| Text: The Field Trip | Images: On-Site | Images: Fossils | Wigdet: Keeler Weather |

| Links: My Music | Links: My Fossils Pages | Links: USGS Papers | Email Address |

| The view from the crest of California's Inyo Mountains, near the Upper Mississippian Chainman Shale ammonoid locality, includes spectacular panoramas of the Sierra Nevada. Mount Whitney, the highest point in the contiguous United States at 14,495', is the peak just left of center along the Sierran skyline--a small white cloud touches its tip. Strata in the foreground include the Upper Mississippian Chainman Shale, which yields many species of ammonoids and pelecypods, in addition to terrestrial plants and even shark teeth at a unique fossil locality that lies in the vicinity of the old ghost town of Cerro Gordo, Inyo County, California. |

|

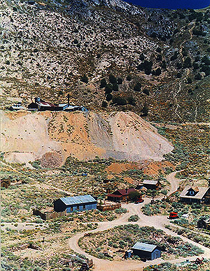

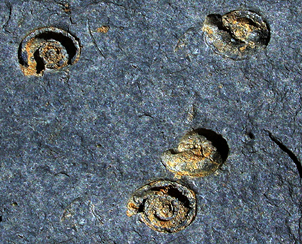

An unusual fossil locality occurs east of Owens Lake, near the crest of California's Inyo Mountains--a place many fossil enthusiasts call the Chainman Shale site, where 325-million-year-old ammonoids can be found along the same bedding planes that yield fossil shark teeth and terrestrial plants. The paleontological remains have been preserved in what geologists refer to as the Upper Mississippian Chainman Shale, a thick marine deposit, almost everywhere slightly metamorphosed--a geographically widespread rock unit (its type locality is over in eastern Nevada) that also contains several species of pelecypods and brachiopods, in addition to a peculiar orthocone nautiloid cephalopod called Bactrites, or in more colloquial language the "darning needle" cephalopod because of its sharply elongated, needle-like appearance in the rocks. The Inyo Mountains fossil horizon lies in the vicinity of Cerro Gordo, an abandoned mining camp that produced beaucoup spondulix worth of silver, lead, and zinc during the latter half of the 1800s (that would be many millions of dollars). It is now a picturesque ghost town preserved in what is euphemistically termed a state of "arrested decay." Years ago, before the question of legal ownership of the property had been settled, the multi-hued pulverulent mine tailings surrounding the town used to furnish collectors with such relatively uncommon mineral varieties as caledonite (a copper-lead sulfate), linarite (lead-copper sulfate), and leadhillite (a lead-sulfate-carbonate), in addition to excellent examples of smithsonite (a zinc carbonate) that often rivaled specimens from the famous Kelly Mine in New Mexico. But those days are now a distant memory in the minds of older mineral enthusiasts. Today, every last square inch of Cerro Gordo is privately owned, and mineral collecting within its posted boundaries is strictly forbidden without the owners' prior approval. For details about how to secure a permit to collect mineral specimens at Cerro Gordo, contact the regional office of the Bureau of Land Management in Ridgecrest, California. In the past, though, only "fully accredited individuals" have had success in finagling the essential legal documentation. Not only is the Cerro Gordo fossil district a productive and scenic area to explore, it is also a place of great paleontological importance. As one of only three known Carboniferous (the European equivalent of the Mississippian and Pennsylvanian Periods combined) ammonoid localities in all of California, it is also the only such example currently accessible to amateur fossil buffs. The other two occur in Death Valley National Park (officially established in 1994), near the famous Racetrack in the northern sector of the vast park--now, with the assimilation of many thousands of acres of adjacent wilderness lands, larger than the entire state of Connecticut--where rocks of varying shapes and sizes apparently slide in mysterious secrecy across a wide desert playa. The long-held traditional explanation was that during winter, with nobody around to see the phenomena occur, preferably in the dead of night, fierce wind gusts--upwards of 100 miles per hour--pushed the rocks across slippery playa muds saturated by rare episodes of Death Valley precipitation; a "definitive" explanation, though, is that on occasion ice sheets form around the Racetrack stones, creating minature "rafts" that proceed to transport the rocks across the wet playa when bumped by a neighboring ice sheet whose motion in turn is initiated by gusts of wind. In actual fact, both Death Valley sites are extensions of a single phenomenally productive cephalopod-bearing horizon in the Upper Mississippian Perdido Formation. Each yields innumerable ammonoids that characteristically weather out whole and intact, although many of the cephalopodic remains reveal obvious signs of degradation to their exteriors caused by the ceaseless abrasive weathering in the harsh transitional Mojave Desert-Great Basin Desert elements. Even so, numerous specimens still retain their original suture lines--that is, the distinctive growth line of the junction of a cephalopod's shell with the inner surface of its shell wall, which paleontologists use to identify the genus and species of all shell-bearing cephalopods, both living and extinct. Even though the Cerro Gordo locality fails to yield free-weathering specimens, its ammonoids and associated brachiopods, pelecypods, terrestrial plants and shark teeth are, nevertheless, common to abundant in the slightly metamorphosed detrital deposits of the Upper Mississippian Chainman Shale. They are preserved as attractive reddish-brown limonitic casts and molds of the original 325-million-year-old organisms, set on a matrix of pale-to medium-gray slaty shale. The majority of ammonoid specimens are rather diminutive, with diameters of generally 10 millimeters or less. So, be sure to carry with you a good-quality magnifying glass. Their preservation is fair to excellent--very surprising when you consider the degree of metamorphism the matrix was unavoidably subjected to in the geologic past. When the Sierra Nevada began to buckle upward during the late Jurassic Period, many relatively incompetent shale beds in the Inyo Range underwent moderate to severe alteration. That the ammonoids and associated goodies in the Chainman Shale escaped this ravaging assault was indeed a miraculous occurrence. Prior to their having survived obliteration by powerful geologic processes, the Chainman Shale organisms were deposited at the muddy bottom of a rather deep, warm-water Paleozoic sea some 325 million years ago. Now they lie at elevations of 8,800 to 9,000 feet near the crest of the great Inyo Range near Cerro Gordo ghost town. The ride up to the site, along the precipitous western flanks of the Inyo Range, is a hair-raising adventure. The jeep trail climbs over a mile in a mere seven or eight miles...although the vast majority of that amazing ascent takes place within a distance of only three or four miles. Needless to say, only those with a reliable four-wheel-drive vehicle should consider accepting the challenge. It doesn't hurt to be in at least moderate physical condition, either. Once within striking distance of the fossil ammonoids and shark teeth, you will have to hike at elevations approaching 9,000 feet. For those unaccustomed to exertion at high altitudes, serious consequences can result--not the least of which is altitude sickness, a debilitating condition caused by prolonged oxygen depravation. The turnoff to the Chainman Shale fossil bonanza lies along the eastern side of Owens Lake--an essentially dry saline depression most of the year (occasional heavy runoff from the mountains during Spring sometimes results in a big shallow pond that evaporates quickly)--near Keeler, where Cerro Gordo Road intersects State Route 136 13.5 miles southeast of Highway 395. Check your pulse at this point and get a grip! The adventure begins at a modest 3,800 feet or so, with billows of irritating saline dust rising from "Owens Lake." Within just a few miles (when hairpin turns spiral upward and upward), you might reconsider having stayed behind in what had previously seemed the inhospitable Owens Lake below, and even find yourself obsessing on the flatness of it--that wonderful level expanse with no sheer drop-offs on either side. Turn east on Cerro Gordo Road. Here you leave civilization behind. You will be striking though a great wilderness: a geological wonderland comprised of thick geologic rock deposits, in which many kinds of Paleozoic Era fossil remains can be recovered. Mainly these include fusulinids, brachiopods, corals, bryozoans, and crinoid fragments from the middle Pennsylvanian Keeler Canyon Formation and the Lower Permian Owens Valley Group. Also exposed in the area surrounding Cerro Gordo is the Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone (350 million years old)--a noted producer of corals and crinoids in particular from massive reef-like carbonate accumulations in its youngest phases of sedimentary deposition. During the first 2.2 miles of four-wheel drive travel, you pass through Pleistocene (present official calibration--2,588,000 to 11,700 years ago) to recent fanglomerate--extensive accumulations of eroded debris from every sedimentary and volcanic outcrop in the Inyo Mountains. Limestone cobbles in the alluvial material sometimes contain abundant fusulinid tests; however, because the host deposit consists of weathered rock out of its normal stratigraphic position, the best that can be said regarding its geologic age is that any fusulinid found within it probably came from either the Keeler Canyon Formation or the Owens Valley Group. These are the only rock units in the Inyo complex known to contain the distinctive wheat-shaped test secreted by an extinct single-celled animal. At 2.2 miles from State Route 136, Cerro Gordo Road begins to slice through the Lower Permian Owens Valley Group, which is roughly 285 million years old. Here, the Owens Valley is composed of several sedimentary lithologies, including silty fusulinid-bearing limestone, lenticular organic limestone (within which brachiopods, corals, crinoids and bryozoans can be found), calcareous shales, sandy limestone, limestone-mud breccias, and relatively pure limestones. Fossil remains are not abundant in the Owens Valley exposures along Cerro Gordo Road. But farther southeast, in the Darwin District of Inyo County, profuse fusulinids, brachiopods, and corals have been reported. For 1.4 miles Cerro Gordo Road passes through dramatic exposures of the Lower Permian Owens Valley Group. Then it intersects an unnamed terrestrial accumulation of Middle Triassic (220 million-year-old) volcanics and sedimentary rocks approximately 2,200 feet thick. The volcanic facies includes andesite flows, breccia and tuffs of gray, red and purple; among the sedimentary constituents are shale-sandstones and conglomerates of gray, red, green and purple. None of the land-laid Triassic exposures is fossiliferous, though. After cutting through the thick Middle Triassic terrestrial sequence for 1.5 miles, Cerro Gordo Road penetrates the marine Lower Triassic Union Wash Formation (roughly 235 million years old), some 1,800 feet thick. Unlike its classic fossil-rich outcrops in Union Wash northeast of Lone Pine, the exposures along Cerro Gordo Road bear only rare, fragmental ammonoids representing the genus Ussuria. The cephalopods occur in brownish-gray, silty limestones some 50 feet thick, along with abundant minute gastropod molds and infrequent pelecypodal lenses. The Union Wash Formation is wonderfully exposed for 0.8 mile, forming craggy reef-like ridges and colorful slopes composed of thin-bedded shales in hues of pale greenish-gray, light gray, yellowish-orange, and slightly greenish-yellow. At a point 5.9 miles from State Route 136, Cerro Gordo Road intersects the Middle Pennsylvanian Keeler Canyon Formation (roughly 310 million years old). It's approximately 2,200 feet thick, a predominantly carbonate-shale sequence in which the arenaceous to argillaceous limestones often yield crinoid material and abundant tiny fusulinids that for the most part are only moderately well preserved. Typically, the shale interbeds are totally barren of paleontology--yet, from a perspective of casual inspection they seem so inviting, appearing eminently suitable for the preservation of many varieties of Paleozoic organisms. Persistent investigations of them may eventually reveal something truly remarkable. For the next 1.1 miles, the Keeler Canyon Formation outcrops in prominent fashion along both sides of the road, affording easily accessible exposures for fossil explorations. Abundant small fusulinids and occasional disarticulated crinoid stems occur at irregular intervals throughout the carbonate sequence. At a point 7.0 miles from State Route 136, the Middle Pennslyvanian strata rest in a prominent fault contact against the older Upper Mississippian Chainman Shale (about 325 million years old). The first Chainman outcrops encountered consist of smooth slopes underlain by dark gray to black carbonaceous shale and blocky-weathering argillite (a heat-and-pressure-altered clay shale), with subordinate interbeds of fine-grained sandstone and limestone. Periodic roadcuts during the next 1.3 miles--all the way up the remainder of the grade to Cerro Gordo Summit--reveal unfossiliferous brownish-red to dark gray argillites and characteristic thin-bedded, often cleavable black shales. The fabulous Paleozoic Era fossils occur in grayish-black, slightly fissile shales of the Upper Mississippian Chainman Shale at a lone, isolated locality which lies in the vicinity of Cerro Gordo Summit; even though fossil specimens are quite common at the specific site, preserved through roughly 50 feet of well exposed strata, collectors will still have to watch carefully for the invariably small ammonoid casts and molds. On the other hand, common fragments of mature specimens demonstrate that the largest varieties here could grow to approximately 60 millimeters across (two and a half inches). The most abundant ammonoid represented at the Chainman Shale site is Cravenoceratoides nitiloides, a type originally described from a locality near Yorkshire, England. Less commonly observed species of ammonoids include Cravenoceras nevadense, Cravenoceras richardsonianum, and Eumorphoceras bisulcatum. A second variety of cephalopod occasionally encountered is Bactrites, referred to in scientific terms as an orthocone nautiloid cephalopod. Bactrites is in reality more closely related to the modern chambered nautilus than are the extinct ammonoids and ammonites, whose coiled morphologic aspect bear only a superficial resemblance. Paleontologists identify cephalopodic affinity not by the rough similarity of exterior shell designs but, rather, by the unique suture signature they happen to bear. Based on their distinctive suture patterns, all ammonoids and ammonites can be classified into three separate orders: goniatitic (species with nonserrated sutures, generally considered the most primitive varieties)--the kind found in the Chainman Shale; ceratitic (sutures with serrated lobes); and ammonitic (very complex suturing--usually referred to as the most advanced order of ammonites--and the only order that can properly be termed an ammonite; the goniatitic and ceratitic types are necessarily called ammonoids). The goniatites first appear in the geologic record during the Devonian Period, some 370 million years ago; they persisted all the way up to the great dying at the conclusion of the Permian Period (when trilobites finally disappeared, as well), 252 million years ago. During the Permian Period both ammonoid and the ammonite varieties became common. But by Triassic times (252 to 201 million years ago), only the ceratitic forms proved particularly successful. Then they, too, died out at the conclusion of that geologic period, leaving only the ammonitic types, the ammonites proper, to carry on the cephalopodic heritage. Throughout the Jurassic Period (201 to 145 million years ago) ammonitic ammonites thrived, becoming increasingly complex and numerous in the oceans of the Mesozoic world. They persisted right up to the close of the Cretaceous Period (66 million years ago), becoming extinct along with all the sensational terrestrial giants of that age--the dinosaur. In addition to the cephalopods, the molluscan class Pelecypoda (or, Bivalvia--the bivalves--of more modern malacological terminology; an older designation was Lamellibranchia) is well represented in the Chainman exposures. The pelecypods here are typically much larger finds, easily spotted as reddish-brown limonitic impressions and silvery sheens--original lustrous shell material may be present some instances--on the darker grayish shales. Two of the more common varieties present include Caneyella wapanachensis and Caneyella richardsoni, each of which is frequently found preserved intact with both valves splayed open along the hingeline. Not only are invertebrate fossils common in the Chainman outcrops, but fascinating fossil shark teeth can also be observed. For the most part, they occur as limonitic casts and molds, stained a pleasing reddish-brown on a grayish shale matrix, barely a few millimeters in length. One collector, though, has reported finding a three-quarters inch beauty with a distinctly serrated edge. Just what variety of shark they came from is anybody's guess, but it is quite exciting to come across an obvious tooth lying next to an ammonoid along the same bedding surface...a splendid fossil occurrence, indeed. Of course, prior to September 2022, gathering and keeping any kind of vertebrate fossil on Public Lands was usually considered verboten, forbidden, but most folks used to understand that collecting shark teeth--the vertebrate equivalent of a common invertebrate fossil such as a brachiopod or coral, for example--specimens one is permitted to keep on BLM administered territory--was not in the same category as removing, say, dinosaur remains, or even mammalian skeletal elements from Public Lands, an activity that is universally not allowed since such specimens are considered "rare" and of vital importance to the scientific community. Not any longer, though. New federal fossil collecting regulations became effective on September 1, 2022. According the US Department of The Interior, fossil shark teeth will no longer be considered a common fossil, comparable with common invertebrate and plant fossil material that folks can collect on BLM-administered lands (AKA, public lands) without a special permit. Beginning September 1, 2022, collecting fossil shark teeth on public lands (Bureau of Land Management/BLM) became illegal without a special permit issued solely to individuals with a minimum B.S. degree whose formal scientific research projects can be verified as authentic by the petitioned authorities. Also present in the carbonaceous shales are common to abundant poorly preserved terrestrial plants, most of which were likely derived from a nearby coal-swamp paleoenvironment. The most readily recognizable forms resemble slender algal structures preserved as faint fragmentary outlines of vermiform configuration. The second group consists of branching stems and flat, straight impressions of rushes and ferns. Lying directly above the fossiliferous grayish shales is an inconspicuous three-foot layer of silty limestone. Most often, a thick talus overburden of weathered shales masks its presence, but careful inspection of the narrow horizon usually discloses a wonderful variety of Paleozoic invertebrate remains--including the corals Triplophyllites and Chaetetes; a fenestellid bryozoan; a trilobite (Proetus missouriensis); a gastropod (Pleurotomaria brazeriana); and the following brachiopods: Spirifer (two species), Composita lewisensis, Productus (two species), Diaphragmus elegans, and Dictyoclostus sp. Such brachiopods, bryozoans and corals all add dramatically to the sensational plethora and variety of fossil specimens that can be recovered from the Chainman Shale locality, situated in the transitional northernmost Mojave Desert-westernmost Great Basin Desert along the crest of eastern California's Inyo Mountains, in the vicinity of Cerro Gordo ghost town. While today's fossil specimens lie at an altitude of roughly 9,000 feet, during Late Mississippian geologic times they would have been buried perhaps thousands of feet below sea level by detritus eroded away from already long-vanished mountains. Now, in the rarefied atmosphere of the high Inyo Mountains, fossil collectors become deep-sea divers of the Paleozoic Era, plunging far below the surface of the eons to explore layers of lithified muddy ooze, to search for ancient animal life that once took in oxygen from many fathoms below Earth's surface of the ocean some 325 million years ago. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right--The view is eastward from Cerro Gordo Summit in the Inyo Mountains, California, near the intersection of Cerro Gordo Road and Swansea-Cerro Gordo Road, 8.3 miles from State Route 136. Elevation is nearly 9,000 feet; the steep slopes at extreme right of picture are composed of the Middle to Upper Devonian Lost Burro Formation, which locally yields profuse stromatoporoids (an unusual variety of sponge), brachiopods, crinoids and gastropods. The distant mountains all lie within Death Valley National Park, established in December of 1994. Right--The drive up to Cerro Gordo Summit along Cerro Gordo Road affords spectacular vistas; reddish-brown strata in foreground consist of the Upper Mississippian Chainman Shale. The view is west across Owens Valley to the Sierra Nevada. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right--The "Narrows" along Cerro Gordo Grade--here, Cerro Gordo Road slices through an unnamed Middle Triassic terrestrial formation conisting of volcanic tuffs and breccias; four-wheel-drive is mighty handy to help negotiate the steep ascent and variable quality of the dirt trail; seen here a 1959 Willys jeep--complete with winch, gas carrier, water carrier, tow bar, and even a rack. Right--A view roughly southeast along Cerro Gordo Road to a long-abandoned tramway that served the Cerro Gordo mining district during its boom years (probably late 1800s to early 1900s). Reddish brown, stratified rocks in middle ground belong to the Middle Pennsylvanian Keeler Canyon Formation, which yields abundant fusulinids and crinoidal debris; bluish-gray, cliff-forming strata near skyline, in distance, are composed of the Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone; rocks lower on the mountain side (underlying the more slope-forming, hilly terrain) belong to the Middle to Upper Devonian Lost Burro Formation. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right--The view is roughly south to a portion of Cerro Gordo Ghost town. Dark bluish rocks in the distance, along skyline, belong to the Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone, which locally yield abundant corals, brachiopods, and large crinoid stems; whitish-pale gray strata along lower slopes consist of dolomites in the Middle to Upper Devonian Lost Burro Formation. Right--A seeker of Paleozoic paleomtology investigates the prime fossil locality in the Upper Mississippian Chainman Shale, as exposed in the vicinity of Cerro Gordo ghost town near the crest of the Inyo Mountains. Ammonoids, orthocone nautiloid cephalopods, pelecypods, shark teeth, and even fragments of terrestrial plants occur in a 50-foot section of dark gray to black, commonly fissile, slighly metamorphosed shale; bluish-gray rocks at upper left of picture, just below the blue sky, belong to the Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right--Here's a pelecypod specimen, genus Caneyella, from the Upper Mississippian Chainman Shale, collected in the vicinity of Cerro Gordo. Notice how both valves have been preserved, splayed open along the hinge-line on the slightly metamorphosed 325-million-year-old chunk of shale; combined, both valves together measure 28 millimeters in diameter. Right--Here is an orthocone nautiloid cephalopod, genus Bactrites from the Upper Mississippian Chainman Shale, collected in the vicinity of Cerro Gordo ghost town; actual size of specimen is roughly 18mm long. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right--Ammonoids called scientifically Cravenoceratoides nitiloides (12 millimeters in actual diameter) on a slab of slightly metamorphosed shale from the Upper Mississippian Chainman Shale, Inyo Mountains, California. Right--A pelecypod, with both valves preserved splayed open along the hingeline, from the Upper Mississippian Chainman in the vicinity of Cerro Gordo Ghost Town, Inyo Mountains, California. Caneyella sp., 27 millimeters long in actual dimension. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left to right--A pelecypod from the Upper Mississippian Chainman Shale in the vicinity of Cerro Gordo ghost town, Inyo Moungains, California. The specimen is Caneyella sp., 25 millimeters in actual length. Right--A shark tooth, species unidentified, from the Upper Mississippian Chainman Shale in the vicinity of Cerro Gordo ghost town, Inyo County, California. The specimen is 8 millimeters long. |

|