| Introduction | Text: The Field Trip | Images: On-Site |

| Images: Fossils | Links: My Web Pages | Email Address |

|

Perhaps it is difficult to picture, but some 450,000 to 18,000 years ago a great fresh water lake covered roughly 83 square miles (236 square kilometers) of the present-day Mojave Desert in southern California. This was ancient Lake Manix, some 200 feet deep at its highest stand, created by a combination of flood waters from the ancestral Mojave River and an increase in precipitation during an interglacial period of the Pleistocene Epoch. Around the lake lived a fascinating variety of now extinct animals, including Dire wolves, mammoths, La Brea storks, Oregon gulls, Shasta ground sloths, and scimitar cats. Today, the remains of 21 species of mammals and 25 species of birds can be found in the sediments deposited in that relatively long-lived body of water--in addition to abundant ostracods (a minute bivalve crustacean), freshwater mollusks, and skeletal elements from a fish--the extant Tui Mojave Chub. Geologists have named those Late Pleistocene silts, sands and clays exposed in this part of San Bernardino County the Manix Formation, an Ice Age remnant which now yields an important diversity of nicely preserved vertebrate and invertebrate specimens that provide an invaluable paleontological chapter in the historical geology of the Mojave Desert district. The fossil mammal bones from the Pleistocene exposures were discovered sometime in the early 1900s by John T. Reed of San Bernardino, California. Reed was an amateur fossil prospector who immediately understood the significance of his find. He showed the bones to a geology student from the University of California, Berkeley--H.S. Mourning--who in turn took the information to the noted paleontologist/geologist John P. Buwalda. On January 22, 1914, Buwalda published a brief notice of the discovery of vertebrate fossils in the "Manix Beds" (his original name for the rock formation containing the fossils--a name derived from the Manix railroad siding situated near the most fossiliferous exposures of Pleistocene sediments) in the University of California Publications Bulletin of the Department of Geology, volume 7, number 24. This was a true pioneering work, as Buwalda observed in his report that "no reference to Pleistocene lake beds in this region has been found in the literature." Based on six species of mammals described from the lacustrine deposit, Buwalda dated the "Manix Beds" as Pleistocene, although he was unable to establish the exact stage of the epoch from which his vertebrate specimens were recovered. It is interesting to note, though, that professor Buwalda, in this initial reconnaissance investigation of the Pleistocene beds, correctly determined that the primary reason Lake Manix eventually disappeared was due to a downcutting of its outlet in the Afton Canyon region 40 miles east of Barstow. The rush of water through this "breach in the beach" some 18,100 years ago actually created Afton Canyon, a popular scenic attraction on the Mojave Desert today. In the years following Buwalda's original research, many Earth scientists have studied the fossil-bearing Late Pleistocene sediments that accumulated in Lake Manix. In 1934, Lawrence V. Compton wrote Fossil Bird Remains From The Manix Lake Deposits Of California, an article published in the avian scientific journal Condor, volume 36; perhaps unduly influenced by the presence of some small horse specimens in the fossil fauna, Compton originally thought that the Manix beds might be as old as Late Pliocene, but eventually concluded that they were more likely early Pleistocene in geologic age--a rough estimate later contradicted by more reliable avian and mammalian fossil material from the Manix Formation; today, the Manix beds are universally regarded as Late Pleistocene in age. The third important paper on the subject was Pleistocene Lake of the Afton Basin, California, by E. Blackwelder and E.W. Ellsworth, 1936, American Journal of Science 5th Series, volume 31. Blackwelder and Ellsworth recognized two separate periods of lacustrine deposition. The older of the two lakes disappeared they concluded due to desiccation, while the younger body of water vanished--as Buwalda had claimed many years before--when the overflow channel at Afton Canyon was eventually downcut enough to allow the ancestral Mojave River to flow freely across the land, draining the lake. More research followed. In 1954, H.H. Winters wrote an important scientific report that concentrated specifically on the fossils of the Manix Formation: The Pleistocene fauna of the Manix beds in the Mojave Desert, California, an unpublished masters thesis for the California Institute of Technology. During his field work Winters collected 12 species of fossil birds which were later (1955) described in detail by Hildegarde Howard in United States Geological Survey Professional Paper 264-J, Fossil Birds From Manix Lake California. In 1968, George T. Jefferson completed an unpublished masters thesis from the University of California, Riverside, The Camp Cady local fauna from Pleistocene Lake Manix. For several years Mr. Jefferson was associated with the George C. Page Museum, La Brea Discoveries, located at the world famous La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles, California--a site which contains the greatest accumulation of Late Pleistocene mammals and birds yet discovered on our planet. He has written exhaustively of the fossil fauna of Pleistocene Lake Manix, and in fact formally named and described the Manix Formation in his 1985 paper, Stratigraphy and Geologic History of the Pleistocene Manix Formation, Central Mojave Desert, California, Contributions to Science, number 352, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Jefferson also co-authored the 1982 report, Manix Lake and the Manix Fault Field Trip Guide, Quarterly San Bernardino County Museum Association volume 29, with Jeffrey R. Keaton and P. Hamilton. In the 1990s, Dr. Norman Meek contributed additional noteworthy scientific investigations of the Manix Basin. See his following references, for example: Geomorphic and hydrologic implications of the rapid incision of Afton Canyon, Mojave Desert, California, Geology Magazine, volume 17; unpublished doctoral dissertation for the University of California at Los Angeles, Late Quaternary geochronology and geomorphology of the Manix basin, San Bernardino County, California, 1990; and New discoveries about the Late Wisconsinan history of the Mojave River, San Bernardino County Museum Association Quarterly, 46(3), p. 113-117, 1999. The Upper Pleistocene Manix Formation is one of the most famous and paleontologically important fossil-yielding areas in all of the western United States. For this reason, the fossiliferous badlands carved in the Manix Formation were first set aside by the Bureau of Land Management as an Area of Critical Environmental Concern; numerous years later, the area became part of the federally protected Mojave Trails National Monument. This means that it is illegal to remove any fossil from the Manix Formation--vertebrate or invertebrate, for that matter--without a special permit issued by the administrative authorities. But all interested persons are certainly welcome to visit the region, a classic desert land of harsh extremes and austere beauty. Any particularly well preserved bones or invertebrate remains should be brought to the attention of a professional paleontologist, who will be able to asses their scientific value: this is a paleontologically priceless region. Each fossil specimen secured from the Manix exposures could help write yet another page in the historical geology of the Mojave Desert. It is imperative that professional paleontologists have the opportunity to examine the finds made by those who visit the area; and who knows, you might even have found a species that is new to science. Probably the best place to examine the Upper Pleistocene Manix Formation is Bassett Point, which includes the area most-studied by paleontologists. Here, the gray to pale-greenish and brownish clays, silts and sands of the Manix Formation are well-exposed along the course of the Mojave River, a bed of parched sand most of the time, devoid of all moisture. Two-hundred thousand years ago, however, that very spot would have been completely submerged beneath the pristine waters of an Ice Age lake. At Bassett Point one stands atop the youngest sediments of the Late Pleistocene strata. Approximately 100 yards (90m) west, in deposits slightly higher in the section, a bed of fresh water mollusks has been dated by the Carbon 14 radiometric age method at 19.1 thousand years old. A fossil horse bone from near the base of the 127 foot-thick (38m) Manix section yielded a radiometric age of roughly 350,000 years (a date not established with the Carbon 14 method, of course, which is accurate only up to around 50 thousand years); this is certainly the oldest vertebrate fossil horizon in the Manix Formation. Most of the fossil bones, though, have been collected from a narrow three-foot zone in the middle of the formation, vertebrate specimens dated by the Uranium-Thorium equilibrium method at 290 thousand years old. Two additional bone-bearing horizons occur in the Manix Formation, although they yield far fewer specimens than the older zone. One occurs a few feet above the main bone bed and has been dated by the Uranium-Thorium technique at 195 thousand years; the second is found throughout the uppermost 20 feet (6m) of the Manix Formation in strata approximately 60 to 19 thousand years old. Two widespread beds of fresh water mollusks also occur throughout the Manix Formation. The older of them yielded a Carbon 14 dating of 49 thousand years, while the younger shell horizon, also dated by the famous Carbon 14 radiometric age method, was determined to be 19.1 thousand years ago. The Manix Formation of San Bernardino County, California, has yielded one of the most significant fossil faunas of Late Pleistocene mammals and birds on the West Coast. Many of the species identified have also been recognized in the incredible tar traps of the famous Brea pits in Los Angeles and McKittrick. In addition to the mammals and birds, several other varieties of animal life have also been recovered from the sediments of Ice Age Lake Manix. These include five species of ostracods (a minute bivalve crustacean), two species of fresh water pelecypods, nine species of fresh water gastropods, two species of fish (the Tui Mojave Chub and Three-spine stickleback), and one species of reptile (the Western pond turtle). Among the 25 varieties of fossil birds identified from the Late Pleistocene section are such extinct forms as the Large-footed Cormorant, the Brea Stork, the Small Flamingo, Cope's Flamingo, Shufeldt's American Coot, and the Oregon Gull; living members of the avian fauna include the Arctic Loon, Eared Grebe, Western Grebe, American White Pelican, Double-crested Cormorant, Tundra Swan, Honker, Green-winged Teal, Mallard, Greater Scaup, Common Merganser, Ruddy Duck, Bald Eagle, Crane, sandpiper, a phalarope, a large gull, Golden Eagle, and the Great Horned Owl. In analyzing the variety of bird fossils in the Manix Formation, it is germane to note that 96 percent of the specimens are considered waterfowl. Also, two-thirds of the living members of the fauna presently prefer to feed exclusively on small fish. From this line of evidence, it appears probable that the Tui Chub represented in the fossil record here provided a substantial diet for many of the birds at Lake Manix. The life habits of living members of the fossil bird assemblage show that the primary Late Pleistocene habitats included open water, sandy beaches and abundant reedy marshlands. Many extant representatives of the fossil bird fauna range at present throughout southern California and can be found seasonally on the Salton Sea and other inland bodies of water; several living species prefer coastal marine conditions or inland areas in the San Joaquin Valley of California. Among the 21 species of mammals identified from the Manix Formation, the following extinct types can be recognized: a medium-sized ground sloth; the Shasta Ground Sloth; a large ground sloth; a mammoth; the Dire Wolf; a short-faced bear; a scimitar cat; the Western Camel; the Minidoka Camel; a Large-headed llama; an Antique (Ancient) Bison; the small Mexican Horse; and a large Western Horse. Living members of the mammalian fauna include a jack rabbit, a mouse, Coyote, a bear, Puma, Pronghorn, and a Bighorn Sheep. Plant remains in the Late Pleistocene beds are rare, but a few poorly preserved specimens have been encountered, mainly carbonized wood and leaf fragments that have not appreciably helped to determine the kind of vegetation that once existed here. Better evidence is supplied by fossil pollen found at the Calico Early Man archaeological excavation site near Yermo, California, about 15 miles west of Bassett Point, in alluvial material that correlates with strata in the Manix Formation some 100 to 75 thousand years old. Here scientist S. Peterson recovered pollen specimens from pine, oak, sagebrush, ragweed (woe to American aboriginal allergy sufferers!), goosefoot and juniper. Such plants were probably widely distributed in the moderate uplands bordering Lake Manix. In an attempt to better understand the Ice Age vegetation of Lake Manix time, scientists have also analyzed the plant remains in packrat middens that date from the Late Pleistocene. Based on the fossil gatherings of such rodents in southern Nevada, Arizona and southeastern California, there is convincing evidence to suggest that modernday woodlands now restricted by altitude were some 3,000 feet (910m) lower during deposition of the Manix Formation. This means that Pinyon pine and juniper, presently kept to a regional minimum elevation of 5,850 feet 1,780m), were in all likelihood thriving at 2,600 feet (790m) 200 thousand years ago in the neighboring Alvord, Cady, Calico and Newberry Mountains. Today these mountains are practically barren of any kind of vegetation. From the available evidence, it appears that juniper, sagebrush and creosote brush covered the alluvial slopes surrounding Lake Manix. Slightly higher elevations supported a Pinyon pine-juniper-evergreen live oak woodland, while white fir likely formed a dense forest in the Newberry and Ord Mountains at an altitude of 3,950 feet (1,200m); present-day conditions keep white fir a a minimum elevation of 7,150 feet (2,180m). Bordering the lake were marshlands that probably supported reeds, rushes, pondweed, duckweed and cattails. Patches of grasslands apparently existed in the drier flats, much like they do in present-day regions characterized by a similar juniper-oak woodland. Today, the luxuriant growth of Pleistocene plants has vanished. In their place is an extensive barren badlands of pastel sediments which yield a wealth of fossils. The most commonly encountered mammalian remains belong to the Western Camel (an impressive reconstruction of this creature can be viewed at the George C. Page Museum of La Brea Discoveries in Los Angeles), the Large-headed llama, the large Western horse, the Mexican Horse and the mammoth. Among the birds--whose hollow, delicate bones are miraculously well preserved in the Manix Formation-- the most frequently reported species include the Western Grebe, the Small Flamingo, The American White Pelican, and the Honker. Specimens of the Tui Chub and Three-spine stickleback, while found scattered throughout the fine silts and sands of the upper half of the Manix Formation, are often concentrated in the middle of the sedimentary section in strata roughly 290 thousand years old. Curiously, the bones and scales from these species of fish are the most commonly encountered vertebrate fossils in the Late Pleistocene beds. The remains are often rather small, however, and even professional paleontologists get down on all fours, with nose to the ground, when prospecting a likely fish-bearing horizon in the Manix exposures. Also living in ancient Lake Manix were numerous gastropods and pelecypods. Such mollusks are among the most abundant of forms found in the Late Pleistocene section. The two widespread beds crammed with well preserved snails and clams occur near the top of the formation in distinct zones about 18 feet (5m) apart. Their original shell material has been preserved intact, although it is extremely brittle. Both mollusk-bearing beds yield a bewildering mixture of forms that, individually, prefer different fresh water habitats--such as rivers, streams, ponds, lakes, bogs and swamps. Apparently this unusual assemblage of snails and clams resulted from deposition due to flooding. Mollusks from every local habitat were jumbled together by the rising waters of Ice Age storms, then they were transported and dumped into the reaches of Lake Manix by the engorged streams. Those streams also brought in loads of clays, silts and sands over a period of perhaps 430 thousand years--sediments that contributed to the 127 foot-thick (38m) section presently exposed on the Mojave Desert. Today, it is indeed fascinating and fun to hike amidst the badlands carved in those lake-deposited, loosely consolidated materials of the Upper Pleistocene Manix Formation. The exposed strata have been preserved in an essentially horizontal bedding attitude, and there is a gradual and easily negotiated slope that leads downward from Bassett Point to the outcrops below. With each step taken, you move back thousands of years in geologic time to a lush late Pleistocene landscape of water and green and abundant animal life. When you visit the 450 to 18 thousand-year-old Manix Formation, take some special time to enjoy the view afforded at Bassett Point. Below is stark desert, a blistered region of subdued hues, a harsh and unforgiving landscape where vegetation is scarce and visible animal life apparently nonexistent. That a great Ice Age lake once covered this land seems improbable, but the fossils in the sediments prove the case--that 290 thousand years ago you would have seen flamingos, pelicans, ducks, eared grebes, gulls, storks, cranes and loons swimming and wading in Pleistocene Lake Manix, a vast 83 square miles (236 square km) of pristine, clear glacier-fed waters that teemed with fish for the hungry birds. Above the lake would circle Bald Eagles and Golden Eagles and Great Horned Owls--large predatory birds, raptors, ready to seize the unwary in their powerful talons. Amid the surrounding countryside a Shasta Ground Sloth might be seen leisurely browsing on the upper branches of a juniper tree; a pack of hungry Dire Wolves is cutting off a large Western Horse from the herd; and a scimitar cat has just brought down a baby mammoth on a open grassy plain. There is blood gushing from the punctured jugular and the vulturous condors soar high above. In the distance, a violent storm is developing, a storm that will create a rushing flood of waters destined to sweep along the carcasses of both mammals and birds to the momentarily placid lake; there, the bones will be covered by fine clays, silts and sands, to remain hidden for some 290 thousand years until they are seen for the first time by human eyes in the middle of a great desert. |

| A seeker of Ice Age times on the Mojave Desert stands amidst the Upper Pleistocene Manix Formation. Here, the view is looking slightly north of eastward, just downslope from Bassett point, to the eroded uppermost sediments of Late Pleistocene Lake Manix. The gully which runs just behind the individual was loaded with abundant, perfectly preserved skeletal elements from the Tui Mojave Chub, indicating widespread lacustrine (lake) conditions in this part of the present-day Mojave Desert some 19,000 years ago. |

| The view is roughly eastward from the vicinity of Bassett Point. Common to abundant Tui Mojave Chub skeletal elements weather out of the lake-deposited sands and silts of the Upper Pleistocene Manix Formation within the foreground and middleground of this panorama--in addition to occasional bones from mammals and birds. Shell beds loaded with nicely preserved fresh water gastropods and pelecypods occur just out of sight at right side of photograph. |

| Six fossil fish vertebrae from a Tui Mojave Chub (Gila bicolor mohavensis)--the scale is in millimeters--Upper Pleistocene Manix Formation, San Bernardino County, California. They came from the uppermost few meters of the Manix Formation, so they're likely some 40-to-19 thousand years old; collected long before the Manix Lake Beds were first set aside as an Area Of Critical Environmental Concern and then later included in Mojave Trails National Monument. |

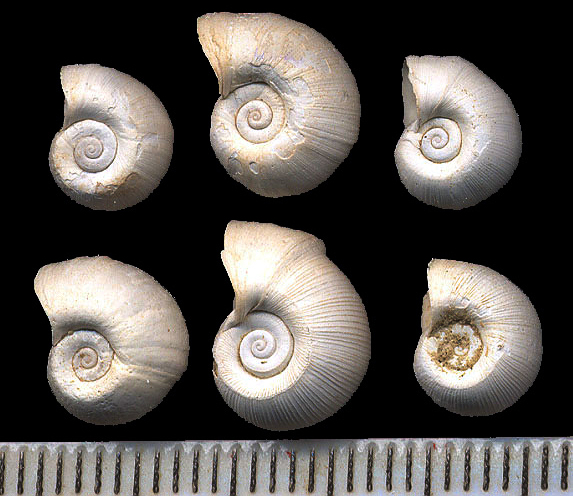

| Here are six fossil fresh water gastropods from the youngest phases of deposition of the Upper Pleistocene Manix Formation, San Bernardino County, California--they are roughly 19 thousand years old, and all belong to the genus Planorbella. The scale is in millimeters. Specimens were collected long before the Manix Lake Beds were first aside as an Area Of Critical Environmental Concern and then later included in Mojave Trails National Monument. |

| A camel metapodial (one of the foot bones) in the Upper Pleistocene Manix Formation San Bernardino County, California. Called scientifically, Camelops hesternus; for scale, the geology hammer is 33 centimeters long (almost 13 inches). The vertebrate fossil is lying in the youngest phases of Lake Manix Basin sedimentary deposition, so it's between 40 and 19 thousand years old. |

|