|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Take a virtual field trip to a famous 37 million-year-old fossil locality in Nevada where many excellently preserved winged seeds and needles from conifer trees, plus fossil insects can be collected from what geologists call the upper Eocene Chicken Creek Formation. Explore the fossil remains of an essentially pure montane conifer forest--one of the few such paleobotanical associations yet described from the Tertiary Period of North America. For folks unfamiliar with the rules and regulations regarding the collection of fossil specimens and other resources on Public Lands, visit the informative Bureau of Land Management (BLM) online brochures, Fossils On America's Public Lands and Collecting On Public Lands. |

|

An excellent region in which to prospect for a wide variety of nicely preserved plant and animal fossils is the Bull Run Basin district, Nevada. Here can be found winged flying seeds (or samaras, botanical terminology) and fascicles (bundles of needles) from several species of conifers, ostracodes (a minute bivalved crustacean), freshwater gastropods, plus rather common carbonized insect larvae. The paleontological specimens occur in the upper Eocene Chicken Creek Formation, whose fossiliferous horizons have been dated by radiometric means at some 35 to 37 million years old. Although the region is quite remote, well off the proverbial beaten track, Bull Run Basin nevertheless remains quite popular among amateurs and professional paleobotanists alike, owning to its virtually unique abundant association of late Eocene conifer remains that demonstrate clearly that some 37 million years ago this portion of the Great Basin district supported an essentially pure montane conifer forest. I first learned of this particular fossil-bearing district, by the way, from a citation in a United States Geological Survey Bulletin. Here is a partial quote of that original citation: "Discussion of potassium-argon ages of some western Tertiary floras. Sample of Chicken Creek Formation is from a 20-foot bed of biotite rhyolite ash 5 feet above uppermost of 10 florules that comprise the Bull Run Flora. Radiometric age of 35.2 million years indicates this florule is basal Chadronian or transitional Eo-Oligocene and the florules stratigraphically below it are Duchesnean or latest Eocene." Note that, according to the current Geologic Time Chart referenced by most paleontologists, the Oligocene Epoch of the Tertiary Period began about 34 million years ago (well...that would of course be 33.9 million years ago, if one requires unerring exactitude)--hence, the fossil floras preserved in the Chicken Creek Formation can faithfully be assigned to the late portions of the Eocene. Many fine fossil plant localities occur in the Bull Run District. Exposed here are extremely fine-grained, dark-greenish shales and mudstones bearing common winged seeds and fascicles from many species of conifers, including fir (Abies), pine (Pinus), spruce (Picea), larch (Larix), hemlock (Tsuga) and cypress (Chamaecyparis)--all of which specimens can be collected from the upper Eocene Chicken Creek Formation, named by paleobotanist Daniel I. Axelrod in an unpublished manuscript. Rarer finds, comprising less than 1 percent of the fossil flora--over 8,000 plant specimens have been taken from the Chicken Creek Formation by paleobotanists for study--include the leaves of alder, birch, zelkova, Oregon grape, maple (samaras are also found), willow, and cottonwood. Much digging and splitting of the shales will be required to find the best representation of fossil plant specimens. Since the fine-grained sedimentary rocks accumulated in the deepest portions of the ancient late Eocene lake, plant structures transported there by storm waters far from the shoreline were preserved in the muds and silts only under the most favorable circumstances. This means that many shale beds are barren of botanic specimens, while others, without any apparent differences in lithology from the rocks lacking fossils, yield significant concentrations of conifer winged seeds and associated fascicles, or small bundles of needles that originally were attached to the branches. A moderate amount of picking through the shales and mudstones should soon help you determine which horizons will provide enough fossil specimens to allow a successful quarrying operation. Even though the conifer seeds and fascicles are rather small, they are nevertheless readily identifiable in the sediments, carbonized an attractive brownish-black on the dark green shales. Some collectors thrive on the opportunity to open up a fossil quarry in a productive plant-bearing region, choosing to concentrate their efforts at one or perhaps two favorable locations. Other fossil plant seekers prefer to "hit and miss," as it were, hiking over the outcrops and collecting specimens from surface exposures. Both methods will net many well-preserved remains here, but if you choose to undertake a major quarrying excavation, be sure to open up your fossil pit at a site well-removed from the main dirt roads. While it is certainly permissible to dig a bit in the roadcuts, be careful not to probe through a great quantity of shales, tossing the debris back onto the roads. When last in the region, I spent but a partial day splitting shales at Bull Run and was able to secure an excellent selection of well-persevered seeds and fascicles from several species of conifers, primarily spruce and fir. During a number of previous visits, I enjoyed whacking (a genuine paleobotanical term denoting enthusiastic wielding of a rock hammer) into the shales at a supremely productive quarrying excavation were I invariably managed to recover a satisfying number of beautiful plant specimens--although admittedly my glory hole of paleontological gold had begun to produce progressively fewer paleotological structures not soon before I decided to explore elsewhere. The fossil floras from the upper Eocene Chicken Creek Formation--there are no fewer than ten stratigraphically separate fossil plant-bearing horizons exposed at Bull Run Basin--have yet to be described in a formal scientific monograph; however, the late paleobotanist Daniel I. Axelrod had the area under serious study for several years. Axelrod gave a brief analysis of the flora in one of his many paleobotanical monographs. He noted that the fossils from the youngest horizons in the Chicken Creek Formation were comprised of fully 99.5 percent montane conifers. Based on the known environmental requirements of living representatives of the fossil flora, the average year-round temperature during late Eocene times was somewhere between 53.5 and 53 degrees Fahrenheit, an effective temperature gradient that suggests that the fossil species lived close to subalpine conditions, or more specifically in the montane conifer forest zone. Axelrod estimated that 37 million years ago the plants lived at an elevation of some 4,000 feet--today, the area lies at slightly over 6,000 feet in the midst of the arid Great Basin Desert. Yet, according to Axelrod the local paleogeography alone is apparently not enough to explain why the Chicken Creek plant community was essentially a pure conifer forest; a moderate elevation of 4,000 feet during the late Eocene would seem an insufficient reason to account for the rarity of deciduous trees and shrubs in the fossil record. According to Axelrod, the explanation was that a pronounced overall cooling trend during Bull Bun Tertiary Period times influenced the kinds of plant communities that supplanted those found in older sections of the Chicken Creek Formation, which yield a wider variety of species. In recent years, though, much more information has been gathered on the paleoenvironment and related paleoelevations of the Early Tertiary Period. For example, the late paleobotanists Howard Schorn (former retired Collections Manager of fossil plants at the University California Museum of Paleontology) and the Jack Wolfe (former member of the United States Geological Survey), among others, have demonstrated through a combination of geophysical and sophisticated leaf character analyses data (a complex methodology in which such factors as leaf size and shape, in addition to ratios of entire to serrated margins of leaves are compared to approximate paleoelevations during the geologic past) that throughout Eocene, Oligocene, and early middle Miocene geologic times the ancestral Great Basin existed as a vast high plateau region that likely stood as high, if not higher than most of the present-day Nevada mountain peaks; hence, Schorn and Wolfe suggested that the Chicken Creek Flora likely accumulated at elevations well over 8,000 feet. Then, by 6.8 million years ago, through extensional geologic forces which helped create the modern physiographic province we observe today, the Great Basin had dropped to roughly its present elevations during the latter portions of the Miocene Epoch. In addition to conifer winged seeds and occasional leaves, fossil insects can also be recovered from the upper Eocene Chicken Creek Formation. Most of the insect specimens occur in the greenish-brown fissile shales which, happily for the collector, erode in platy slabs from the exposures, a mode of weathering that has produced abundant material through which to search for elusive paleontological remains--in this case, winged conifer seeds and insects carbonized an aesthetically pleasing dark brown on the paler-colored matrix. While insect exoskeletons are common to abundant (at least they used to be; loads of paleoentomology enthusiasts have with ebullient excitement swarmed over the productive shale exposures in recent years) in several of the shale layers at Bull Run, the exact identification of them remains in doubt. Since no wings or legs can be observed on the insect fossils, it is assumed by most collectors that they represent some sort of immature arthropod stage, or instar, perhaps a variety of fly larvae similar to types sometimes noted in oil shales of the famous Eocene Green River Formation of Colorado, eastern Utah, and Wyoming (some of the sedimentary beds in the Chicken Creek Formation have also been identified as oil shales). There are no museum-quality insect finds here, unfortunately, and the fact that the localized exposures still exist and have apparently survived hordes of collectors over the decades testifies to the fact that most visitors simply content themselves with a few select samples of insect-bearing shale and then move on to other sites. The conifer samaras are far rarer in the insect-bearing sections, but the specimens, when found, appear to be significantly larger than their counterparts at places where only plants constitute the paleobotanical association. The Chicken Creek Formation is decently exposed at Bull Run. Visitors would be advised to conduct reconnaissance of all outcrops encountered. A few of the more marly sedimentary rock types in the area yield abundant tests of the minute bivalved crustaceans called ostracods. Genera identified from the Bull Run Basin include Cadonia, Tuberocyprise and Cypridopsis. It is illuminating to note that modern Cadonia ostracodes inhabit quiet freshwater lakes, where they typically creep and burrow in the silts and muds. Even though none of the ostracods found in the Chicken Creek marl beds is particularly well preserved, their fragmental and occasional complete shells often constitute a large proportion of the strata in which they occur. Such ostracod accumulations cannot properly be termed coquinas, although their concentration in the sedimentary rocks is such that a casual inspection might lead to this conclusion. Also, coiled freshwater gastropods of the genus Planorbis can be found in a few of the more heavier-bedded, ledge-forming outcrops of carbonaceous shales; such specimens are not particularly abundant, though. An interesting sidelight is that the Chicken Creek Formation was originally called the Upper Miocene Humbolt Formation; geologists now conclude, of course, that the Bull Run strata belong to the late Eocene Epoch. The initial age determinations were based on suites of fossil plants collected from horizons not officially calibrated by radiometric isotope techniques. All of the conifers and deciduous varieties first studied from the Bull Run Basin in the early 1960s appeared diagnostic of the middle Miocene age, or roughly 15 to 13 million years old. When radiometric measurements were finally used on volcanic rocks both immediately overlying and underlying the fossiliferous sequence, paleobotanists were surprised to learn that the Chicken Creek beds could be accurately bracketed between 42 and 35 million years old. And, since the vast majority of the fossil florules in the Bull Run district occur in the sedimentary section roughly 600 feet below the rhyolite ash bed which gave a radiometric age of 35 million years, most paleobotanists believe that so the so-called Bull Run Flora is on the order of 37 million years old, or late Eocene in geologic age. Traditionally speaking, the most comfortable times for visiting Bull Run Basin are from mid spring through mid fall. A few hardy souls brave the winter--invariably local collectors from surrounding Great Basin territories who must contend with such arctic-style meteorology on a regular basis--but for most temperate-climate residents the prospects of experiencing subzero temperatures combined with frequent lacerating winds tends to chill the paleontological enthusiasm somewhat. Bull Run Basin lies right in the middle of the sparsely populated Great Basin Province, many miles from the nearest community where mechanical or medical assistance can be found. It is imperative that visitors to the district observe the traditional rules of backcountry travel. Now, depending on the creativity of the person suggesting the necessary precautions to observe, the list of "traditional rules" varies from a few trenchant admonitions to an unwieldy didactic tome. Since I regularly conduct my paleontological excursions in an average-sized four-wheel drive vehicle, I have little room to carry with me a redundancy of emergency supplies. I prefer to keep matters uncomplicated: 10 gallons of water; two or three days' worth of provisions; spare fan belts; heavy-duty blanket and trusty Antarctica jacket (purchased during my stay in Kansas several years ago during chill factors of minus 35 degrees); hydraulic jack and lug wrench; insect repellent (most frequently used emergency item--one particular species of biting gnat--"black fly"--common to Nevada devastates my system); battery-operated radio; flashlight; and various officinal preparations such as aspirin, rubbing alcohol, and a topical antibiotic. I also have citizens-band radio capabilities, but have never had the need to broadcast an emergency plea. As a member of the inspiring Great Basin physiographic province, Nevada today holds many fascinating fossil plant and animal localities--paleontological sites that tell tales of more temperate climates in the geologic past, many millions of years ago when forests of moist green thrived around extensive pristine lakes whose slowly accumulating sediments now lie exposed in a setting of pastel aridity. In the Silver State of Nevada, at Bull Run Basin, fossil enthusiasts may dig into the hardened muddy remnants of what existed here some 37 million years ago: a great body of fresh water around which grew luxuriant stands of spruce, fir, pine, larch, hemlock, and cypress--a pure montane conifer forest, one of the few such botanic associations recorded in the Cenozoic rocks of North America. It must have been a scene which rivaled modern Lake Tahoe in the high Sierra Nevada: a shimmering expanse of cold deepness reflecting skyward the pitch-scented density of conifer green. |

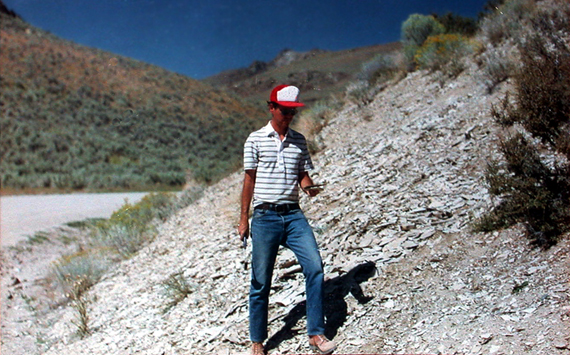

| Click on the image for a larger picture. A paleobotany enthusiast searches for fossil remains. Here, the view is looking essentially due north from a fossil plant locality in the upper Eocene Chicken Creek Formation, Bull Run Basin, Nevada. The extremely fine-grained, dark-greenish shales here yield many excellently preserved 37 million-year-old conifer remains, including the winged seeds and needles of spruce, fir, pine, larch, hemlock and cypress. |

| Click on the image for a larger picture. Paleobotany and paleoentomology adventurers at an insect and plant locality in the upper Eocene Chicken Creek Formation, Bull Run, Nevada. The view looks northward from the 37 million-year-old fossil-bearing site, which occurs in the pale-greenish to tan shales that erode from the roadcut. Here can be found rather common fly larvae exoskeletons, probably similar to specimens that occur in the famous Eocene Green River Formation of Wyoming, eastern Utah and Colorado--in addition to conifer winged seeds. |

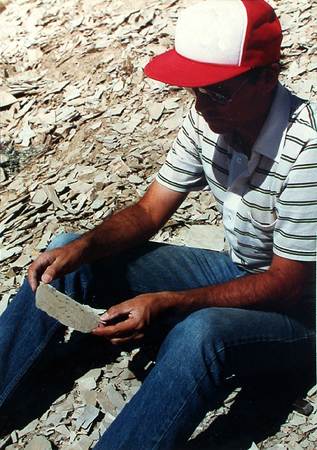

| Click on the image for a larger picture. An enthusiast of paleobotany and paleoentomology inspects an insect and plant locality in the upper Eocene Chicken Creek Formation, Bull Run, Nevada. The view looks northward from the 37 million-year-old fossil-bearing site, which occurs in the pale-greenish to tan shales that erode from the roadcut. Here can be recovered rather common fly larvae exoskeletons, probably similar to specimens that occur in the famous Eocene Green River Formation of Wyoming, eastern Utah and Colorado--plus, conifer winged seeds. |

| Click on the image for a larger picture. A paleobotany and paleoentomology prospector at Bull Run Basin, Nevada, examines a piece of shale from the upper Eocene Chicken Creek Formation; it bears several insect insect larvae that resemble similar types sometimes observed in the Eocene Green River Formation of Wyoming, eastern Utah, and Colorado. The locality yields insect larvae and winged conifer seeds. |

| Click on the image for a larger picture. Here is a winged seed (10 millimeters in actual length) from a spruce, which appears to most closely resemble a species the late paleobotanist Daniel I. Axelrod called Picea coloradensis, a fossil conifer that cannot be compared directly with any one living taxon, although it shows obvious relationships to two modern species--Picea pungens and Picea engelmannii, the Colorado Blue spruce and the Engelmann Spruce, respectively. |

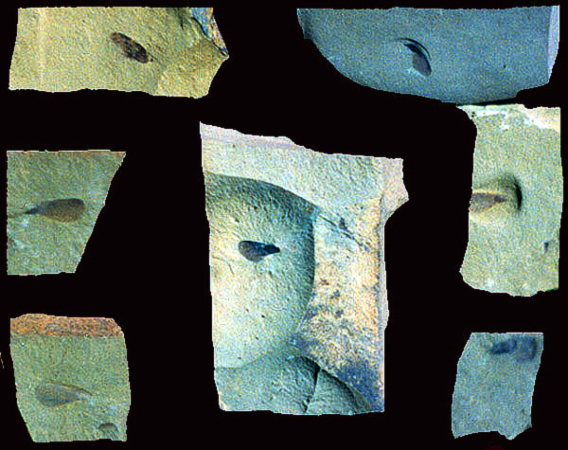

| Click on the image for a larger picture. Here are seven conifer winged seeds, all collected in the Bull Bun district, Nevada, from the upper Eocene Chicken Creek Formation. For reference, the winged seed in the center is 10 millimeters in actual length. At lower right is an unspecified fir winged seed; at the upper left is a winged seed from an unspecified variety of pine. The remainder of the specimens belong to a species of spruce called scientifically Picea coloradensis, a fossil variety that shows affinities to both the modern Colorado Blue spruce and the Engelmann spruce. |

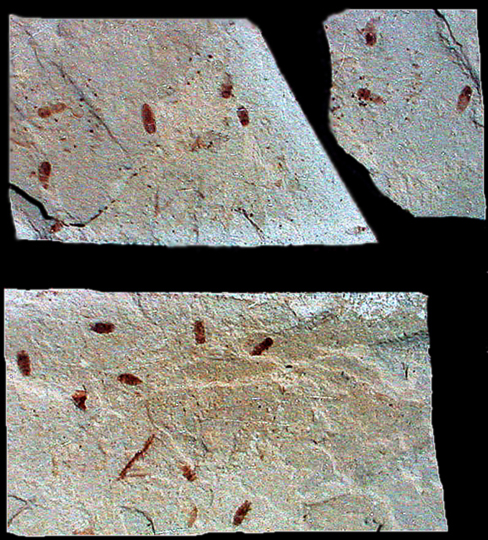

| Click on the image for a larger picture. Three insect fossils from the upper Eocene Chicken Creek Formation, collected from Bull Run Basin, Nevada; they appear to represent a variety of fly larvae perhaps similar to types sometimes noted in the world-famous Eocene Green River Formation of Colorado, eastern Utah, and Wyoming. The specimens are 8 millimeters long in actual dimension. |

| Click on the image for a larger picturel. Three small slabs of shale from the upper Eocene Chicken Creek Formation, Bull Run Basin, Nevada, bearing several dark-brownish, carbonized fossil fly larvae; none of the arthropods is longer than about eight millimeters.. |

|