|

Many fossil prospectors across America are familiar with

the name Sharktooth Hill. This is an old and venerable locality,

where innumerable shark teeth and marine mammal bones have been

collected over the years. It is certainly one of the most famous

vertebrate fossil sites in the world--a place where roughly 125

species of sharks, bony fishes, sea mammals, sea turtles, marine

crocodiles, birds and even land mammals have been found.

The fossils are concentrated in a rather narrow one-to

four-foot thick layer in the Round Mountain Silt Member of the

Middle Miocene Temblor Formation, which is exposed over several

square miles in the erosion-dissected western foothills of California's

southern Sierra Nevada. Although the diggings at Sharktooth Hill

have historically yielded the most prolific occurrences of the

16 to 15 million-year-old vertebrate material in the Round Mountain

Silt, the so-called Sharktooth Hill bone bed continues to provide

collectors with nicely preserved fossils wherever it outcrops.

This is indeed fortunate for amateur paleontology students,

since Sharktooth Hill presently lies on private property and

is in fact a registered national landmark; unauthorized collecting

is obviously forbidden at that most famous of sites, but several

other fossil-bearing zones in the immediate vicinity can still

be explored by interested amateurs--at least by direct permission

from the many local landowners, who presently own almost all

of the Sharktooth Hill bone bed exposures not included in the

Sharktooth Hill paleontological preserve.

And there is certainly no doubt about it--lots of folks

over lots of historical time have visited the Sharktooth Hill

area to investigate its Middle Miocene marine vertebrate paleontological

preeminence.

The history of fossil collecting at Sharktooth Hill goes

all the way back to the middle portion of the 19th Century. In

August of 1853 geologist William P. Blake reported the occurrence

of well-preserved shark teeth and sea mammal bones from the general

area of present-day Sharktooth Hill. At the time, Blake, employed

by the United States Topographical Corps, was conducting a field

survey for possible railroad routes from the Eastern Seaboard

to the West Coast. His discovery is generally heralded as the

first confirmed report of fossil shark teeth west of the Rocky

Mountains. Blake's important collection was eventually studied

in 1856 by the legendary Swiss geologist and paleontologist Louis

Agassiz, who at the time was one of the leading authorities on

vertebrate fossils.

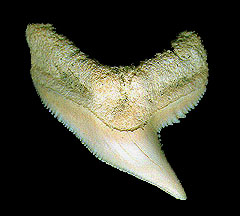

Sometime after Blake's discovery, enthusiastic amateurs

began to explore the Middle Miocene deposits in the dusty hills

northeast of present-day Bakersfield. Nobody knows for sure who

first coined the name "Sharktooth Hill" to describe

the rich fossil occurrences, but there is little doubt that the

term accurately identifies the most popular type of fossil found

there. Even today, in the centuries after the original find by

geologist Blake, well-preserved shark teeth continue to attract

considerable attention.

As the population of the southern San Joaquin Valley and

of metropolitan Los Angeles (only 90 miles south of Bakersfield)

began to increase during the latter half of the 1800s, so did

the numbers of regular visitors to Sharktooth Hill. From the

beginning of its popularity, the site became a mecca of sorts

for fossil hunters. Shark teeth and sea mammal remains in the

middle of an arid valley, over 100 miles from the Pacific Ocean,

became irresistible attractions and have drawn innumerable individuals

to this site over the decades.

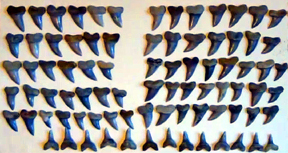

Perhaps the most famous amateur collector to visit Sharktooth

Hill was Charles Morrice, a clerk for the Pacific Oil Company.

Morrice became ardently interested in collecting fossil specimens

from the bone bed in 1909 during his off-work hours. Over the

course of several years he personally excavated hundreds of thousands

of shark teeth weighing, literally, several tons. There is a

historically valuable photograph of the legendary Morrice in

the informative reference volume, History of Research at Sharktooth

Hill, by Edward Mitchell (published by the Kern County Historical

Society in 1965); Morrice is shown on-site at Sharktooth Hill,

by one of his many digs, with a huge bucket filled to the brim

with nicely preserved shark teeth of all kinds. At first, Morrice

would simply give his finds away to friends, relatives and acquaintances.

But he eventually became an indefatigable, scientifically motivated

collector, donating his exhaustive collections to museums and

universities throughout the world. In recognition of his contributions

to science, two extinct animals from the Sharktooth Hill bone

bed have been named in honor of Charles Morrice: a shark, Carcharias

morricei, and a sperm whale, Aulephyseter morricei.

In later years, the two most important amateur collectors in

the Sharktooth Hill bone bed were Bob Ernst (who before his passing

collected upwards of 2 million vertebrate remains) and Russ Shoemaker,

private land owners in the Sharktooth Hill district who donated

exhaustive amounts of Middle Miocene vertebrate fossil material

to any number of museums and scientific institutions throughout

the world.

Although the prolific bone bed at Sharktooth Hill had been

known to paleontologists since the 1850s, the first formal scientific

investigation of the fossil-bearing layer was not conducted until

1924. That year the California Academy of Sciences initially

decided to spend four months in the field analyzing the fossil

deposit on-site. But the diggings proved so productive and challenging

that the Academy continued to collect there, off and on, through

the 1930s. After the preliminary fieldwork was completed, paleontologists

required several years to clean, catalog and identify the abundant

material recovered. In all, some 18 new species of mammals, birds,

sharks, rays and skates were named from the collections amassed.

From 1960 to 1963 a second major scientific study of the

Sharktooth Hill bone bed was undertaken, this time by the Natural

History Museum of Los Angeles County. To expose an undisturbed

layer of the fossil-rich zone, researchers bulldozed away roughly

15 feet of the barren silty overburden. Using whisk brooms and

awls, the scientific teams then carefully removed the essentially

in-place bones and teeth from the 16 to 15-million-year-old sediments.

This was the first time that paleontologists had actually been

able to observe firsthand the relationships of the fossils as

they lay preserved in the bone bed. Thus, not only were innumerable

perfectly preserved bones and teeth recovered, but invaluable

information was also gathered on how the remains of the preserved

animals came to rest on the silty floor of a Miocene sea. A major

highlight of the museum excavations was the discovery of an almost

fully intact skeleton of the extinct sea lion, Allodesmus.

Since articulated remains of marine mammals are uncommon in the

primary bone-bearing zone, such a complete specimen ranks as

one of the most significant finds in the history of explorations

at Sharktooth Hill. Another mostly complete, articulated Allodesmus

was discovered in deposits above the bone bed many years

later by the dedicated amateur fossil hunter Bob Ernst, who donated

the remains to science--a fine sea lion specimen now housed at

the Buena Vista Museum in Bakersfield.

Perhaps the zenith of paleontological investigations at

Sharktooth Hill happened during the 1960s and 1970s. Research

crews from universities and museums throughout the United States

visited the area, carting away tons of excellently preserved

fossil material. Amateur interest in the bone bed also increased,

and many a Southern Californian was likely first introduced to

the rewards of fossil hunting at Sharktooth Hill.

But the steady stream of visitors appeared to be getting

out of hand. Much of the precious bone-bearing horizon was rapidly

disappearing. Scientists expressed justifiable concerns that,

if left unprotected, the most fossiliferous sections of the bone-yielding

horizon would soon be obliterated. The proper government officials

agreed with this assessment and in May, 1976, Sharktooth Hill

was added to the United States Landmark Registry, a designation

which protects the locality from unauthorized collectors.

The Sharktooth Hill bone bed has provided paleontologists

with the single largest assemblage of Middle Miocene marine vertebrate

animal fossils in the world (the famous Miocene Calvert Formation

of Maryland also produces many kinds of marine vertebrate remains).

The impressive list of marine mammal specimens alone from the

Temblor Formation includes dolphins and dolphin-like creatures,

porpoises, sea lions, whales, sea cows, walruses, seals and an

extinct hippopotamus-like fellow called Desmostylus--a

10-foot-long animal related to the elephant that evidently walked

around on the sea floor crushing shellfish with its massive,

powerful jaws. Also identified have been extinct large turtles,

a marine crocodile, many kinds of bony fishes, and some 20 species

of birds--in addition to the astoundingly abundant sharks and

rays.

In addition to the marine fauna, several skeletal elements

from land mammals have also been taken from the fossil beds.

These include a lower jaw of the mustelid (weasel-like) Sthenictis

lacota; a lower jaw of the huge amphicyonid, or "beardog"

Pliocyon medius; the dog Tomarctus optatus; the

three-toed horses "Merychippus" brevidontus

and Anchitherium sp.; the rhinoceroses Aphelops megalodus

and Teleoceras medicornutum; the tapir Miotapirus sp.;

the deer-like dromomercyids Bouromeryx submilleri and

Bouromeryx americanus; the protoceratid (sort of a cross

between a modern deer and a cow) Prosynthetoceras sp.;

and the gomphothere (an extinct proboscidean) Miomastodon

sp. Such remains are exceedingly rare, though, and are usually

considered anomalies in the local Middle Miocene fossil record.

Their presence in proved marine-deposited rocks points to preservation

in shallow sea waters, since it is unlikely that the carcasses

of land animals could have been transported far from the ancient

shoreline before they settled to the ocean floor.

All of these remains lie waiting to be uncovered in the

rolling brush-covered western foothills of the southern Sierra

Nevada, several miles northeast of Bakersfield in Kern County,

California.

One of the better extensions of the fabulous bone bed was

for decades a genuinely fun and educational place to visit. Here,

shark teeth and various fragmental skeletal elements from a variety

of marine mammals constituted the available fossilized assemblage,

a place that for many years amateur collectors were welcome to

visit; on any given day of the week, for example, one could expect

to find at least a handful of folks (on weekends, the numbers

of visitors increased exponentially) exploring the prolific Middle

Miocene fossil horizon, collecting loads of well preserved shark

teeth and generally enjoying their outdoor experience without

having to worry about legal restrictions on their fossil-hunting

activities. The local law enforcement and BLM authorities left

the collectors alone, as long as the area remained free from

litter and vandalism, of course. When I last visited the locality,

enthusiastic visitors were still allowed to gather Middle Miocene

shark teeth and miscellaneous sea mammal bones, but there is

no guarantee that the area has remained accessible to unauthorized

amateurs. If the site has been formally closed off, make certain

that you obey all the rules and regulations: do not attempt to

climb over a locked gate, or with reckless disregard disobey

No Trespassing signs which may have sprung up to warn visitors

that their presence is no longer welcome.

Upon stepping out of one's vehicle to survey the territory,

where to search for the fossilized specimens was quite obvious

to all visitors. Along the steep to moderately inclined slopes

above the parking area one could observe the unmistakable World

War I-style infantry entrenchments that, dipping at a low angle

of approximately four to six degrees to the southwest, marked

the trend of the prospected bone bed. These excavations were

made by armies of a different sort: fossil hunters who in their

determination to recover shark teeth and marine mammal bones

had created a single extended trench along the entire length

of the exposed fossiliferous horizon in this immediate area.

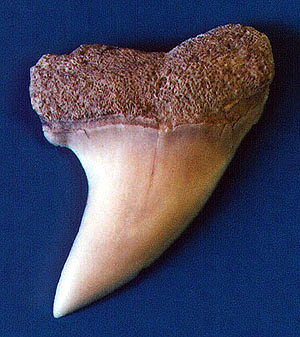

The shark tooth-bearing layer averaged roughly one foot

thick here, but was often difficult to spot due to the random

digging of previous fossil prospectors. It helped to watch for

the dark-brown fragmental bones of sea mammals embedded in the

pale-gray matrix of the Round Mountain Silt; these were the most

common finds in the Sharktooth Hill bone bed exposures, although

the perfectly preserved shark teeth remained the prized items

sought by the majority of visitors. The best way to locate fossils

was to settle into your "battlefield" entrenchment

and commence digging. Here, there was just no substitute for

good old-fashioned manual labor. Most collectors simply dug into

the fossil-bearing zone with a pick or shovel, carefully inspecting

each chunk of Middle Miocene material removed from the exposure.

Others brought along some kind of screening device--even a riddle

(usually employed by gold seekers)--into which they dumped fossil-bearing

dirt. After the sands and silts had passed through the fine mesh,

any bones and teeth scooped up remained atop the screen, ready

to be packed away for safekeeping.

Unfortunately, the fossil zone was not as prolific as at

classic Sharktooth Hill, where almost any section of the bone-yielding

horizon explored managed to yield abundant perfectly preserved

material. Weathered-free fossils were sometimes found, too, especially

after a heavy rainy season, before the hordes of eager collectors

had descended on the hill for a new season of fossil-finding;

at the once-accessible locality, though, freely eroded forms

were conspicuously absent. This was best explained by the great

numbers of collectors who visited the site each year. Any remains

that had naturally washed out of the 16 to 15-million year-old

sediments were in all likelihood immediately plucked up and stored

away by the lucky few who happened upon them. As this specific

locality remained for many years the primary spot where amateurs

were still legally allowed to collect fossils from the Sharktooth

Hill bone bed, it was not surprising that such easy pickings

were nonexistent.

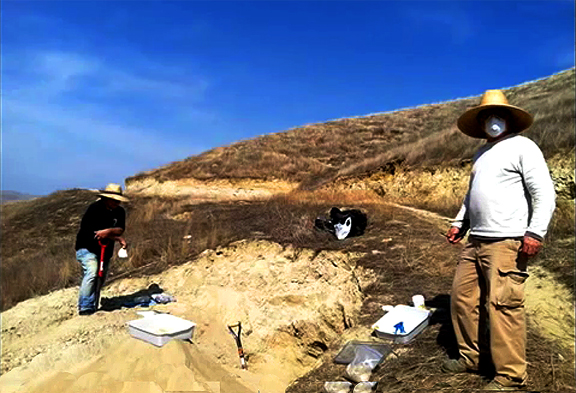

Other than keeping well-hydrated during hot summer days,

the major hazard one faced at the fossil locality, and indeed

wherever one happened to dig into the Sharktooth Hill bone bed,

was exposure to Valley Fever. This is a potentially serious illness

called scientifically, Coccidioidomycosis--or "coccy"

for short; it's caused by the inhalation of an infectious airborne

fungus whose spores lie dormant in the uncultivated alkaline

soils of California's southern San Joaquin Valley: And the region

in which the Sharktooth Hill bone bed occurs is known to contain,

in places, significant concentrations of the spores which cause

this disease. When an unsuspecting and susceptible individual

breaths the spores into his or her lungs, the fungus springs

to life, as it prefers the moist, dark recesses of the human

lungs (cats, dogs, rodents and even snakes, among other vertebrates,

are also susceptible to "coccy") to multiply and be

happy. Most cases of active Valley Fever resemble a minor touch

of the flu, though the majority of those exposed show absolutely

no symptoms of any kind of illness; it is important to note,

of course, that in rather rare instances Valley Fever can progress

to a severe and serious infection, causing high fever, chills,

unending fatigue, rapid weight loss, inflammation of the joints,

meningitis, pneumonia and even death. Every fossil prospector

who chooses to visit the Sharktooth Hill bone bed--and the southern

San Joaquin Valley, in general--must be fully aware of the risks

involved.

With regard to the direct risk of contracting Valley Fever

while digging in areas where the Sharktooth Hill bone bed occurs,

a year 2012 posting at the Facebook page of a major commercial,

fee fossil dig operation situated on private property sheds at

least a modicum of light on the subject:

"Question: How many people catch Valley Fever after

digging at your quarries?

"Honestly, more participants have had encounters with

rattlesnakes, than have contracted Valley Fever (VF). Nearly

all of our participants DO NOT use dust masks while digging.

We have had over 2000 diggers on the quarry in the last 18 months,

and we only have 3 reported instances of participants contracting

VF. That falls well belo...w the Kern County average, and may

say something as to the prevalence of the spores in areas we

are excavating. We have four quarries open currently, all located

below the surface, in fossil beds aged between 14 and 18 million

years. This 'soil time-line' predates the emergence of c. immitis

by over 10 million years."

So, here's the bottom line, the proverbial upshot--Valley

Fever spores definitely exist in California's southern San Joaquin

Valley, and Valley Fever can indeed be contracted from digging

in the area where the Sharktooth Hill bone bed occurs. The statistic

that "only" three individuals in 18 months of supervised

digging there have reported contracting Valley Fever may or may

not assuage the justifiable concerns of potential visitors.

The Round Mountain Silt Member of the Tumbler Formation,

which contains the Sharktooth Hill bone bed (and could harbor

fungal spores of Valley Fever--a noncollectible item if there

ever was one), apparently accumulated roughly 16 to 15 million

years ago in a semi-tropical embayment. This great body of water

covered all of the present-day San Joaquin Valley from the Salinas

area southward to the Grapevine Grade, just north of Los Angeles.

The incredible bone bed was evidently preserved along the southeastern

edges of the sea in waters no deeper than about 200 feet--an

estimate based on the presence of fossil rays and skates, whose

modern-day relatives prefer such relatively shallow depths. It

is illuminating to note that all of the living members of the

fossil fauna recovered from the bone layer can be found today

in Todos Santos Bay off Ensenada, Baja California Norte; the

extant marine mammals of the Sharktooth Hill fauna all migrate

there during the winter months.

While scientists understand very well the variety of animals

that formerly lived in the Middle Miocene Temblor-period sea,

they are less certain of what caused restricted preservation

in such a narrow bed in a locally unfossiliferous deposit. Although

the Temblor Formation does yield moderately common fossil mollusks

and echinoids elsewhere in its area of exposure (Reef Ridge in

the Coalinga district, for example), the Sharktooth Hill bone

bed occurs in sediments that are mysteriously barren of any other

kinds of organic remains. In an interval several hundred feet

both above and below the bone-bearing horizon there is absolutely

no trace of past animal or plant life.

Typically, such a shallow marine environment as is suggested

by the bone bed would be expected to include many sand dollars,

gastropods, pelecypods and a wide variety of microscopic plants

and animals such as diatoms and foraminifers. But such is not

the case here. Even after decades of assiduous, dedicated scientific

examination, vertebrate animal specimens remain the only diagnostic

types of fossil specimens yet recovered in abundance from the

Sharktooth Hill bone bed (a few internal casts of gastropod and

pelecypod shells have also been reported from the bone bed, in

addition to occasional coprolites, invertebrate burrows, and

gypsum-coated pieces of petrified wood--none of which is particularly

significant or diagnostic, except to say that such occurrences

support the idea that the bone bed formed in relatively shallow

waters).

Such an unusual abundance of diverse species of marine

mammals, sharks, birds, rays, skates and even land mammals requires

a unique mechanism of preservation. Clearly the curious mixing

of both land and marine vertebrates in the same layer points

to an as-yet incompletely understood set of circumstances. Needless

to report, ever since the bone bed's discovery on that summer

day way back in 1853, investigators have wondered just what events

could have created such a remarkable concentration of vertebrate

remains in a narrow horizon, to the exclusion of all other marine

invertebrates normally associated with a shallow-water environment.

Several ideas have been advanced to explain the rare occurrence.

One of the earliest explanations was offered during the

first quarter of the 20th Century by paleontologist Frank M.

Anderson of the California Academy of Sciences. Anderson suggested

that violent volcanism in the region poisoned the Miocene waters

with ash and noxious gasses, causing the sudden extinction of

the fauna. While it is true that widespread volcanic activity

occurred in the Middle Miocene of the present-day San Joaquin

Valley, there is no direct evidence to suggest that the Sharktooth

Hill fauna was adversely affected by it.

A second hypothesis states that during the Middle Miocene,

the bay in which the Sharktooth Hill animals lived became landlocked.

As the waters gradually evaporated the unlucky inhabitants were

doomed to try to survive in an increasingly smaller area, until

at last the creatures succumbed, thus creating a narrow zone

in which their skeletal and tooth remains were concentrated.

Yet another explanation concerns the "red tide"

phenomenon. Occasionally, a toxin-producing marine microbe multiplies

so rapidly that it kills smaller fish by the millions. The organism

contains a minute amount of a potent poison that can be easily

concentrated in the food chain. Larger fish consume the smaller

types that feed on the lethal organism until, eventually, all

of the fish are killed.

An additional once-popular proposal was that the Middle

Miocene Sharktooth Hill area was a great calving ground for marine

mammals, an irresistible attraction for sharks who seasonally

feasted on the animals gathered there to give birth. Unfortunately,

there is a paucity of juvenile sea mammal bones in the deposit--not

the amount one would reasonably expect to find preserved in the

Round Mountain Silt Member of the Temblor Formation had the area

witnessed for thousands upon thousands of seasons youngsters

cavorting in the same warm waters that held their predators--the

sharks.

Other possible mechanisms of deposition proposed for the

famed bone bed are turbidity currents--which are masses of water

and sediments that flow down the continental slope, often for

very long distances. Presumably, the carcasses of sea and land

animals were caught up in such underwater sediment flows, their

bones transported for considerable distances before the remains

dropped out of suspension in a submarine canyon, far removed

from the Middle Miocene shoreline. Perhaps favoring this explanation

is the fact that many of the vertebrate remains from the bone

bed reveal obvious signs of wear and tear, suggesting some degree

of transport and agitation prior to their eventual burial. As

a matter of fact, this is the one specific scenario of bone deposition

that most closely matches the evidence; indeed, it's the single

most widely accepted method by which literally millions of sea

mammal bones and shark and ray teeth could have possibly been

preserved in such a narrow interval, to the exclusion of virtually

every other kind of marine life.

This is but a sampling of the ideas proposed to account

for the Sharktooth Hill bone bed. Unfortunately (for the theorists

who suggested them), all but one of the above proposals--the

turbidity current idea, specifically--are quite simply put flat-out

wrong. They have been disproved, falsified. Over the years, there

have probably been as many hypotheses advanced as there are scientific

speculators to invent them. Suffice it to say that no one single

explanation, save the turbidity current proposal, has yet been

delivered to answer all the questions posed by this famous bone

bed of the Middle Miocene.

In early 2009, though, some researchers claimed that the

problem had been solved once and for all. The "definitive"

explanation--as published by The Geological Society Of America

in a paper entitled, "Origin of a widespread marine bonebed

deposited during the middle Miocene Climatic Optimum" by

Nicholas D. Pyenson, Randall B. Irmis, Jere H. Lipps, Lawrence

G. Barnes, Edward D. Mitchell, Jr., and Samuel A. McLeod--is

that the Sharktooth Hill Bone Bed accumulated slowly above a

local disconformity over a maximum of 700 thousand years due

to sediment starvation timed to a major transgressive-regressive

cycle during middle Miocene times 15.9 to 15.2 million years

ago. The upshot here, according to the authors, is that the world-famous

bone-bed is not the product of a mass dying, neither is it the

inevitable result of red-tide poisoning, nor the remains of animals

killed by volcanic eruptions, nor the preservations of vertebrates

through the concentrating action of turbidity currents--not even

the site of a long-term calving region where sea mammals birthed

and sharks hunted can fully explain the fabulous bonanza bone

layer. The Sharktooth Hill Bone Bed came about, the scientists

claim, over thousands of years due to slow, steady bone accumulation

during a period of geologic time when very little clastic sedimentation

(sands and silts and muds) occurred.

Perhaps this new research has indeed finally resolved the

mysteries surrounding the deposition of likely the greatest concentration

and diversity of fossil marine vertebrates in the world. The

turbidity current idea still holds water (pun intended) for many,

though, and will likely remain a lasting viable explanation for

many folks in the paleontological and geological communities.

Research on the Sharktooth Hill area has been exhaustive,

to say the least. Reference materials on the subject abound.

Probably the single best book to consult is the aforementioned

History of Research at Sharktooth Hill, Kern County, California,

by Edward Mitchell. Other worthwhile works include Birds from

the Miocene of Sharktooth Hill, California, in Condor,

Volume 63, number 5, 1961, by L.H. Miller; Sharktooth Hill,

by W.T. Rintoul, 1960, California Crossroads, volume 2, number

5; and the July 1985 issue of California Geology, published by

the California Division of Mines and Geology, in which an excellent

article appears entitled, Sharktooth Hill, Kern County, California,

by Don L. Dupras.

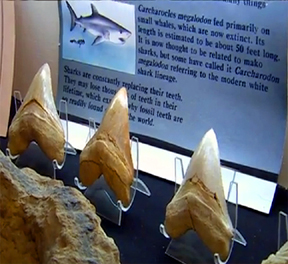

The once-accessible locality used to make a terrific substitute

for Sharktooth Hill. While the fossil remains were obviously

not as plentiful as at the more-famous site, amateur collectors

and professional paleontologists alike continued to find many

beautifully preserved shark teeth and marine mammal bones in

the fabulous Sharktooth Hill bone bed. It is a world-class paleontological

deposit which has yielded some 125 species of vertebrate animals

from the Middle Miocene of 16 to 15 million years ago--a time

when a tranquil semi-tropical sea similar to Todos Santos Bay

off Ensenada covered the present San Joaquin Valley. It was a

time when the ancestors of great white sharks lived where vast

fruit orchards now grow in the agriculture-rich Great Central

Valley of California.

|