|

Introduction

Visit the Coso Range Wilderness in Inyo County, California,

west of Death Valley National Park at the southern end of California's

Owens Valley, where vertebrate fossils some 4.8 to 3.0 million

years old can be observed in the Pliocene-age Coso Formation:

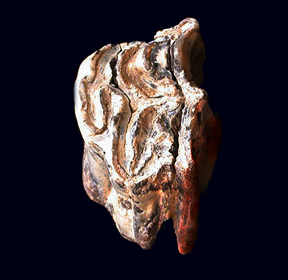

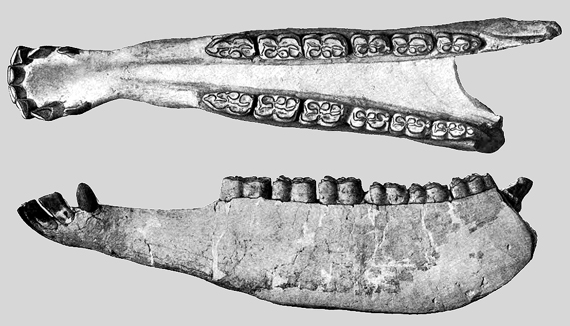

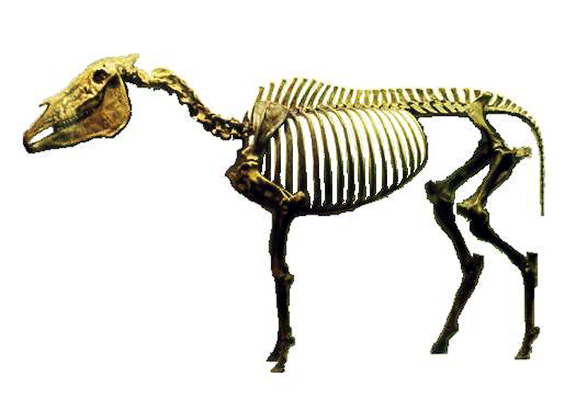

It's a paleontologically significant place that yields many species

of mammals, including the remains of Equus simplicidens, the

Hagerman Horse, named for its spectacular occurrences

at Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument in Idaho; Equus

simplicidens is considered one the earliest known members

of the genus Equus, which includes the modern horse

and all other equids.

Please note that fossil collecting is not allowed

within the designated Coso Range Wilderness, except by special

permit issued by the Bureau of Land Management--a permit given

only to individuals who matriculated from an accredited university

with a minimum B.S. degree, or represent a museum whose credentials

meet the necessary standards of excellence.

And now for the obligatory words of caution. Endemic

to the Mojave Desert of California, including the Las Vegas,

Nevada, region by the way, is Valley Fever. This is a potentially

serious illness called, scientifically, Coccidioidomycosis, or

"coccy" for short; it's caused by the inhalation of

an infectious airborne fungus whose spores lie dormant in the

uncultivated, harsh alkaline soils of the Mojave Desert. The

Coso Mountains lie near the northern known edges of Valley Fever

prevalence within the Mojave Desert province. When an unsuspecting

and susceptible individual breaths the spores into his or her

lungs, the fungus springs to life, as it prefers the moist, dark

recesses of the human lungs (cats, dogs, rodents and even snakes,

among other vertebrates, are also susceptible to "coccy")

to multiply and be happy. Most cases of active Valley Fever resemble

a minor touch of the flu, though the majority of those exposed

show absolutely no symptoms of any kind of illness; it is important

to note, of course, that in rather rare instances Valley Fever

can progress to a severe and serious infection, causing high

fever, chills, unending fatigue, rapid weight loss, inflammation

of the joints, meningitis, pneumonia and even death. Every fossil

enthusiast who chooses to visit the Mojave Desert must be fully

aware of the risks involved.

Field Trip

To The Coso Bone-Bearing Badlands

An inviting route to Death Valley National Park is State

Highway 190 out of Olancha in California's southern Owens Valley.

Not only is this a much-scenic and reliably accessible pathway

to one of the world's favorite haunts, but it also places visitors

within convenient striking distance of a most fascinating vertebrate

fossil locality in the federally established and administered

Coso Range Wilderness--an area no longer accessible to motor

vehicles, of course, though it's still wide open for inspection

by foot and other non-mechanized means.

Perhaps not a few folks remain unfamiliar with this particular

area, and I can surely see why. You just can't spot the bone-bearing

beds from the asphalt and, besides, it's more than probable that

many a traveler has their eyes fixed on the ever-looming and

impressive hulk of the Panamint Mountains up ahead--the range

which guards the western side of Death Valley, proper.

The Cosos are that at first blush nondescript piece of

territory off to the east and southeast as you speed along the

southern fringes of Owens Lake between Highway 395 and the intersection

with State 136 to Keeler. They are primarily of igneous origin,

born of fire and brimstone, the savage spewings of explosive

Cenozoic Era molten lavas in combination with Mesozoic Era batholithic

instrusive granites--as unlikely a source of fossil specimens

as one could be excused for believing. Yet, tucked way back in

the rugged Coso recesses lie the eroding badlands of an ancient

lake system which yields up many fossil bones.

The vertebrate remains that await discovery in the Coso

Mountains come from the appropriately named Coso Formation, which

is upper Miocene to upper Pliocene in geologic age, dated with

considerable radiometric confidence at 6.0 to 3.0 years old.

And all fossil specimens described from the Coso Formation derive

from a restricted sequence some 4.8 to 3.0 million years old.

This means that statigraphically speaking the Coso mineralized

skeletal material falls within the range of what vertebrate paleontologists

call the Blancan Stage of North American Land Mammal Age chronology--that

is to say, a geologic interval roughly 4.75 to 1.80 million years

ago. Indeed, the Pliocene Coso Formation yields up one of the

premiere Blancan Stage mammal localities in all the US West.

Petrological analysis demonstrates that the Coso hydrologic-volcanic

system deposited a composite aggregate of roughly 500 feet of

arkosic sandstones, shales, claystones, diatomite (a variety

of rock composed almost entirely of diatoms, a photosynthesizing

microscopic single celled algae), air fall volcanic ash, and

basalts in a relatively localized lacustrine (lake) basin influenced

by subordinate fluviatile (stream) and alluvial conditions that

contributed substantial detrital constituents to the continuously

operating three million-year regime of sedimentary-igneous accumulations--all

subjected on occasion to geophysically stressful extensional

(pulling apart of a portion of the earth's crust) and block-faulting

forces.

Significantly, near the conclusion of its depositional

history--between four and three million years ago--the Coso Formation

starts to record a dramatic influx of clastic-detrital debris

now eroding with sudden onslaught from a fault-controlled uplift

and eastward rotational tilting of the eastern front of the central

to southern Sierra Nevada--a still-active and fully on-going

creative geologic process that continues to fashion the great

elevations and breathtaking contrasts in topographic relief so

spectacularly characteristic of the eastern face of the Sierra

Nevada; the northern Sierra of course has stood at approximately

the same height as present since at least the early middle Eocene

Epoch some 48 million years ago, while the central to southern

Sierran area has been substantially uplifted during the past

five million years.

Geologist J. R. Schultz was the first scientist to investigate

this fossil fauna. He led experienced field technicians from

the California Institute of Technology on two extensive expeditions

to the Cosos, the first in the winter of 1930-'31, then another

during the summer of 1936. Schultz eventually published his geological

and paleontological findings in: Schultz,

J. R., 1937, A late Cenozoic vertebrate fauna from the Coso

Mountains, Inyo County, California, Carnegie Institute of

Washington Publication 487, pages 75-109. Among his many

fossil mammal descriptions were meadow mice, rabbits, haenoid

dogs, very large grazing horses--one of which was eventually

recognized by paleontologists as the world-famous Hagerman Horse

(one of the oldest members of the genus Equus, which includes

all modern horses and other equids)--peccaries, slender camelids,

and a short-jawed mastodon. Additional Coso Formation fossil

material, secured by teams of professional paleontology explorers

who succeeded Schultz's ground-breaking investigations, includes

undescribed ostracods (a minute bivalved crustacean), algal bodies

(stromatolitic developments created by species of blue-green

algae), diatoms (a microscopic single-celled photosynthesizing

single-celled algae), fish, a vole (the famous Cosomys primus,

named in honor of its occurrence in the Coso Mountains), a large-headed

llama, a bear--and, prolific quantities of pollen, palynological

specimens that add invaluable paleobotanical information to the

Coso story.

The Pliocene Coso Formation pollens come from what paleobotanists

call the Haiwee Florule, situated near the shores of Haiwee Reservoir

approximately five miles south of the Coso Range vertebrate fossil

locality. They were recovered from brownish siltstones in the

lower portions of the Coso Formation by the late paleobotanist

Daniel I. Axelrod and W. S. Ting through sophisticated--and extraordinarily

dangerous--laboratory procedures, involving the use of perhaps

the most potent/unforgiving acid known to exist, hydrofluoric

acid, whose efficient destructive activity on human tissue is

so rapid and overwhelming that permanent damage to epidermis,

muscles, and nerves occurs before one even feels any degree of

discomfort or pain after skin exposure. Published documentation

of that palynological study can be found in the scientific paper,

Late Pliocene Floras East of the Sierra Nevada, by D.

I. Axelrod and W. S. Ting, University of California Publications

in Geological Sciences volume 39, number 1, issued November 7.

1960.

The extensive fossil flora that Axelrod and Ting collaboratively

examined from the Pliocene Coso Formation includes such conifers

as: Incense Cedar; White Fir; Grand Fir; California Red Fir;

Bristlecone Pine; Jeffrey Pine; Sugar Pine; Singleleaf Pinyon

Pine; Western White Pine; Lodgepole Pine; Ponderosa Pine; Douglas-Fir;

Western Hemlock; and Giant Sequoia--in addition to the following

angiosperms: White Alder; Water Birch; Hazelnut; Blue Elderberry;

Pacific Dogwood; California Black Oak; Interior Live Oak; Silk

Tassel Bush; Black Walnut; Bush Poppy; Snow Bush; Deer Brush;

June Berry; Rock Siraea; Thimbleberry; Coyote Willow; Pacific

Willow; White Squaw Current; Red Prickly Currant; Kellog Sierran

Currant; Sierra Gooseberry; California Slippery Elm; and Zelkova.

Axelrod and Ting concluded that the overall paleo-environmental

aspect of the Coso Formation Haiwee Flora most closely resembles

today's Sierran pine-fir forests along the moist western slopes

of California's Sierra Nevada. Based on the known annual precipitation

totals necessary to sustain modern examples of such luxuriant

forest vegetation found in the fossil flora, Coso Pliocene times

experienced an estimated minimum of 35 inches of rain per year--whereas

today the area lies within what geographers categorize as the

Mojave Desert-Great Basin transition zone, which in the vicinity

of the Coso fossil occurrences receives a scant three to five

inches of rain per year, with soaring summer temperatures that

frequently exceed 110 degrees Fahrenheit; in forested Sierran

regions where modern-day members of the fossil flora now grow,

temperature rarely exceed 85 degrees F.

While fossil pollens lie preserved in older horizons of

the Coso Formation, all the vertebrate remains occur within a

rather narrow zone in the upper part of the Coso sedimentary

deposits; they are found in a buff-colored arkosic (composed

primarily of the mineral feldspar) sandstone which weathers into

subangular chunks. Often, the mineralized mammalian material

can be found already weathered out of the sandstone and in the

softer claystone a few feet below the sandstone. The fossil-bearing

horizon shows up within most of Pliocene exposures of the Coso

Formation, so there is a lot of territory to explore. Schultz's

original bone localities lie about two and a half miles from

State Route 190; reaching them now involves strenuous hiking

through rugged, desolate desert terrain. "In the old days,"

though, one could negotiate a four-wheel drive vehicle up a system

of packed sand desert washes, through magnificent outcrops of

the bone-bearing Coso Formation, to within a quarter mile or

so of the Schultz fossil quarry. As a matter of fact, with the

aid of "trusty" CJ5 and CJ7 jeeps, I managed to thread

my way back to the familiar box canyon parking spot several memorable

times before the Coso Range became a protected wilderness region--a

federally mandated designation which means, naturally, that without

a special BLM permit you can't keep anything you find there (paleontological,

or otherwise)--except in a camera.

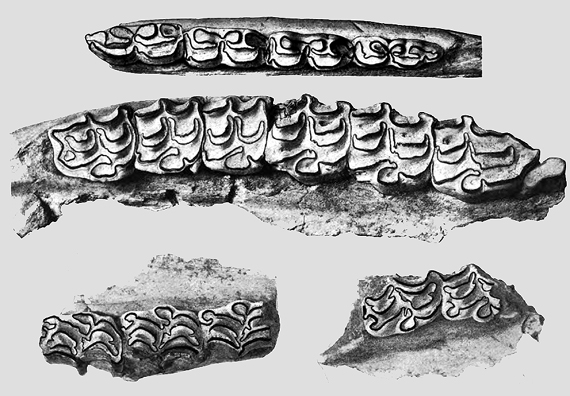

Although many Coso bones observed in surface exposures

will be fragmental, that doesn't necessary indicate that what

you've found can't be identified, eventually. In addition to

occasionally encountering isolated-scattered occurrences of complete

teeth and associated jaws, watch out, too, for such ostensibly

insignificant specimens as fractured limb sections and other

assorted incomplete post cranial skeletal elements that reveal

a crucially preserved articulating surface (a ball or socket

joint, for example). These are prize finds, indeed, paleontologically

speaking, as experts in vertebrate paleontology should be able

to determine exactly what kind of animal they came from. There

are certainly a good many fossil bones waiting to be found and

subsequently photographed where they reside in situ in their

sandy to clay-rich sedimentary environment. Probably the most

efficiently productive method is to locate the fossil-bearing

bed (it will tilt with the moderate dip of the sedimentary rocks,

and often it occurs on a precipitous hill-slope--so be careful),

then hike it out for as long as it is traceable. Some extensions

of the bone horizon are quite prolific, while others seem pretty

much barren.

All the way around, this is a great area in which to get

some exercise.

Though not necessarily during summer times, one must observe

with at least a modicum of sagacious deference to the months

of June through September in this part of the Northern Hemisphere,

when daytime temperatures regularly exceed 105 degrees. More

comfortable--and physically safer--hiking weather in this geographical

transition zone between the northwestern Mojave Desert and westernmost

Great Basin is traditionally encountered during mid to late Fall

and mid Spring.

Still and all--speaking of good old hot summertimes--I

must admit that my first acquaintance with the Coso bones was

during a particularly ultra-thermal early July. This was a number

of years ago, when I resided in coastal southern California.

This was a number of years ago, before the Coso Range became

off limits to off-road vehicles. This was a number of years ago,

before the Coso Range became the Coso Wilderness.

The preliminary circumstances: My father and I wanted to

escape the dismal, fog-bound coast of Santa Barbara. We wanted

to get out into the desert in the worst way possible. Thus, we

turned deaf ears to weather reports of 100-plus degrees on the

Mojave Desert.

Because when Coso paleo-urges strike...well, there's no

turning back.

At the crossroads in Olancha, at a filling station, somebody

was talking about 108 in the shade. That somebody was assessing

the conservative side of the situation. I was inhaling fire,

it seemed. Somebody else, the service attendant, would only shake

his head when I pointed, with what could have easily been interpreted

as braggadocious indifference to the brutal elements and the

imminent dangers they could present, down the road in the direction

of Death Valley in reply to his inquiry as to our destination.

At what our maps indicated was the correct intersection

of State Route 190 with a dry wash a number of miles beyond Olancha,

I idled the CJ5 jeep. No matter that the heat from the engine

overpowered the stifling furnace of the Mojave. We re-checked

our maps; and then decided to take yet another look at them.

This was the place all right, and the wash leading off into the

Coso Mountains invited us onward; not to mention the obvious

that the potential bone bonanza up ahead was a prime motivator.

I got the jeep down in the middle of the wash with the four-wheel

drive already engaged, primed for any kind of sandiness we might

encounter.

We should have been so lucky as to get stuck in some mere

sand.

What happened--and that within sight of the bone-bearing

badlands we had traveled some 250 miles to explore--was somewhat

more than we had expected. Smoke on a sudden came billowing from

beneath the hood, and the nauseating pungence of electrical wires

on fire became intense; this, just before the jeep jerked to

a halt, cold. We leaped to the situation with canteens in hand,

flipping open the hood to already charred remains of wires--and

we doused what we could. Then I ran with hectic unsteadiness

back to the rear of the jeep where we kept our extra water supply.

The five gallon container felt like a bag full of air as I plunged

its contents to the flames, dousing them repeatedly until only

sickening smoldering remained.

So what did we do next? Consternate? Curse? Nope, we took

a hike (fossil mania has its prerogatives). Just up ahead a few

hundred feet began the badlands exposures of the Coso Formation.

And it was with not a little anticipation that we struck out

to them with our remaining full canteens, leaving behind for

the moment that dead-in-the sand jeep. We crisscrossed those

ancient rocks while following the bone-bearing bed, and the paleontological

zeal propelled us further in that glaring, brutal heat than I

could have possibly foreseen.

But broken down jeeps wait for every man. A sobering mechanical

analysis of the predicament proved that the wiring had been fried

to a crisp when the horn mechanism had jarred loose, shorting

out the system: too many bumpy roads too many times taken. Aided

and abetted by the recollection of some basic electrical knowledge

garnered from a recent workshop (studying diagrams and such from

the jeep's manual from the curbside at home), we figured pretty

quickly that we could safely bypass the obvious tactic of securing

assistance when stuck out in the boondocks all alone, where nobody

in the world who knows where you are is there to lend a hand--in

other words, yelling and yelling like crazy at the top of your

lungs. No, this was too easy.

We chose to resort to a plan of action which in theory

we had only heard about; this entailed an electrical trick usually

quite controversial, but one worth trying under the circumstances.

It was decided that if we were ever to get out of that wash alive

we would have to "hot wire" the contraption.

The prospects did not excite us much. What if an officer

of the law should wander by and catch us in the hot wiring act?

Perish the thought! Yet, we persisted and pursued and made it

back to tell the tale.

And the moral of this story? Don't toot your horn too often

about how you can brave the desert elements, I suppose.

We maneuvered the jeep back to Santa Barbara the same way

it got to the Cosos to begin with--towed behind an Open Road

camper/RV, and later on down the line (with some creative electrical

finagling) we finally got a brand new wiring harness installed,

and the four wheel drive "contraption" was by all indications

good as new, and good to go: A new-and-improved jeep that actually

managed to survive numerous additional deep desert backroad adventures.

To all who visit the Coso badlands, don't be surprised

if someday you happen to spot a four-wheel drive vehicle stranded

along State Route 190, hood raised, the driver nowhere to be

seen. If this is the case, simply follow the boot prints in the

sand up a dry desert wash into the Cosos until you come upon

a fossil hunter, nose bent to the ground, examining a 4.8 to

3.0 million year-old mammal bone.

|