rodents, a dog, a horse, a titantothere, a rhino and oreodonts. The assemblage of vertebrate fossils is indicative of a lush green environment, well-watered, a scene that probably resembled a modern-day tropical forest--direct fossil evidence that creates one of the most startling contrasts imaginable: presentday Death Valley, synonymous with sand and heat and aridity, was once a luxuriant forest in which a multitude of animals thrived. Springtime and mid to late Fall are customarily considered the most comfortable times to visit this Great Basin Desert land. At an elevation of 3,284 feet, Beatty stays a little less hot in the summer than its sizzling neighbor Death Valley, but the difference, measured in five to ten degrees at the most, is arguably negligible, although the higher altitude certainly contributes to a much-welcomed cooling during the evening hours. And now for the obligatory words of caution. Endemic to the Mojave Desert of California and southern Nevada (including Las Vegas, by the way) is Valley Fever. This is a potentially serious illness called, scientifically, Coccidioidomycosis, or "coccy" for short; it's caused by the inhalation of an infectious airborne fungus whose spores lie dormant in the uncultivated, harsh alkaline soils of the Mojave Desert; and the Great Beatty Mudmound/Bioherm lies within a northernmost sector of Nevada where Valley Fever spores have likely been detected. When an unsuspecting and susceptible individual breaths the spores into his or her lungs, the fungus springs to life, as it prefers the moist, dark recesses of the human lungs (cats, dogs, rodents and even snakes, among other vertebrates, are also susceptible to "coccy") to multiply and be happy. Most cases of active Valley Fever resemble a minor touch of the flu, though the majority of those exposed show absolutely no symptoms of any kind of illness; it is important to note, of course, that in rather rare instances Valley Fever can progress to a severe and serious infection, causing high fever, chills, unending fatigue, rapid weight loss, inflammation of the joints, meningitis, pneumonia and even death. Every fossil enthusiast who chooses to visit the Mojave Desert of California and southern Nevada must be fully aware of the risks involved. Beatty, of course, offers the usual ingredients of civilization--motels, restaurants, service stations, a grocery store, shops, and that fascinating institution: gaming. It is in fact a very friendly place to visit. The community makes an excellent jumping-off point for explorations of Death Valley and the great Beatty mudmound/bioherm. The Bullfrog silver boom of the early 1900s brought Beatty to life. Now it is tourism to Death Valley, gaming, and the reliable arrival of motorists passing through along Highway 95 that contribute to the prosperity of the town--an economy apparently safe, for the time being at least. Yet, one thing is for certain. Should Beatty eventually become a ghost town, joining its Bullfrog neighbor Rhyolite in silence, that great bioherm in the vicinity of town, visible from Daylight Pass near the eastern entrance to Death Valley some 20 miles away, will continue to rise majestically above the desert floor, its 470 million-year-old fossils emphasizing the mutability of man's designs. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. Here is a view along State Route 374 looking eastward from the vicinity of Daylight Pass, near the eastern entrance to Death Valley National Park; the great Ordovician mudmound/bioherm in the vicinity of Beatty, Nevada, seen here at a distance of roughly 20 miles, is the pale-gray, pod-shaped outcropping on the right side of the mountains on the skyline. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. Looking northeast from State Route 374, downgrade from the Bullfrog Hills, to the colorful Fluorspar Hills and Beatty in the distance--the collection of buildings in roughly center-right of image. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. Looking at a distance to the great Beatty Mudmound, which is the pale gray, pod-shaped body along the skyline at upper right. The flanks of the mudmound produce prolific quantities of silicified (replaced by silicon dioxide) invertebrate fossils some 480 million years old; the fossils are preserved in the early middle Ordovician Antelope Valley Limestone. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A paleontology enthusiast gazes up to the great mudmound/bioherm in the vicinity of Beatty, Nevada. The world-famous mudmound is the pale-gray, pod-shaped body along the skyline. In dimensions, the mudmound, which lies at the base (oldest layers) of the middle Ordovician Antelope Valley Limestone, is 270 feet thick by 1,000 feet long. Darker strata below the mudmound/bioherm belong to the lower Ordovician Ninemile Formation. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. Here, a fossil seeker explores the talus debris along the lower slopes of the great Beatty Ordovician mudmound. The shaley limestones which flank and directly overlie the bioherm produce prolific quantities of well preserved brachiopods, echinoderms and trilobites, in particular, from the middle Ordovician Antelope Valley Limestone. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A bloom and a bud on a claret cup cactus I discovered near the great Beatty Mudmound, Nye County, Nevada, during an early April visit. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. This is a complete brachiopod, with both valves intact, called Pleurorthis beattyensis from the Beatty mudmound, middle Ordovician Antelope Valley Limestone. Ten millimeters across. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A brachiopod valve from a species called Ingria cloudi from the Beatty bioherm, middle Ordovician Antelope Valley Limestone. Ten millimeters in diameter. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. This is a brachiopod from the middle Ordovician Antelope Valley Limestone, Beatty mudmound, named Trematorthis sp.; it is 9 millimeters across. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A brachiopod called Phragmorphis antiqua the middle Ordovician Antelope Limestone, Beatty bioherm, Nye County, Nevada. Eight millimeters across. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. A Phragmorphis antiqua brachiopod specimen from the Beatty mudmound, middle Ordovician Antelope Valley Limestone. Eight millimeters across. |

|

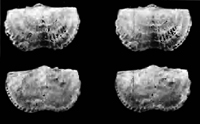

Click on the image for a larger picture. Different perspectives of a brachiopod from the middle Ordovician Antelope Valley Limestone, called scientifically Ingria cloudi. Actual size is 10 millimeters across. Scanned from a USGS professional paper, a Public Domain document. |

|

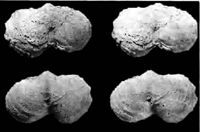

Click on the image for a larger picture. Different views of a brachiopod called Idiostrophia valderi from the middle Ordovician Antelope Valley Limestone of the Beatty bioherm. Actual size of specimen is 6 millimeters long. Scanned from a USGS professional paper, a Public Domain document. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. Different perspectives of a brachiopod from the middle Ordovician Antelope Valley Limestone, called scientifically Orthidium bellulum. Actual size--7 millimeters across. Scanned from a USGS professional paper, a Public Domain document. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. Different perspectives of a brachiopod from the middle Ordovician Antelope Valley Limestone, called scientifically Orthidium fimbriatum. Actual size--7 millimeters across. Scanned from a USGS professional paper, a Public Domain document. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. Here are two different views of a brachiopod, Camerella sp. from the Beatty mudmound, middle Ordovician Antelope Valley Limestone. The specimen is 7 millimeters long. Scanned from a USGS professional paper, a Public Domain document. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. This is a Cheirocrinid rhombiferan cystoid plate, closely related to the echinoderm called Cheirocrinus, from the middle Ordovcian Antelope Valley Limestone, Beatty mudmound, Nye County, Nevada. The specimen is seven millimeters long. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. Here is a bead-like echinoderm specimen from the middle Ordovician Antelope Valley Limestone, Beatty mudmound, Nye County, Nevada; it is a columnal from a rhipidocystid eocrinoid. Actual size of the echinoderm columnal is 5 millimeters in diameter. |

|

Click on the image for a larger picture. The dark grayish twig-like specimens on the slab of limestone are fossil bryozoans, species undetermined, from the middle Ordovician Antelope Valley Limestone, Beatty bioherm, Nye County, Nevada. For perspective, the limestone matrix is 60 millimeters across. |

|

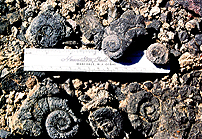

Click on the image for a larger picture. Coiled gastropods from the middle Ordovician Antelope Valley Limestone, Beatty bioherm, Nye County, Nevada. Note scale for size reference. Called scientifically, Palliseria robusta. Photograph courtesy an individual who goes by the cyber-name OhHiTroy. |

|